I thought I had pretty much mapped out the entirety of the ‘hippie horror’ sub-genre a few years back (around the time I started making this thing), but these unexpected stragglers just keep dragging me back in.

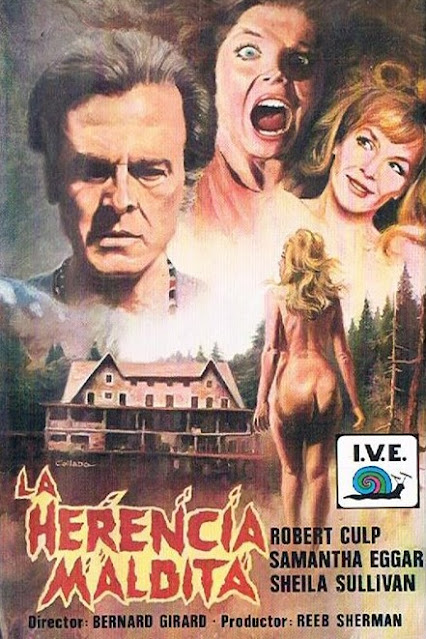

On the surface of things, ‘A Name For Evil’ appears to be a sort-of-haunted house movie, theatrically released in ’73 with name stars Robert Culp and Samantha Eggar. Writer/director Bernard Girard was a TV veteran who occasionally made the jump into features, but even his one paragraph IMDB bio notes that “the majority of his film output has been routine”.

Cueing this up of a weekday evening, I was expecting, I suppose, some fuzzy, bucolic mid ‘70s TV movie vibes. Perhaps a bit of a pre-Stephen King, ‘Flowers in the Attic’/‘Burnt Offerings’ airport paperback kind of feel?

Well, I certainly got all of that. Indeed, we’ve got sun-dappled ‘70s cathode ray ambient gorgeousness as far as the eye can see. But, I also got so much more… and simultaneously, also kind of… much less, if you know what I mean (man).

Right from the outset, things are a bit… off. The distinctly Corman/Poe-esque opening titles consists of super-imposed/interweaving close-ups on a series of Bosch-via-Bacon expressionist paintings. Even more unnervingly however, the titles appear to have been set in some ‘70s equivalent of comic sans, and inform us that this is a “a Penthouse Production presentation”. Hmm.

The weirdness continues as footage of sunshine shimmering on water is cross-faded with images of construction cranes, cement mixers and skeletal tower blocks. “I don’t wanna build filing cabinets twenty stories high,” construction company exec John Blake (Culp) protests in voiceover. “I wanna build something beautiful! Every time I come into the office it makes me sick - I’m getting outta here!”

I don't know whether he’s turned on and tuned in yet, but John Blake is certainly ready to drop out. He wears a mustard yellow shirt, a funky neckerchief and brown leather jacket, and tells his middle-aged secretary that she’ll soon be “wrapped in cellophane, on sale for 49 cents a pound” if she doesn’t quit her job.

Via fragmentary, vérité type footage reminiscent of a ‘Medium Cool’/‘Putney Swope’-esque counter-culture satire, we see Blake triumphantly quit the rat-race for good, leaving his enraged brother/partner to pick up the pieces. (“You’re as loony as your great-grandfather The Major, and you’ll end up the same way - nuts!”)

Returning to his penthouse apartment (or, “this infernal plastic anthill”, as he likes to call it), Blake continues to talk anti-materialist turkey with his presumably long-suffering wife Joanna (Eggar). Obviously their relationship is on the rocks (because, y’know - the ‘70s), but John hopes that his plan to relocate to (and subsequently renovate) a beautiful yet dilapidated lakeside timber frame mansion he has recently inherited will bring them back together.

He also takes the opportunity to throw his television set off the balcony, allowing us to watch it descend to the ground and shatter in slo-mo, ‘Zabrinskie Point’-style (a particularly sweet moment for director Girard, one imagines), just in case he hadn’t quite made his point clearly enough yet.

Later that evening, John is rapping in the general direction of his sleeping wife, telling her how they’re going to “..find out the truth, together” (try looking for it when she’s awake next time dude, I think you’ll find that yields better results), when suddenly, without warning, sitars and tamburas are blaring on the soundtrack, and we cut to gel-lit, heavily super-imposed footage of naked, bead-covered dancing girls gyrating to the sound of a drowsy, finger-picked guitar which has joined the ersatz Indian drone. Sound the klaxon! Red alert! We’ve got some full strength hippie shit going on here.

Never fear though, it all vanishes as quickly as it arrived, and after a brief fantasy sequence in which Culp and Eggars try to embrace through a pane of glass (SYMBOLISM), we’re back in the ‘real’ world. It goes without saying of course that the aforementioned mansion has reached John’s ownership through the family line from the aforementioned ‘Major’, and, once the couple reach it, they learn - much to John’s joy and Joanna’s chagrin - that it is also both, a) completely uninhabitable, and b) located way out in the back of beyond, with nothing but suspicious, gimlet-eyed creepy locals as far as the eye can see.

Particularly notable in this regard is Jimmy (inexplicably played by Kansas City jazz legend Clarence ‘Big’ Miller), the mansion’s simple-minded live-in caretaker, whose role seems to consist of lumbering around refusing to do any work, creeping up on people when they least expect it, and occasionally muttering things like, “once the Major’s, always the Major’s”. (A pretty demeaning, racially stereotyped role for a renowned musician like Miller to take on, I would have thought, but… who knows.)

Anyway, things progress more or less as one would imagine, and, in terms of both plot and atmosphere, ‘A Name For Evil’ seems to fit squarely into the “city folk with back-to-nature aspirations hit the country and get more than they bargained for” mould of ‘Let’s Scare Jessica To Death’ (1971) or Dark August (1976).

But then, during the second half of the film, things get increasingly tripped out and unglued - so much so that it started to put me more in mind of, I dunno, Brianne Murphy’s ‘Blood Sabbath’ (1972 - real dark heart of brain-fried regional hippie horror, that one) or Tonino Cervi’s witchy political allegory ‘Queens of Evil’ (1970), with a touch of Altman's nightmarish ‘Images’ (’72) lurking about in the background somewhere too.

Before we get to all that though, I must confess that I kept nodding off whilst trying to watch ‘A Name For Evil’ - a factor which would normally prohibit me from attempting to review a film, but in this case, I’ll make an exception. Because, the fact is, ‘A Name For Evil’ is a great film to fall sleep to - so much so that it often feels like it could have been made explicitly for that purpose.

Once the basic set-up has been established, very little happens. The horror element is extremely mild and unthreatening (basically just the ghost of The Major turning up occasionally to whisper in people’s ears or interfere with some building work), whilst the whole thing is so dream-like and sedate already, what with all those fuzzy, bucolic forests and shimmering lakes... after a while, you just end up closing your eyes and going to nice places. It’s inevitable. Just go with it.

At some point about two thirds of the way through the film, I awoke from a little snooze to find Robert Culp was riding a spectral white stallion through the forest to some kind of local bar / barn dance place, where there are campfire sing-alongs and wrestling contests going on, huge platters of spaghetti are being thrown around, and folk-pop singer Billy Joe Royal is on stage, performing his song ‘Mountain Woman’. (1)

Blake begins dancing with a blonde woman (Culp’s real life fourth wife Sheila Sullivan). She tears his shirt off, and suddenly the camera goes fish-eye crazy and everyone is naked! There are human pyramids of head-banging naked people. Billy Joe Royal is surrounded by naked girls as he strums his guitar. It’s a kaleidoscope of nudity!

Then, we’re outside, and there are are weird, naked pagan hippie ceremonies going on out in the woods. Culp and Sullivan make wild, passionate love on the forest floor, as the distant strains of ‘Mountain Woman’ reverberate ceaselessly in the background.

I'm pretty sure I didn't dream any of that. I think it all happened... within the movie, I mean. Whether or not it happened to Culp’s character, who can say.

Crawling back to the shack the next morning like a soggy tom-cat, John slips indoors and immediately gets into a situation with Joanna, who gives him hell for ruining her sleep, insisting that he actually spent the night next to her, “masturbating like a fourteen year old child”(!) This line is subsequently repeated several times in voiceover (as if it wasn’t bad enough the first time around), as Culp wanders around amid his beloved nature, looking aggrieved, and presumably reflecting on his inability to separate fantasy from reality, or somesuch.

But then, he drives back to the bar / barn dance place (so I guess it must be real?), and meets up again with the blonde woman (so I guess she was real too?), and they start having heavy conversations about, y’know…. life, and stuff.

Man, what a weird movie. It only marginally counts as horror, but the half-hearted supernatural elements, creepy atmospherics and monied, middle-aged protagonists jibe so strangely with the discombobulated psychedelic / counter-culture stuff which takes up so much of the run-time… just where in the hell was this thing coming from? And more to the point, where was it going? (Cos either way, I have a feeling it didn’t quite get there.)

Once again, we must turn to the oracle of the IMDB trivia page for answers:

“Filmed in 1970 as a psychological thriller that parodied then-modern society, production swelled over budget and MGM ultimately shelved the movie. Three years later, Penthouse magazine's movie division acquired the rights to re-cut the film and market it as a horror movie.”

Well, I suppose that helps clear a few things up (not least the film’s persistent reliance on off-screen voiceovers), but… I mean… I’m still not sure this version of events quite makes sense.

I mean, one assumes Penthouse’s number one priority would have been adding more sex to the film, but, all the gratuitous nudity and weird orgy stuff occurs within the hippie/counter-culture sequences which I’m pretty sure must have formed part of the original 1970 footage. OR, did Penthouse actually acquire this film BECAUSE it had loads of naked people in it, and then realised that the rest of it was a load of (by ’73) heinously outmoded hippie blather, so tried to turn it into a horror film instead..? But, that scenario doesn’t work either, because visual elements of the ‘horror’ plotline (ie, the ghost of and the spooky occurrences he instigates) are embedded within footage featuring the principal cast and original locations from 1970, so…. agh, I don’t know.

Goddamned hippies. They never make it easy for us, do they? Whatever untold stories lurk behind the battered extant prints of ‘A Name For Evil’ though, they don’t really matter. It is what it is, and I make no apology for loving this kind of ambient, plotless weirdness and the unique and beautiful moment in culture which allowed it to exist, so… yeah. Dig it, and so forth.

At the time of writing, a tape-sourced print of ‘A Name For Evil’ can be acquired free of charge from Rare Filmm.

---

---

(1) Quoth Wikipedia: “Billy Joe Royal (1942 - 2015) was an American country soul singer. His most successful record was ‘Down in the Boondocks’ in 1965.” Insofar as I can tell, ‘Mountain Woman’ does not appear in his discography of recorded work, but it was written by acclaimed session player and producer Emory Gordy Jr, with lyrics by Ed Cobb - the man who gave the world The Standells’ ‘Dirty Water’, Gloria Jones’ ‘Tainted Love’ and the career of The Chocolate Watch Band, amongst other things. Far out.

1 comment:

I totally agree with your assessment of 'The Silent Partner'. I watched it again last year after the passing of Christopher Plummer and it was every bit as good as I remembered it.

When I first saw it on TV in the 1980s, it was quite an education. As much as 'An American Werewolf in London' did, it showed me that if you blended humour and horror (or simple, dark nastiness in 'Partner's case), and treated both the humour and horror with respect, and didn't make either thing too broad or goofy, you could end up with a memorable film indeed.

By a coincidence, I saw 'Partner' again the same week that I watched Hammer's 1961 crime noir 'Cash on Demand' for the first time. This has an uptight bank manager (Peter Cushing) tormented by a sadistic criminal (Andre Morell) who wants to enlist his help in a robbery. Though they belong to different eras and different filmmaking cultures, the similarities between the two movies are uncanny -- especially as they're both set at Christmas. Maybe they'd make a good double-bill to watch next festive season...?

Post a Comment