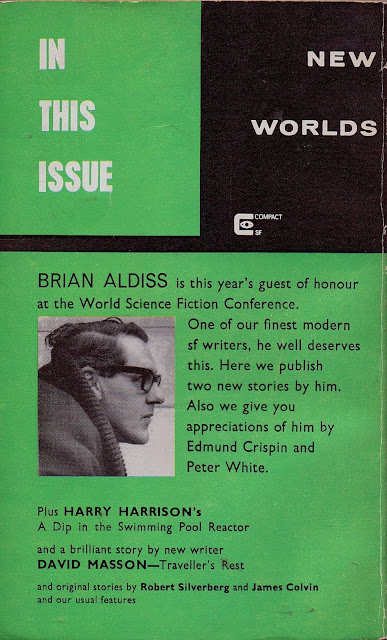

To further mark the recent passing of Brian Aldiss, I thought it might be a good idea to revive my long-neglected ‘Old New Worlds’ thread [click on the ‘New Worlds’ tag below to view earlier posts] to cover the issue that was once, long ago, lined up as the next instalment – an issue that, as luck would have it, is almost entirely dedicated to Aldiss and his work.

At this point in time, New Worlds had largely dispensed with interior illustrations, meaning that this issue contains relatively little scan-worthy material, but we do at least have the wonderfully bizarre, unaccredited cover illustration (is it a photo, some kind of collage..?), whose distorted, sensuous landscape seems a clear reflection of editor Michael Moorcock’s campaign to gradually move the magazine’s aesthetic reach beyond the confines of the stylised spaceships and meteorites that were gracing its covers just a few months earlier.

This seems to lead neatly into a short ‘appreciation’ of Aldiss by Edmund Crispin, which kicks off issue # 154.* Crispin here crowns Aldiss “The Image Maker”, drawing an interesting distinction between science-fiction (which “..can be good even when its visualisation – of a Martian, a metropolis, a mutant – is relatively sketchy and commonplace”) and science-fantasy (in which “..the quality of the visualisation is the all-important thing”), and crediting Aldiss as one the most gifted proponents of the latter strain, despite his embrace of the surface trappings of the former. “Aldiss has a painter’s eye”, Crispin concludes. “Compared with him, almost all other sf writers (take the ‘f’ whichever way you like) work in black and white.”

In his editorial meanwhile, Moorcock gets a little more personal in his praise;

“Apart from being admired for his talent, Brian Aldiss is also amongst the most well-liked of sf writers; charming, ebullient, fluent, not unhandsome, a gourmet and man of good taste and humour, he is as interesting to meet as he is to read. His criticism, in The Oxford Mail and SF Horizons, is intelligent and pithy, matched only by a few.”

If that weren’t enough, we even get a third, quite lengthy, appreciation of Aldiss’s work, from Peter White, who muses;

“However much he may attack the priggish inhumanity of bureaucrats, moralists, and politicians, and suggest that we should take life as it comes, he always deals with sadness more vividly than joy, and his very choice of subjects is mournful. Many of his heroes […] are intelligent plebeians; too repressed to be earthy, and without the well-bred grace to be aristocratic. Filled with a vague sense of loss, they search for a better life. Nearly every one of his major novels takes the form of a quest without any real conclusion. Perhaps it is this that makes his writing seem so valid to the world now, where the bright lights, dark and crowded dance halls, high-speed along the bypass, casual sex and beat music, all seem like drugs to keep us going until we can get hold of something real.”

White also sees fit to note that Aldiss was born in Norfolk “within a stones throw of F.L. Fanthrope” (no prizes for guessing in which direction he might have preferred the stones to be thrown).

For all these fine words though, perhaps the most pertinent summation of Aldiss’s approach to life in this issue comes from the man himself, who is quoted by White as follows;

“I wish to continue to write as I want, and to be published, and to earn a reasonable income, and perhaps in this way to make a contribution to the rich and wonderful culture into which I was born and which, despite all its horrors, never ceases to delight me day by day.”

Gifted as we now are with the knowledge that that is indeed what he continued to do for over fifty further years, I feel this is as good an epitaph as any for what I am certain was a life well spent. R.I.P. Brian.

Elsewhere in this issue’s non-fiction pages, ‘James Colvin’ (previously unmasked in these posts as a beard for editor Moorcock himself [note the initials]) waxes lyrical on the qualities of J.G. Ballard’s recently published ‘The Drought’:

“It is an intellectual and visionary novel of marvelously sustained power and conviction, […] reminding one constantly of the burning landscapes of the best surrealist painters. Its approach to Time and Space produces a sense of the ultimate merging of physics and metaphysics in that intensely individual way of Ballard’s, where grotesque, tormented characters inhabit and reflect a bright nightmare world that is at once unreal and yet real in the sense that it totally convinces on the level of the unconscious, cutting past the defenses of the outer mind and reaching the core of the inner mind, evoking responses that the reader did not know he had and, perhaps, does not understand even as he experiences them.”

Significantly, the talented Mr. Colvin pops up again elsewhere in #154 with what perhaps could be interpreted as one of his own humble attempts to evoke similar responses in his readers - a sixteen page story named ‘The Pleasure Garden of Felipe Sagittarius’.

Described in Moorcock’s editorial as “an experimental story of a kind [Colvin] believes hasn’t been tried before and which, he says, is ‘meant to be enjoyed, not studied’”, this story actually turned out to be an extremely important turning point in Moorcock’s writing.

Beginning with the image of ‘Minos Aquilinas’, “the top Metatemporal Investigator in Europe” clambering through the war-torn ruins of an alternate-world Berlin, the story posits that murder has been committed in the unnaturally verdant garden of the city’s police chief, Otto Van Bismarck, and that Bismarck’s personal assistant, one Adolf Hitler, is up to his neck in suspicion.

Also factoring in appearances by Kurt Weill, Albert Einstein and Eva Braun, and presenting the titular Felipe Sagittarius as a cultivator of lethally hallucinogenic, erotically scented greenery, this extremely strange first person detective story may be sketchy in the extreme, but it nonetheless introduces us – possibly for the first time – to the kind of temporally/spacially unmoored dystopian vignettes that would go on to define the style of the Jerry Cornelius mythos that Moorcock unleashed a few years later, as well as prefiguring the pungent aesthetic decadence that would characterise his experimental fiction as a whole, and even hinting at the kind of perverse alternative history scenarios that would increasingly predominate in his work through the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Clearly recognising the story as a bit of a ‘skeleton key’ work in this respect, Moorcock later revised it (under his own name, natch) when he came to compile his series of “Eternal Champion” compendiums in the early 1990s, re-christening the protagonist as a member of his Von Bek dynasty and placing it in the very first volume of the series, alongside several much later novels.

Confusingly, there was also a third iteration of the story at some point, this time with the narrator identified as “Simon Begg”, but, leaving such delving into the labyrinths of Moorcock’s literary revisionism aside for now, it is certainly a thrill to see ‘The Pleasure Garden..’ appearing for the first time here, hot off the presses and straight from the young editor’s fevered brain.

*A gentleman of of widely varied talents, Edmund Crispin is probably best-known for his series of ribald comedy-mystery novels, including ‘The Moving Toyshop’ and ‘Unholy Orders’, which I can highly recommend. Wikipedia also informs me that he wrote the score for The Brides of Fu Manchu, of all things, as part of an extensive composing career under his birth name Bruce Montgomery.