Showing posts with label manga. Show all posts

Showing posts with label manga. Show all posts

Thursday, 23 April 2020

Stuff to look at:

Imiri Sakabashira.

Imiri Sakabashira.

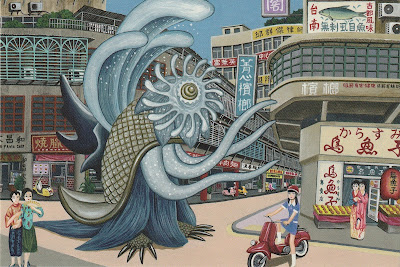

It’s been an age since I’ve done any posts focussed on art or design here, but given that I’ve not really had any time to write about movies during the past few weeks (believe it or not), here for your viewing pleasure are scans of a set of postcards which until recently were pinned up in my kitchen. (I’ve temporarily taken them down to facilitate some much-needed lockdown re-painting.)

These are the work of underground cartoonist and manga creator Imiri Sakabashira, a somewhat mysterious figure (to us English speakers at least) whose work first saw publication in 1989. About the only other biographical info I can find is that he was born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1964. His gekiga manga The Box Man was published in translation by Drawn & Quarterly in 2010.

I bought these postcards from the Taco Ché underground culture/zine shop in Nakano, Tokyo a couple of years ago, and, as can be plainly observed, their combination of naturalistic urban street scenes, pseudo-Lovecraftian kaiju / yokai monstrosities and retro/pop art iconography is guaranteed to blow your (or at least, my) mind, anytime.

More of Sakabashira’s art can be seen via this 2009 post from the much missed Tokyo Scum Brigade blog, which also informs us that the artist is “..a prominent ero-guro artist from the avante-garde manga magazine Garo” [sic] and “..a big name in the underground manga scene”.

I also nabbed the following doozy of a jpg from a Pinterest page.

In conclusion: rock on Imiri. This stuff is amazing.

Labels:

art,

comics,

illustrators,

Imiri Sakabashira,

Japan,

kaiju,

manga,

modern pulp,

monsters,

pop art fantasias

Sunday, 23 December 2018

2018: BEST READS.

(Part # 2)

(Part # 2)

The Virgin of the Seven Daggers:

Excursions into Fantasy

by Vernon Lee

(Penguin Red Classics, 2008 /

collection originally compiled in 1962)

I think this was from the remaindered bookshop in East Dulwich? Price sticker on the back says £3.

Vernon Lee was the pen name of writer and art historian Violet Paget (1856-1935), and funnily enough, a very strange hardback compiling some of her work was one of the first books I ever scanned and posted on this weblog, way back in 2010. The best part of a decade later, I’ve finally found time to read some more of her work, courtesy of this recent Penguin edition, reprinting a ‘60s anthology of a set of stories originally published between about 1890 and 1910, I believe.

A remarkable personage by any yardstick, Paget/Lee may have been ostensibly English, but she was born in Boulogne and spent the vast majority of her adult life on the continent, eventually settling in Florence. In addition to her fiction, she wrote extensively on European travel, history and culture, and in her day she was considered a leading authority on the Italian Renaissance, as well as an enthusiastic advocate of the Aesthetics movement pioneered by Walter Pater in the late 19th century.

All of this comes across very strongly indeed in her ghost stories, which – in stark contrast to the Anglican parochialism favoured by her near-contemporary M.R. James – are all set in Southern Europe (Italy, and sometimes Spain or Greece), and are chiefly notable for their dense and intoxicating tapestry of esoteric historical detail, blending references to art, architecture, music, geography, aristocratic lineage, religious traditions, local legends and sundry other oddities into such a rich, brooding atmosphere of quasi-fantastical grandeur that it is difficult for an ignoramus such as myself to ascertain where her reportage of authentic period detail ends and her imagination begins.

The opening tale, ‘Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady’, concerns the illegitimate son of one Prince Balthasar Maria of the Red Palace at Luna, who, after incurring the Prince’s disfavour, finds himself exiled to a remote outpost of the kingdom, where he falls victim to the charms of the same predatory female snake spirit who did a number on one of his illustrious ancestors. (Mixing a decadent, fantastical atmosphere with a sardonic sense of humour, this miniature masterpiece was originally published in an 1895 issue of the notorious Yellow Book.)

‘Amour Dure’ meanwhile concerns a highly-strung young Austrian scholar who, whilst undertaking historical research in a mountainous Italian town, develops an unhealthy obsession with a notorious, Lucretia Borgia-like femme fatale who features prominently in the area’s folklore, and – in classic Jamesian fashion – pays dearly for his temporally unsound ardour.

‘A Wicked Voice’ – in which a similarly self-absorbed young composer working in Venice becomes haunted by the voice of an 18th century singer credited with uncannily abilities – has a disturbingly unglued, dream-like feel to it, culminating in a set-piece that feels as if it could have been shot by Dario Argento or Pupi Avati.

Most memorable of all though is probably this collection’s title story, a Spanish number in which the notorious sinner and womaniser Don Juan Gusman del Pulgar, Count of Mirador, uses fiendish necromancy to gain access to a secret subterranean world concealed beneath a tower of the Alhambra at Grenada, there to take possession of the ‘Moorish Infanta’, a Princess Bride who has lain there through the centuries in unholy, magical slumber. It’s quite something.

Needless to say, Vernon Lee’s fiction remains unfairly overlooked, and ripe for rediscovery. Although she began publishing these stories some years before James, they nonetheless represent a series of head-spinning twists on the same basic formula, so, if you’re in search of something a bit different for your Christmas ghost stories this year, look no further.

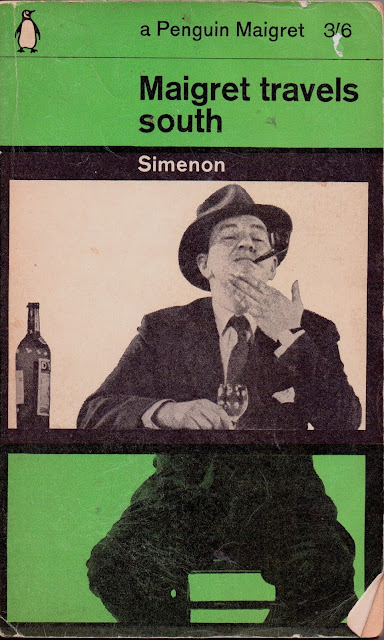

Maigret Travels South by Georges Simenon

(Penguin Crime, 1963 /

originally published 1940)

No idea where this one came from. All those Penguin crime purchases blur into one, especially the Maigrets. I’d buy ‘em by the kilogram if I could. (The cover shows Rupert Davies as Maigret, from the BBC TV series.)

For some reason, my favourite Maigrets always seem to be the ones that take him outside of Paris. With typical Simenon wit, this particular short novel sees the Chief Inspector “travelling south” in more ways than one as he arrives in Cannes to investigate the case of a dilettante Australian wool millionaire found stabbed to death on his own doorstep.

Routine sleuthing soon leads Maigret to the backroom of the ‘Liberty Bar’, a commercially redundant, essentially closed establishment where the food is good and the landlady accomodating, but where the air is also heavy, with a persistent atmosphere of fated, self-indulgent melancholy hanging over the handful of down at heel, demi-monde denizens who congregate there.

Like all of the best Simenon stories, this is one in which Maigret’s personal inclinations and human sympathies find themselves directly at odds with his obligations as a detective, and in which he thus finds himself weighed down by the guilt of knowing that his intrusion into the small, self-contained world of the story’s characters – so beautifully drawn by Simenon – has led, inevitably, to its destruction.

Though perhaps no great shakes as a mystery, these hundred-and-something pages pack a considerable emotional punch, knotting up some of the same bits of your insides as the best literary noir. Highly recommended.

MW by Osamu Tezuka

(Vertical Inc hardback, translated by Camillia Nieh, 2007 /

originally serialised in Biggu Komikku manga, 1976-78)

This was a birthday present – thank you Satori.

Osamu Tezuka (1928-89) exercised such a profound influence over the development of Japanese manga as we know it today that some subsequent fans and creators have gone so far as to treat him as an actual, literal God – a claim that begins to make a certain amount of sense when one considers both his staggeringly prolific work-rate and the consistently high quality of his precise, impactful artwork and conceptually innovative storytelling.

Although Tezuka remains best known in the West as the creator of the iconic Astro-Boy, and for his epic, multi-volume biography of the Buddha, his later years saw him expanding into darker, more adult-orientated territory, drawing somewhat on the Taisho-era Ero-Guro tradition of writers like Edogawa Rampo, but blending this influence with his own stark, modernist aesthetic, pushing the limits of his imagination in ever more extreme directions.

Sprawling across over 500 densely-packed pages, ‘MW’ arguably represents the culmination of this particular strain of Tezuka’s work, and describing its contents as “dark” feels woefully inadequate.

Though impossible to summarise in full, the story here centres on the intertwined fate of a grown man and a young boy who – for reasons too convoluted to go into here – find themselves spending the night in a cave on the coast of a remote island. Venturing out the following morning, they discover that the entire population of the island has been exterminated by what is later revealed to have been a deadly experimental nerve gas named MW, stored there by the American military.

Years later, the older man has become a Catholic priest, but he is still driven to tormented, soul-endangering distraction by his continued association with the young boy, who – after nearly dying from his exposure to MW on the island - has rather inconveniently grown up to become an androgynous, Fantomas-style super-criminal and master of disguise. Seemingly devoid of human empathy, as if his “soul” had been surgically removed, he commits all manner of terrible and perverse outrages, seemingly for no reason other than his own cruel enjoyment.

In the course of the story that follows, Tezuka pulls no punches in depicting a range of subject matter that takes in genocide, paedophilia, serial murder, rape, bestiality, torture and familial suicide, but does so with a sense of carefully honed, story-driven artistry that pushes the work way beyond the level of mere “transgressive” button-pushing.

Indeed, the obsessive precision of Tezuka’s artwork provides an unsettling contrast to the outrageous, frequently melodramatic, nature of the events he depicts, adding a genuinely psychopathic edge to proceedings that leaves the author’s actual intentions feeling strangely ambiguous.

Should we read ‘MW’ as a meditation on Catholic guilt and the essential nature of evil, or as a bitter commentary (both allegorical and literal) on the malign effects of America’s post-war dominance of Japan? Was Tezuka deliberately setting out to shock and appall his readers, perhaps using extreme imagery to detract attention from the tale’s uncomfortable political sub-text? Or was he simply concocting a vast ‘shaggy dog story’; a needlessly convoluted saga whose pleasures arise simply from the wickedly unlikely contrivances of its surface level story-telling..?

Somewhat inevitably, the best answer is probably “all of the above and much more besides”, but, whatever you end up taking from it, ‘MW’ remains a dangerous, multi-faceted hydra of words and pictures in which we see a master craftsman pushing the metaphorical envelope about as far as it can possibly go, making for an experience not easily forgotten.

UFO Drawings from the National Archives

by David Clarke

(Four Corners Irregulars hardback, 2017)

I bought this directly from Four Corners.

Between 1952 (when Winston Churchill demanded to know “..what all this flying saucer stuff amounts to”) and 2009 (when its operations were quietly shut down, having been deemed to have collected absolutely no useful intelligence whatsoever), The Ministry of Defense’s UFO Desk diligently collected and assessed untold thousands of reported UFO sightings across the British Isles.

Since 2007, when the desk’s files began to be declassified and incorporated into the National Archives, writer and academic David Clarke has been going through them with equal diligence, and as a result has compiled this attractive book, presenting a carefully curated selection of the drawings of alien spacecraft submitted to the MOD by members of the public during the years of the UFO desk’s operation.

As well as providing a wealth of rather splendid examples of quote-unquote ‘outsider art’, these drawings, accompanied by Clarke’s concise and non-judgemental summaries of circumstances surrounding their creation, provide an intriguing insight, not only into some very obscure corners of the 20th century British psyche, but also into what I have always considered to be the essential paradox underlying the UFO phenomenon.

Namely, the fact that, on the one hand, the vast majority of UFO reports are absolutely ludicrous - clearly beholden to the whims of popular culture and so completely lacking in plausibility, consistency or verifiable evidence that the possibility of their literal truth seems extremely unlikely.

But, on the other hand (and this in particular is highlighted by Clarke’s book), there is the fact that many of the people who make these reports do not seem to be the fantasists and attention-seekers that determined sceptics tend to assume, but quote-unquote ‘normal’, ‘sensible’ individuals with no prior interest in the subject, who in fact often seem embarrassed and upset by what they have witnessed, and beg the MOD not to publish their names or risk generating any publicity.

(Perhaps reflecting the demographic most likely to report their experiences directly to the government, a curious number of the witnesses featured in the book seem to have had a connection to the military or aerospace industries, and are apt to provide extremely detailed drawings of the craft they claim to have seen, complete with measurements and notes on construction materials, etc.)

Between these two impressions, something clearly doesn’t add up -- and it is this strange disjuncture which continues to fascinate, even as the fact that most first world citizens now essentially carry a HD video camera around in their pocket seems to have largely relegated UFOs to the status of a nostalgic, 20th century phenomenon.

Non-fiction-wise, I also read a great Pelican book about the history of Latin America this year, but I had to get rid of it because it had bookworm and was falling apart as I read it, so no review.

Labels:

book reviews,

books,

David Clarke,

end of year stuffs,

Georges Simenon,

manga,

Osamu Tezuka,

UFOs,

Vernon Lee

Friday, 5 June 2015

Japan Photo Spectacular:

On (Nakano) Broadway.

On (Nakano) Broadway.

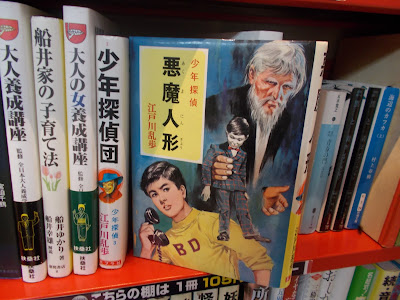

Located within what I assume to be a post-war multi-story shopping arcade in the Nakano ward on the west side of Tokyo, Nakano Broadway probably ranks as one of my favourite places on earth.

An otaku retail paradise, entirely filled with what Wikipedia describes as “subculture speciality shops” (many of them under the umbrella of the ‘Mandrake’ group) Broadway is basically Japan’s mecca for collectors and connoisseurs of every kind of 20th century pop culture memorabilia under the sun, whilst also offering a secondary function as a breathtaking museum of such material for those of us who lack both the knowledge and financial resources to deal, haggle and hoard like true nerds.

As a non-Japanese speaking gaijin and general pop culture fanatic, it is difficult to express the simultaneous feelings of exhilaration and frustration that I experienced whilst exploring some of Nakano’s numerous manga, magazine and paperback fiction emporiums.

Put it this way: when we, as (presumably) Western fans of the kind of thing I cover on this blog, visit a comics shop or second hand bookshop, we can enjoy pulling things off the shelves, having a look at what’s available, and be generally satisfied that we’re broadly familiar with the range and nature of stuff on offer. Japan though is a whole other world: an immeasurably vast ocean of entirely new stuff that we’ve never seen before and will likely never see again, eye-catching imagery and vivid, beautiful images jumping out at us wherever we look, offering many entire lifetimes’ worth of narrative and artistic rabbit holes for us to fall down and lose ourselves within. But the cruel reality of the language barrier is always present – a continual reminder that, barring the possibility of putting all other aspects of our lives on hold to undertake years of intensive study, these worlds are forever closed to us.

(My apologies for the reflections and blurriness present in some of the photos that follow; most of the Nakano shops take a dim view of photography, so my shots were generally taken as quickly and covertly as possible.)

Printed matter aside, one of the chief money-spinners for Nakano Broadway is, inevitably, that of toys, action figures, model kits and other miscellaneous three dimensional franchise memorabilia. As someone who is largely ignorant of this world, I can’t comment on the pricing, rarity or variety of the selection on offer, but I can at least confirm that it was pretty nice to look at, as the shots below will hopefully verify.

Though movie memorabilia plays a comparatively small role in Nakano Broadway’s overall scheme, there is still a lot of great stuff for Japan pop cinema enthusiasts to gawp at, including, to my delight, a huge number of original Toei and Nikkatsu posters, most of them on sale for a far more reasonable amount than I might have imagined. (As I still had about two weeks of nomadic travel around Japan ahead of me at this stage of my visit, can I just say, thank god for Pringles tubes.)

Left: Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs (1974), Right: Female Convict Scorpion: Prisoner # 701 (1971).

A publicity shot of Reiko Oshida in Toei’s Delinquent Girl Boss series, buried amid a pack of random lobby cards and publicity material.

This glossy Reiko Ike photo-book came with a pretty hefty price-tag.

One of the movies Nikkatsu produced for Group Sounds band The Spiders.

No idea what these ones are – any guesses?

Meiko Kaji poster sale – this week only!

Left: Super Gun Lady (1979), Right: Golgo 13: Nine Headed Dragon (1977).

And finally: the unusual painted poster for Fear of the Ghost House: Bloodthirsty Doll (1969), as currently displayed back home in our London flat.

Labels:

comics,

ephemera,

holiday snaps,

Japan,

JH,

manga,

Nakano Broadway,

places,

poster galleries,

pulp fiction,

shops,

travel

Saturday, 16 May 2015

Japan Haul:

‘A Funeral For Maya’

by Ichijo Yukari

(1972)

‘A Funeral For Maya’

by Ichijo Yukari

(1972)

For one reason or another, I never really got around to scanning most of the junk shop treasures I brought back from my trips to Japan last year, or indeed sharing any of the photographs I took of astounding, pop culturally significant locales. With another visit now booked in September though, this summer seems a good time to start ‘clearing the decks’ in preparation for whatever random oddities I fill my suitcase with next time.

Within what I am now declaring to be a loosely connected series of posts here, we’ve already breathed in some Yokai Smoke, viddied a few movie brochures, and enjoyed the extraordinary tale of The Devil’s Harp. What better way to continue then than with another manga - this time, another standalone volume with a title that roughly translates as ‘A Funeral For Maya’. The enticing psychedelic cover artwork caught my eye as I was trying to navigate my way around one of the several gigantic manga emporiums in Tokyo’s Nakano Broadway, and 100Y (approx. 60p / 80c) later, a mass of crumbling low-grade paperstock and lavender inking was all mine.

Born in 1949, Ichijo Yukari remains a phenomenally successful creator of shōjo (‘girls’) manga, and it seems she was already a master of her craft at the age of 22, when this supplement to the popular Ribon shōjo magazine was published in July 1972.

Whilst I can’t give you a full plot synopsis, a rough translation of the introduction on the inside cover goes as follows:

“Maya, a girl who lives for hate and never smiles, meets Reina, a beautiful girl, who lights up her heart with love. The invisible thread of destiny connects them to each other…”

Judging by some of the artwork found within, raven-haired Maya would also seem to be somewhat, uh.. spectrally inclined.. apparently appearing out of nowhere as Reina rides her horse through the woods, and a full-on Sapphic kiss between the two mid-way through the story seems daring to say the least. Deliciously horror-tinged, gothic/romantic stuff, I’m sure you’ll agree. A few select scans can be enjoyed below.

(Thanks once again to Satori for translation assistance.)

Labels:

1970s,

comics,

gothic,

Ichijo Yukari,

Japan,

JH,

lesbianism,

manga,

romance

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)