So, we’ll be doing this end-of-year thing a bit differently this time around. Frankly, those ‘best first-time watches’ lists I’ve put together in previous years were starting to get a bit unwieldy, especially when I don’t currently have much free time to write them. And besides, I’m sure no one really needs a few rushed paragraphs from me to inform them that films I happened to watch this year by Alfred Hitchcock or Ken Russell or Paul Thomas Anderson are good, right..?

Instead then, what I thought I’d do is put together a quick top ten, counting down the best NEW DISCOVERIES I’ve made within the field of film and TV during 2022 - covering things which I was previously unaware of, or which surprised me or surpassed my expectations, and which readers may have overlooked.

As it happens, the majority of my picks are available on shiny new blu-ray discs - reflecting both the unprecedented quantity of obscure and outrageous fare currently being repurposed in glorious HD, and the fact that I’ve not really had a chance to delve much deeper into the celluloid netherworld this year. So, where possible, I’ll include purchase / further info links here too - thus hopefully giving you enough time to ensure that all-important copy of ‘A Haunted Turkish Bathhouse’ is under the tree for a loved one by xmas eve.

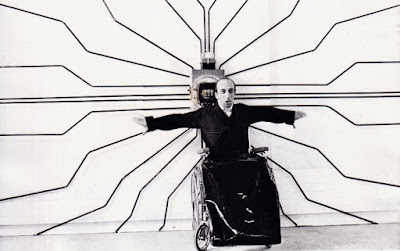

10. The Unknown Man of Shandigor

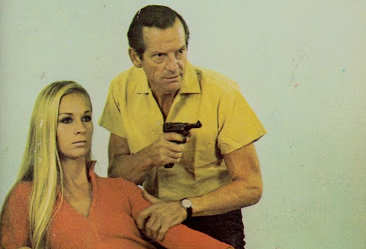

A world away from the garish, over-saturated excess we tend associate with the ‘60s Euro-spy cycle, Swiss director Jean-Louis Roy’s convoluted tale of rival espionage agents battling to obtain the secrets held in the bonce of an unhinged, misanthropic scientist employs an austere, art-damaged aesthetic and a bone dry vein of surreal humour which may prove an acquired taste for some viewers. If you can hit it in the right, suitably continental, frame of mind though, it’s surely one of the most remarkable cult film excavation jobs of recent years.

A world away from the garish, over-saturated excess we tend associate with the ‘60s Euro-spy cycle, Swiss director Jean-Louis Roy’s convoluted tale of rival espionage agents battling to obtain the secrets held in the bonce of an unhinged, misanthropic scientist employs an austere, art-damaged aesthetic and a bone dry vein of surreal humour which may prove an acquired taste for some viewers. If you can hit it in the right, suitably continental, frame of mind though, it’s surely one of the most remarkable cult film excavation jobs of recent years.

Essentially coming on like Bergman getting side-tracked in Alphaville on the way to a Jess Franco set, the film’s extraordinary cast and quasi-futuristic framing of familiar French and Spanish locations often plays out like a fever dream a connoisseur of ‘60s European cinema might experience after an evening spent demolishing a particularly fecund cheese board. So, best put consideration of the film’s obscure symbolism and interminable exposition aside, and instead prepare to revel in the wealth of never-before-seen pop cultural wonders it offers.

The cadaverous Daniel Emilfork (best known to horror fans as that grim reaper guy from ‘The Devil’s Nightmare’) spitting spiteful abuse at the world’s press before eventually sacrificing himself to the (unseen) monster in his swimming pool; Howard Vernon leading Anna Karina lookalike Jacqueline Danno through a dizzying dance of love amid the dinosaur bones of the Paris Muséum National D’Histoire Naturelle (also featured in Chris Marker’s ‘La Jetée’); and, perhaps best of all, Serge Gainsbourg as the leader of a cabal of bald-headed, turtleneck-clad assassins, performing a characteristically crepuscular lament for a dead agent (‘Bye Bye, Mr Spy’) on the organ of a candle-lit gothic funeral parlour.

Frankly, why are you still reading this when you could be buying a copy of Deaf Crocodile’s Region A blu-ray release?

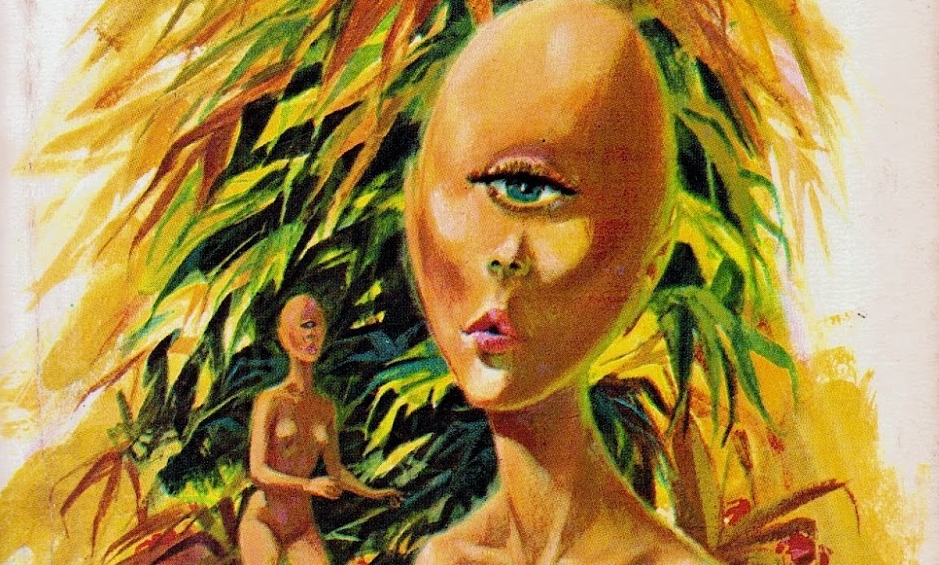

Hair-raising stuff here and no mistake, as director Yamaguchi (who previously brought us Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope and ‘Sister Street Fighter’) attempts an audacious cross-pollination of Japan’s traditional Bakeneko / ghost cat sub-genre and a Roman Porno-styled roughie sexploitation flick, all in finest, deranged mid-‘70s Toei style.

As you might well imagine, a bit of a ‘content warning’ is probably required here, as we need to advise that, in addition to assorted outbursts of vaguely consensual sleazoid sex, ‘A Haunted Turkish Bathhouse’ includes several rapes and one exceptionally unpleasant scene of sexualised violence… but, the jarring shifts in tone which result from this are nothing seasoned Pinky Violence viewers won’t be able to take in their stride, and, very much in the vein of the aforementioned Yamaguchi joints, the film’s wildly OTT pop / comic book aesthetic easily overcomes any lingering grimness, with frantic pacing, freaky gel lighting, and a totally zonked out psych-jazz score from Hiroshi Babauchi very much the order of the day.

In fact, for all its prurient excess, the first hour of ‘Haunted Turkish Bathhouse’ actually functions surprisingly well as a pulpy melodrama. Aided by a brace of wonderfully florid performances from Nikkatsu S&M queen Naomi Tani, regular Toei wardess/madam Tomoko Mayama and the ubiquitous Hideo Murota (going all out as the rascally, lip-smacking villain of the piece), it certainly feels less rushed and more skilfully put together than many of the scrappy, tossed off karate flicks which were filling Toei’s production slate by the mid-‘70s.

Indeed, prime Kaidan atmos and photography are in full effect throughout, and, when the astoundingly crazy bakeneko cat-monster (a close cousin of the one previously seen in Nobuo Nakagawa’s Ghost Cat Mansion (1958), I suspect) finally shows up and starts wreaking havoc in the final act, well…. hopefully fans of global cult cinema will get my meaning if I describe what happens next as Peak Mondo Macabro, delivering a heroic dose of pretty much everything that fine label stands for.

In fact, if the film has one failing, it's that at this point I pretty much forgot about the revenge narrative, turning off my brain and just enjoying the ride as blood sprayed, lightning crashed, cats howled, angles went dutch, fuzz guitar roared and freaky/primitive ‘Housu’-esque special effects did their thing. As fine an evening’s entertainment as could possibly be imagined for my money, but… perhaps one best enjoyed when your more faint-hearted co-habitants are out for the night?

Buy the Region A locked Mondo Macabro blu-ray here, if you dare.

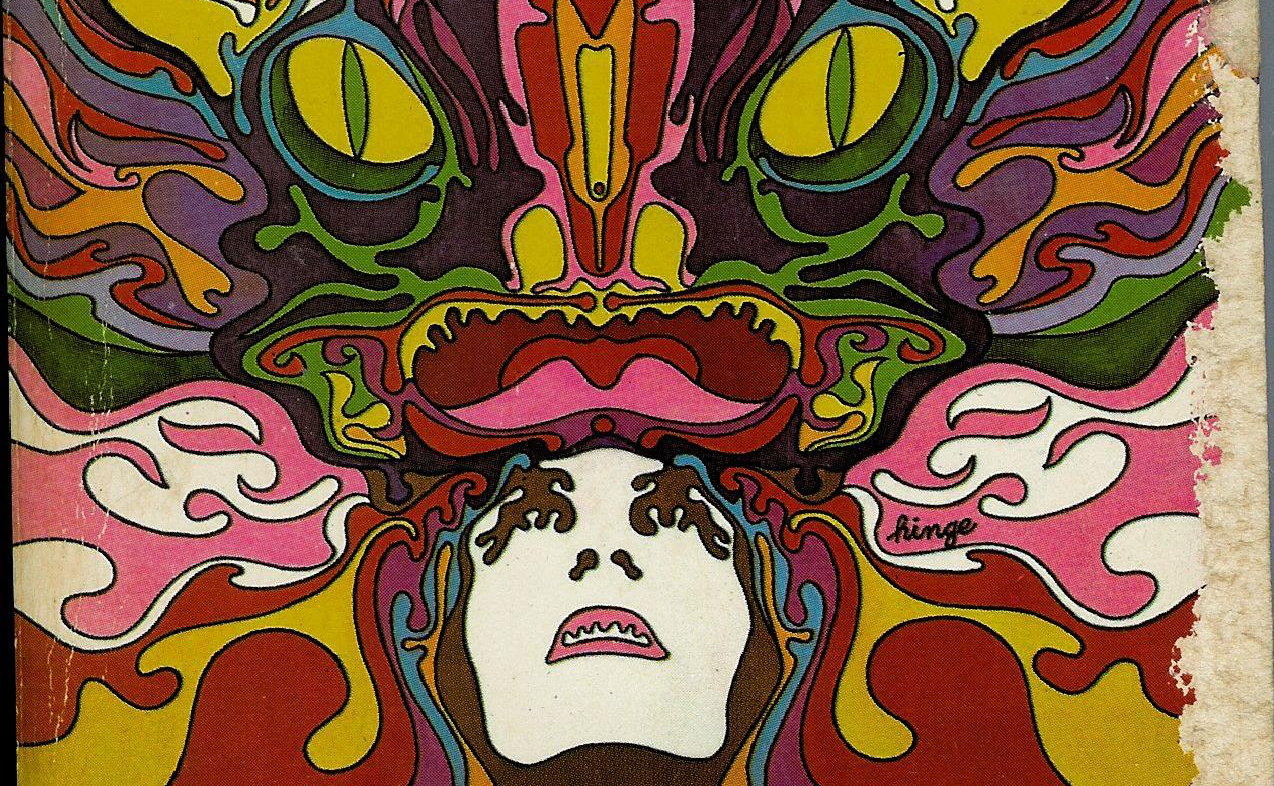

A strange and rather beguiling ten part BBC drama series adapted by producer Anna Home from Peter Dickinson’s series of post-apocalyptic young adult novels, ‘The Changes’ begins the way any worthwhile bit of ‘70s Children’s TV SF rightfully should - with a series of inexplicable, terrifying events guaranteed to disturb any right-thinking child to the very core of their being.

Within minutes of the first episode’s opening credits, unnerving bursts of feedback are ringing out amid stock footage of fire and explosions, as the adult residents of a quiet Bristol suburb are consumed by a sudden madness, compelled by forces unknown to drag anything vaguely resembling a machine out into the street and savagely destroy it. Why is this happening? And what did those poor bicycles ever do to anybody..!?

Answers to these questions are clearly not going to be forthcoming any time soon, as docile teen Nicky (Victoria Williams) finds herself discombobulated by the same strange impulses afflicting her elders. Separated from her parents as they attempt to flee ‘the terror’ by boarding a ramshackle boat to France (first rule of British post-apocalyptic SF: things are never better in France), Nicky soon befriends a caravan of first generation Sikh immigrants, who, fleeing the ‘disease’ which apparently now blights the cities, march out into the countryside and there establish a liberal idyll of rural self-sufficiency, rising above the superstitious racism of tweedy, ale-swilling villagers and dispatching evil, black-clad ‘robbers’ in bouts of polite, Sealed Knot style combat.

Nicky’s subsequent adventures meanwhile find her put on trial as a witch by an aspiring Matthew Hopkins-type for the crime of getting too close to a tractor, enjoying a nice canal journey, contemplating the concept of ‘necromancer’s weather’, and, eventually, communing with a sentient, glowing monolith which may or may not contain the ancient magic of Merlin himself.

Running the gamut of pretty much everything which helped make British culture in the early 1970s so disquieting, thought-provoking and weirdly beautiful, Nicky’s travails are accompanied - almost inevitably - by an astoundingly good soundtrack from Radiophonic Workshop mainstay Paddy Kingsland, whose optimistic, world weary synth melodies, gentle hand percussion and questionable-though-well-intentioned use of tabla and sitar for the Sikh storyline zeroes in so perfectly (nigh, movingly) on what we’d now define as the ‘hauntology’ aesthetic that you’re inclined to wonder why the whole Ghostbox crew even bothered trying to compete.

Though seemingly out of print, the 2014 BFI DVD release of ‘The Changes’ is still easily obtainable for the price of a pub lunch, as is the 2018 Silva Screen vinyl release of the soundtrack, if you know where to look (hint: ask Norman).

Murky natural lighting and ‘stolen’ street corner locations initially lend a bit of an amateurish feel to this low budget L.A. revenge opus (word is, the film’s assigned cinematographer was a drunk, so they muddled through without him). Stick with it though, and it soon develops into one of the most rewarding and idiosyncratic American crime movies the ‘80s had to offer.

Murky natural lighting and ‘stolen’ street corner locations initially lend a bit of an amateurish feel to this low budget L.A. revenge opus (word is, the film’s assigned cinematographer was a drunk, so they muddled through without him). Stick with it though, and it soon develops into one of the most rewarding and idiosyncratic American crime movies the ‘80s had to offer.

Chiefly, the film’s success rests on the shoulders of perpetually underrated leading man Robert Forster, who delivers a nigh-on career-best performance here as failed athlete / taxi driver / bagman Jason Walk (what, did ‘Jason Edge’ get vetoed by the producers or something?!), pouring enough heart, soul and down-at-heel charm into this sad sack character to draw in even the cagiest of viewers.

Plot crashes in as Walk gets mixed up with a woman (Nancy Kwan) seeking bloody revenge on the low-life thugs who killed her family, allowing him - through the tried and tested means of opportunistic romance and something-vaguely-resembling heroism - to regain some purpose in life. But, more often than not, ‘Walking the Edge’ basically just plays out like a hang-out movie for psychopaths, as Forster endlessly cruises the kind of seedy, non-descript locales rarely frequented by even the most adventurous film crews, exchanging semi-improvised patter with a murderer’s row of scene-stealing underworld oddballs.

With the supporting cast presumably pushed to excel themselves by Forster’s Oscar-worthy chops, the film begins to some extent to feel like some mutant step-child of a New Hollywood-era ‘actor’s movie’ (Scorsese on the skids, perhaps?), but this impulse sits uneasily next to the frequent outbursts of harrowing, gory violence which punctuate the chat - much of it perpetrated by the immortal Joe Spinell, bringing the same greasy, hobbling, almost sub-human vibe he perfected in Bill Lustig’s ‘Maniac’ (1980).

Simultaneously pathetic, terrifying and hilarious, Spinell and his mouth-breathing cronies inexplicably hang out at a punk club (well, more of a storefront bar really), in which a teenage band are constantly playing their shambolic first gig in front of their eight devoted fans. Less than impressed, Forster at one point grabs a character listed in the credits as ‘Punk Rock Bartender’ and tells him, “you can take this music of yours and shove it up your KAZOO!” - ironic given that our ‘hero’ has only just finished shoving a knife up the ‘kazoo’ of one of Spinell’s underlings in the men’s room; just one of many unforgettable moments in Meisel’s bizarrely heart-warming accidental masterpiece.

Rehabilitated on blu-ray in the U.S. by the ever reliable Fun City Editions, a UK release of ‘Walking the Edge’ is apparently on the cards for 2023 - an initiative which I feel should be wholeheartedly embraced.

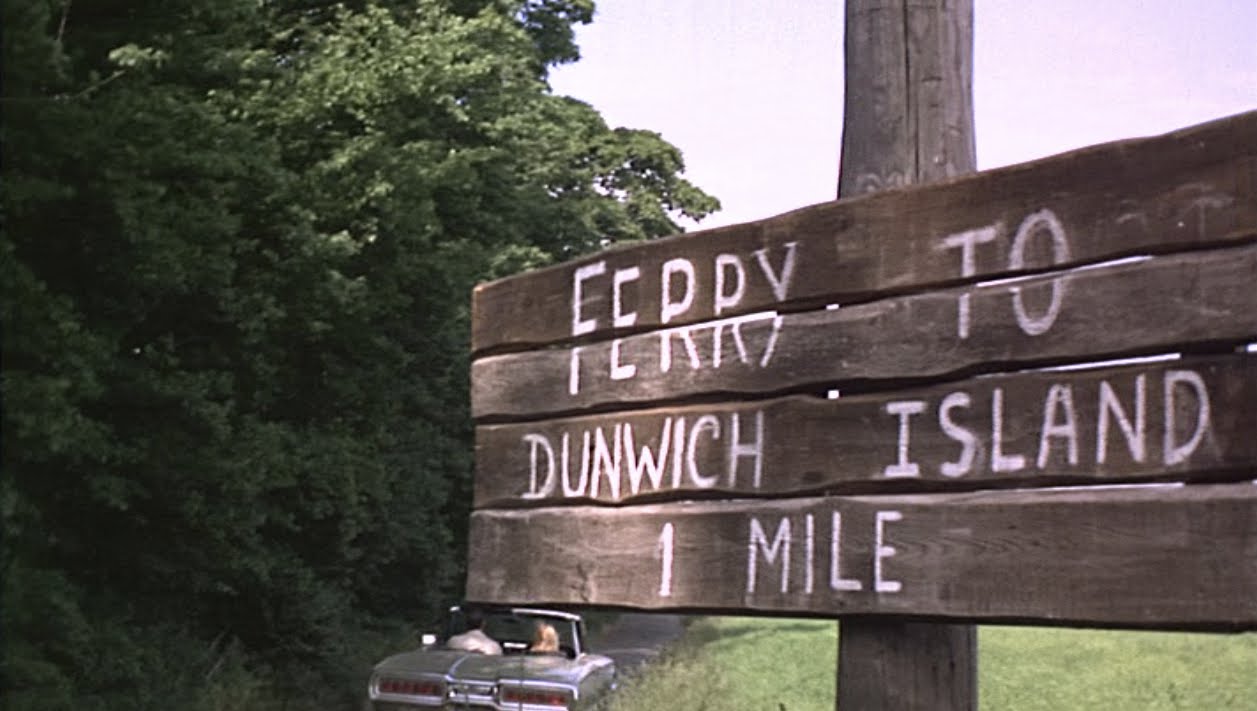

Another dose of pure Robert Forster brilliance here, as he heads up

the cast of what stands as by far the best ‘Jaws formula’ movie I’ve

seen outside of the big originator itself. (Yes, even better than ‘The Car’.)

“Proof that cheap doesn’t have to mean bad,” quoth the oft-cynical Michael Weldon in his hallowed Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, and it’s easy to see what he meant. A sharp, politically-engaged script from John Sayles (fresh off the similarly over-achieving ‘Piranha’) makes it a lot easier to take this tale of a 35-foot monster-gator seriously than than one might have imagined, and tense, tightly-wound direction from Lewis Teague seals the deal.

Great faces like Michael V. Gazzo, Dean Jagger, Mike Mazurki and the late Henry Silva (R.I.P.) fill out the supporting cast - the latter playing a memorable variation on the Quint archetype - whilst the special effects, mixing close up puppetry/suit work with cannily framed long shots of real gators traversing miniature sets, are - I kid you not - the most effective I have ever seen in a giant monster movie.

Not much more to say here really, except to suggest that, if you only watch one movie about a giant reptile wrecking havoc in your life… well, best make it Ishiro Honda’s ‘Godzilla’. If you’ve got room for two though, ‘Alligator’ is where it’s at.

(Oh, and, word to wise: avoid the 1991 sequel at all costs, it’s awful.)

I watched this streaming on Shudder, but in terms of physical media, it’s most recently surfaced as a 4K UHD from Shout Factory. Worth every penny, I’m sure.

To be continued…