It’s been far too long since we last took a peek into the head-spinning world of Rialto Films’ series of West German Edgar Wallace adaptations, so what better way to get re-acquainted with their particular brand of ersatz-English weirdness than by screening 1961’s ‘The Green Archer’ (or ‘Der Grüne Bogenschütze’, as the Germans more poetically have it)?

This was the fourth entry in the series insofar as I can make out, released just one month prior to Alfred Vohrer’s definitive The Dead Eyes of London, and… it certainly gets off to a flying start.

Thunder crashes, and lightning splits a tree in the midst of a field of rain-lashed stock footage countryside overlooking an imposing gothic manor house. Immediately kicking a few bricks out of the ol’ fourth wall, series mascot / comic relief supremo Eddi Arent adjusts his regulation Stan Laurel-esque bowler and speaks straight to camera; “You couldn’t possibly make a movie out of this. Impossible!”

The scene, we gradually realise, is a dark and stormy night in Garre Castle, wherein elegantly attired secretary / caretaker Julius Savini (Harry Wüstenhagen, looking rather like a young Martin Landau) is conducting a public tour, apparently without the permission of his absent employer.

Arent’s characteristically eccentric reporter character (he works ‘for the newsreels’, and carries an antiquated box camera, despite this film being set in the early 1960s) is among the guests at this rare function, who, helpfully, are in the process of being briefed by Savini on the legend of The Green Archer - an emerald-hued avenger who is said to have fought against the house’s tyrannical medieval owners back in the 12th century, and whose spirit is now alleged to haunt the joint.

Quite why the aforementioned tyrannical owners chose to retain a statue of this irksome individual in their study is anyone’s guess, but… there ya go.

As the tour moves on, an elderly gentleman lingers, carefully examining the statue of the archer with an eyeglass. Shortly thereafter, the man turns up dead, with a bloody great green arrow sticking out of his back!

In true Krimi style, the other guests respond to this cold-blooded slaying with a mixture of amusement and mild annoyance, whilst a crash zoom brings us back into Arent’s confidence. “Yes, I think this will make a very nice movie,” he concludes.

Roll credits (featuring more rollickingly weird, Peter Thomas-esque music from the delightfully named Heinz Funk), and…. before we know it, we’re being haphazardly introduced to a bewildering multitude of loosely sketched out characters and sub-plots. Trying to keep track of what the hell is actually going on here in fact proves quite challenging, but, for the sake of this review, I’ll gird my loins and try to give it my best shot.

So, first of all, there’s this wealthy young man named John Wood (Heinz Weiss), who appears to have bought the abandoned building which sits opposite the gates to Garre Castle, with the intention of turning it into an orphanage. (“Bringing happiness to children is my greatest joy,” he exclaims, not at all suspiciously, shortly before we see his face reflected in a broken mirror.)

He is accompanied in this mission both by Valerie (the flawlessly beautiful Karin Dor), and by a silver-haired gent who appears to be her father, though the exact relationship between these three characters remains somewhat unclear. Valerie is apparently in desperate search of her biological mother, and believes (for reasons which also initially remain mysterious) that she can make progress in this direction by snooping around Garre Castle. As such, I suppose the implication must be that she is a former resident of one of the other orphanages administered by Weiss, and that the silver-haired fellow must be her adoptive father, but… who knows.

Anyway, Valerie also appears to be involved in secret tryst with one Mr LaMotte (top-billed Klausjürgen Wussow), whom we initially meet lurking around in a darkened room in her new home. It subsequently turns out though that he is actually a police inspector working undercover, and in this capacity he subsequently pops up, cunningly disguised behind a set of false whiskers, as a kind of handyman / wood carrier within the castle.

In doing so, he is replacing yet another ancillary character, an even shiftier, disgruntled handyman who some comes a-cropper, becoming the second latter-day victim of The Green Archer after inviting Arent’s reporter character back to his bungalow in, uh, Stanmore, apparently (hmm, someone’s been looking at the tube map, methinks) to dish the dirt on his employer.

This leads us on to the police contingent, sadly not headed up on this occasion not by everyone’s favourite playboy detective Joachim Fuchsberger or his principal Sir John, but by the rather more down-at-heel, fish-faced Inspector Higgins (Wolfgang Völz). He and his unequally unmemorable crew of underlings are of course soon all over Garre Castle like a rash, though they initially seem less intent on solving the attention-grabbing murder that has recently occurred there than they are on merely keeping tabs on the house’s errant and disreputable owner (of whom more later).

Meanwhile, there’s also this gargantuan, bald-headed fellow named ‘Coldharbour Smith’ knocking about. Resplendent in white suit and dark glasses, Coldharbour Smith (played by Stanislav Ledinek) runs “a disreputable nightclub down by the docks”, named ‘The Shanghai Bar’. (In a regrettably lazy touch, this more urban locale is introduced via stock footage of Piccadilly Circus - an area of London not notably close to any “docks”.)

Within the rather groovy, tiki-styled interior of the Shanghai Bar, we are introduced to an additional floozy (Edith Teichmann) whom, it transpires, is the wife of Julius Savini (you remember, the castle secretary guy), and who also appears to be somehow involved in… whatever the hell it is that may or may not be going on in or around Garre Castle.

Amidst this scattered and salty crew however, by far the most memorable character in the film turns out to be the aforementioned owner of the castle, Abel Bellamy (Gert Fröbe), who eventually arrives, disembarking from a flight at good ol’ London Airport, having apparently just spent some time over in the USA.

Indeed, although you wouldn’t necessarily know it from the German language track, Bellamy is meant to be FROM the USA, where he appears to made his name as a notorious, Al Capone-styled gangster who, for some reason, has bought himself a historic English manor house, where he wishes to live in privacy.

Fat chance of that however, as he is mobbed by a phalanx of reporters at the airport, firing questions at him about his unsavoury associations back in Chicago, and the murder which just took place on his property. A bullish and aggressive man whose Churchillian girth surpasses even that of Coldharbour Smith, Bellamy responds with rage, intimidation and violence - qualities which continue to define his interactions with pretty much everyone through the remainder of the movie.

Now, if you’re wondering how all of the above is able to coalesce into a coherent plotline, well… cards on the table, I haven’t the faintest idea. Simultaneously horrendously convoluted and hopelessly vague, Wolfgang Schnitzler and Wolfgang Menge’s adaptation of Wallace’s 1923 novel represents a singularly unsatisfactory example of the screenwriter’s art. (1)

In fact, by the time the thread of the narrative degenerates into a repetitive series of nocturnal creeping about, confinements and escapes during the latter half of the film, it’s probably best just to give up trying to figure things out, and just go with the flow.

After all, we have essentially got everything a Krimi fan could ask for at easy reach here. A creepy, ancient house full of labyrinthine corridors, complete with the inevitable secret passage leading down to a set of subterranean caverns; an over-stuffed cast of shifty, scheming oddballs; touches of urban modernity provided by nightclubs and gangsters; and, most importantly, some loon in a costume derived from a medieval spectre, running around murdering extraneous characters in a suitably outlandish manner.

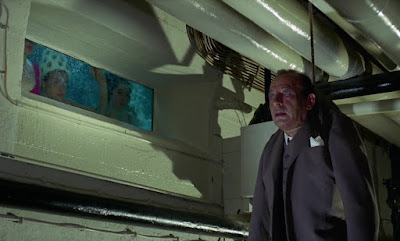

Jürgen Roland’s direction is… decent. Though he lacks the attention-grabbing eccentricity of Alfred Vohrer or the pulp kineticism of Harald Reinl, he nonetheless utilises some stylish framing here, revelling in the pleasures of cramped, chaotic, multi-layered compositions, perhaps mirroring the film’s tangled plotting. He rarely fails to arrange the all-too-numerous figures on-screen into interesting patterns anyway, throwing in plenty of nice, looming foreground objects and subtle, gliding camera moves to keep things lively whilst he’s at it.

He is greatly aided in this by both Heinz Hölscher’s top notch black and white photography, and Mathias Matthies & Ellen Schmidt’s splendid production design, which incorporates many of those neat little props and macabre oddities found in all the best Rialto Krimis. (The skull and crossbones flag appended to castle gates to warn of an electric fence, the arm of the archer statue serving as the secret passage lever and the scurvy stuffed monkey in the interior of the bar, provide just a few examples).

The cast do solid work too, on the whole. I found Arent a lot less annoying here than in some other films in the series (or, perhaps I’m just gradually warming up to his unique comic stylings, god help me). Dor meanwhile is absolutely radiant, and Frobe certainly makes an impression as perpetually furious Abel Bellamy (both he and Ledinek’s Coldharbour Smith prove great heavies).

It’s a shame then, that - as I may have already mentioned once or twice - the film’s egregious scripting deficiencies mean that none of these qualities ever quite gel together the way they should.

Despite providing a fair amount of ambient / aesthetic enjoyment, ‘The Green Archer’ eventually sinks under weight of its own convolutions, combined with a lack of any fully sympathetic or charismatic characters, and a failure to deliver anything truly memorable or outlandish.

Most egregiously, The Green Archer himself is given very little to do, ultimately playing only a minor role in proceedings. A decision seems to have been taken to keep the phantom bowman either entirely off-screen or confined to the shadows, which strikes me as a very bad move. After all, the titular evil-doers in Monk with a Whip or The Face of the Frog weren’t at all shy about turning up to wreak on-camera havoc on a regular basis, lending a sense of berserk surrealism to proceedings which is sorely missed here.

That said though, after dragging rather dreadfully through its middle half hour, ‘The Green Archer’ does at least come to life a bit in its final ten minutes, briefly descending into all-out chaos as Abel Bellamy launches all-out war against the men of Scotland Yard, who are attempting to lay siege to his castle.

Suddenly, we’ve got machine guns blazing, detectives brandishing fizzing, cartoon-style bombs, half the remaining cast desperately trying to escape from one of those classic rapidly flooding dungeons, Eddi Arent roaring around in a weird little car… and all is right with the world.

This is all topped off with my favourite bit of ersatz-English weirdness in the film, which occurs during the the closing wrap-up scene, where we find a burly police constable moving between the shell-shocked survivors, sternly offering them “TEA WITH RUM” - a hearty beverage which seems to perfectly capture the essence of this uniquely odd sub-genre, and which I will henceforth make a point of enjoying each time I brave a visit to Krimi-land.

----

(1)Quoth IMDB trivia: “The producers originally wanted Wolfgang Schnitzler to become on of the regular writers of their Edgar Wallace Series. When Schnitzler’s script of this film was re-written by Jürgen Roland’s regular screenwriter Wolfgang Menge, Schnitzler was displeased and decided to leave the series.”