Though the brightly-hued cover photo affixed to this edition of Simon Raven’s second published novel ‘Brother Cain’ carries a distinct whiff of pop-art / psychedelic chic, Panther’s paperback was actually printed in February ’65, too early to have really hitched a ride on the ‘swinging sixties’ bandwagon, whilst the book itself was first published back in the grey, buttoned up world of 1959.

One of those renowned-in-their-day-but-now-largely-forgotten authors whose work always sparks a certain fascination, Simon Raven (1927-2001 - and yes, that was indeed his birth name) wrote voluminously through much of the latter half of the 20th century, and, read today, his books feel both strikingly modern (in terms of their frank and non-judgemental approach to sexuality and general air of shark-ish cynicism) and hopelessly old fashioned (being largely concerned with a segment of upper crust British society whose values and behaviours now seem entirely alien, probably even to those lucky enough to have been born into it).

Freely mixing elements of personal / social writing and thinly veiled autobiography into popular genre thrillers, Raven’s more noteworthy works include Oxbridge vampire yarn ‘Doctors Wear Scarlet’ (loosely adapted into Robert Hartford Davis’s disastrous Incense for the Damned in 1971) and, on the other side of the coin, the ten volume ‘Alms for Oblivion’ sequence, which follows the lives and loves of a cadre of toffs, set against the changing social and political mores of post-war England. (I read the first few chapters of the first volume of this epic saga a few years back and actually found it quite compelling, but unfortunately I lost my copy on a train and haven’t got around to picking it up again since.)

Throughout his early literary career, Raven seems to have been fixated on the dilemmas faced by male scions of the English upper classes who, whether through conscious rebellion or mere lethargy and personal weakness, have squandered the privileges conferred to them by their noble upbringing and must find alternative paths through life. This theme is certainly front and centre in ‘Brother Cain’, whose protagonist Jacinth Crewe (note the Moorcock-ian initials) finds himself in a predicament closely mirroring that apparently faced by the author himself a few years beforehand.

Having been expelled from Eton on the grounds of moral turpitude and subsequently forced to curtail his studies at Cambridge due to what we might charitably call a self-inflicted lack of funds, the novel joins Crewe as he is invited to offer his resignation to the British army’s elite training academy at Sandhurst, having accrued gambling debts sufficiently gargantuan as to bring his entire regiment into disrepute.

“Honour and dishonour are conventions,” Captain Crewe’s understanding commanding officer advises him during their final interview, effectively establishing the theme of the novel to follow. “They are relevant in the world in which you have so far existed: they will not be relevant in the world for which it is clear you are now destined.”

Retreating to London with his tail (amongst other things) between his legs, Jacinth throws himself upon the mercy of his regiment’s allotted merry widow, one Miss Kitty Leighton, who, after a night or two of wild passion at her Chelsea flat, places a call to a mysterious contact who may be able to assist her disgraced and destitute young lover before the debt collectors come knocking.

Thus, Jacinth is summoned to a lunch date at the Trocadero in Piccadilly (decades before it became the tourist-choked hellhole we know it as today), where he is greeted by dirty mac-clad, brown ale supping “professional messenger” Mr Shannon - a character I found it impossible not to imagine being played by Donald Pleasance.

Though highly suspicious on all levels, the proposal Mr Shannon’s anonymous employers wish to convey to Captain Crewe is entirely too good for the desperate young layabout to resist. In short, his gambling debts will be covered in full, and he will be issued with sufficient funds to allow him to fly to Rome and install himself in the swank Hotel Hassler overlooking the Spanish Steps, there to await further instructions.

What with this being the height of the First Cold War and everything, you’ll be unsurprised to hear that when those orders do eventually arrive, they direct Jacinth to an appointment at a shabby ‘Institute for the Promotion of Mediterranean Art’, a flimsy front for a top secret wing of the British government whose job, to all intents and purposes, is to create new James Bonds.

Which is to say, Jacinth and the other young rascals corralled by the nameless ‘organisation’ are pointedly not being groomed as spies or intelligence agents. Instead, they are basically just hatchet men - proponents of what one of their instructors (who is of lower middle class extraction, and so naturally a graceless, grudge-bearing git) bluntly calls “the cold art of murder”.

Taking a more refined view on things, the Big Cheese of the whole operation, who naturally enjoys the benefit of a ‘proper’ education, instead waxes lyrical to his new recruits about how, in the light of communist infiltration and so forth, the democratic institutions so cherished by western nations can only be preserved through the unilateral execution of acts which the champions of democracy would find impossible to countenance, should they become aware of them.

(Being unfamiliar with Raven’s own political leanings, assuming he had any, it’s difficult to get a handle on whether this justification for extra-judicial murder and mayhem, which continues at some length, is being presented as satire, or simply as a statement of the author’s own beliefs.)

Furthering the Bond parallel, Jacinth and his fellow recruits are essentially allowed to adopt the lifestyles of globe-trotting playboys, so long as they follow their orders precisely, ask no questions, and leave whatever moral scruples they may once have possessed at the door. And, if they have any thoughts of ducking out and taking their chances in civilian life, well…. their more ruthless classmates will simply have an easy first assignment to look forward to, won’t they?

Despite his military rank, Jacinth Crewe is still more a feckless dosser than a cold-blooded killer, and, still bedevilled by confused notions of personal honour and brotherly conduct, he is naturally terrified by the prospect of having to immerse himself in the paranoid, compassionless world promised by his new profession - all the more so when, with a neatness which surely defies mere coincidence, he is paired up for training with one Nicholas Le Soir, the former schoolmate whose charms led to his being expelled from Eton for corrupting the morals of a younger boy. (This incident directly mirrors Raven’s real life expulsion from Charterhouse public school, incidentally.)

Now a qualified surgeon, Le Soir has arrived at the ‘organisation’ after being struck off and effectively exiled from the UK for performing an illegal abortion upon the daughter of a prominent Catholic family (oops), and the plot is further thickened once both Jacinth and Nicholas find themselves drawn into an embryonic love triangle with Le Soir’s promiscuous yet sexually dysfunctional cousin Eurydice, who is also resident in Rome, working for an equally questionable ‘cultural mission’…. and who seems suspiciously keen on pumping her two mixed up suitors for information on the nature of their employment.

And, there I will leave my plot synopsis, but suffice to say, Raven proves himself eminently capable of setting up a fast-moving, exquisitely intriguing yarn here, even if his story’s conclusion - following an incident in a bat-infested railway tunnel, a scheme to virally infect the whores of a high class brothel and a head-spinningly convoluted murder scheme set against the backdrop of a Venetian masked ball, amongst other diversions - eventually veers more toward the kind of existential, internecine futility in which John le Carré would later specialise than the two-fisted action-adventure stuff beloved by Ian Fleming’s fans.

In view of the fact that ‘Brother Cain’ was first published a full decade before the legalisation of male homosexuality in the UK, one of the most striking aspects of the book for modern readers is Raven’s forthright and unapologetic presentation of his male characters’ bisexuality. Not only acknowledging this dark secret of the English public school system, which tended to be referred to only through implication and innuendo by other writers of this era, he seems keen on eagerly exploring its every nook and cranny, pushing the book’s language about as far as the era’s censorship would allow.

“I’m not a homosexual, or at least, not very often,” Jacinth muses to himself as he drifts into introspective reverie in the flight to Rome. (“What shall I do about women? Well I suppose there must be brothels..,” he charmingly adds, as if to bolster his own sense of masculinity.)

As soon as he falls asleep though, he finds himself dreaming of a beautiful American boy he once briefly courted at Cambridge (and who will, of course, play an integral role in the unfolding plot), and as the book goes on, it becomes increasingly clear that Jacinth’s most significant and long-lasting relationships have always been with other men.

In spite of its attention-grabbing plotline in fact, ‘Brother Cain’ often reads more like a semi-autobiographical personal novel than it does a thriller. More specifically, it seems like an attempt on Raven’s part to take stock of his life to date, and to redefine his place in the world as he hit his early 30s. As noted, the parallels between the background of the book’s protagonist and that of the author himself are considerable, and, given the multiple accusations of libel which were levelled against Raven as a result of his writing over the years, it wouldn’t be surprising to learn that many of the secondary characters in ‘Brother Cain’ were simply thinly veiled versions of his own friends, lovers and acquaintances.

Suffice to say, Raven was presumably not actually press-ganged into committing top secret outrages on behalf of the British crown, but, at a push, you could perhaps see Jacinth Crewe’s recruitment by the ‘organisation’ as a reflection of Raven’s own unique arrangement with the publisher Anthony Blond, who, when the author found himself in particularly dire straits, is reported to have agreed to pay him £15 a week in perpetuity and to publish his books as and when he completed them, on the understanding that he should leave London and never return.

Elsewhere, the book’s story is jammed with sinister, wisdom-dispensing potential father figures and unbalanced, mothering women, whilst Jacinth’s ruthless generational contemporaries all seem ready and willing to trample on his yearning, sensitive soul, creating a maelstrom of weird moral / psychological angst which can only really end with our protagonist becoming entirely consumed by it as he slips helplessly between the cracks separating the world of ‘honour and dishonour’ from the one in which most of us now live, in which such concepts are simply a quaint irrelevance.

Normally of course, I’d be pretty pissed off to find a book which has all the makings of a rip-roaring mid-century thriller derailed by such a load of ponderous navel-gazing, but Simon Raven was such a fascinating character, and the lost world of foppish decadence in which he dwelled such an enticing one to visit, that in his case, I’ll happily make an exception.

Whatever you may think about his conduct or way of life, Raven was a strange and unique literary talent; even at this early stage of his career, his prose and plotting are crisp, witty and ruthlessly efficient, and I’ll certainly be redoubling my quest for more of his work as soon as the doors of the world’s surviving second hand bookshops begin to creak open once again.

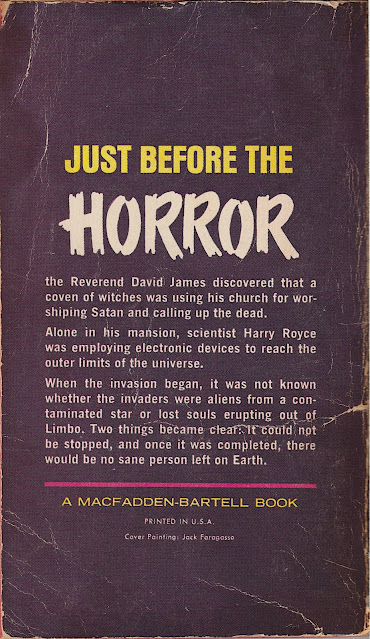

Another example of a ‘60s US sleaze paperback recently discovered on these shores - I scored this one at a car boot sale in Peckham, no less.

Another example of a ‘60s US sleaze paperback recently discovered on these shores - I scored this one at a car boot sale in Peckham, no less.