Edgar Allan Poe existed in a momentary by-way of relative peace and security in a new country still full of hope, yet his work is limned by the same dark phantoms that haunt E.T.A. Hoffman’s, a writer who lived when Europe was an open field trampled by the Napoleonic Wars. The landscape of the mind does not always correspond to external circumstance. Rather, there seems to be inside us a constant, ever-present yearning for the fantastic, for the darkly mysterious, for the choked terror of the dark.”

[…]

“The superficial moralists who deplore the tendencies of certain movies to alarm them and in the same breath pretend that film is art would do better to realise that always alongside the art that pleases, ‘the Art of seduction’, springs the art of terror. Often we find pleasure in non-pleasurable forms. Next to smiling terracotta couples reclining on top of their Etruscan tombs, to whispering angels with gold-leaf wings, to ‘The Rape of the Lock’ and ‘The Marriage of Figaro’, there have always arisen hair-blanching depictions of the damned, of Saturn devouring his children, the temptations of St Anthony, ‘Wozzeck’, and Man the Wastrel lost to gorgons, dragons, destiny, and death.

Moreover, art works that stir the dregs of human experience have a steady unvarying coherence in their emblems and embodiments, while the style of patterns of perfect, healthy, happy beauty fluctuate as rapidly as fashion itself and contradict one another’s ideal forms according to period and culture. Satan is immutable, it would seem, whether ancestral dark angel or devil in the flesh. Those who imagine him today are not the doctors of demonology but the psychiatrist, the anthropologist, the sociologist. To them, horror movies might be seen as a historical imperative, if not an aesthetic necessity.”

[…]

“Still, we are expected to be terrified by the horror film, and fear, no matter how diluted or sublimated, is a very intense reaction to an experience, aesthetic of otherwise, and, failing Art, one not to be enjoyed with an easy conscience. Rather than sheer perversity, horror films require of the audience a certain sophistication, a recognition of their mystical core, a fascination of the psyche. […] What seemed to put the reviewers off horror films, what prevents them (even now) from surrendering their critical resistance, is their frequent - usually necessary - depiction of the fantastic.

This would be as superficial and absurd as dismissing Fra Angelico or Max Ernst because we don’t, or simply won’t, believe in angels and sphinxes. And yet the movies were progressing from the Manichaean simplicity of the Western - a genre that was more readily acceptable - to the Promethean ambiguity of the horror story, from start back-and-white to the nuances of the dark, from the wide open spaces to the psychic hinterland.”

Any questions? No? Good.

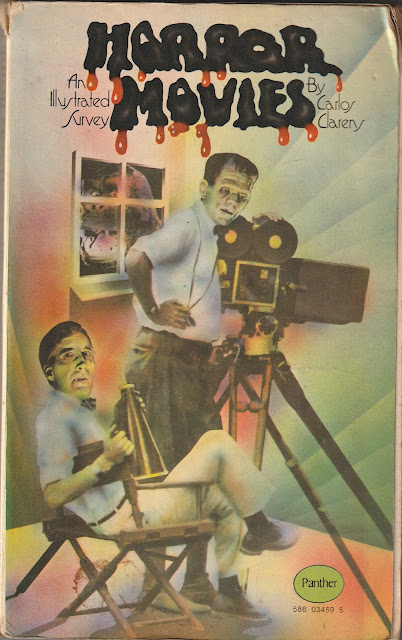

I’m aware that updates to this blog have, once again, been rather piecemeal so far this year, but rest assured - I’ve been looking forward to my October horror marathon like a storm-tossed sailor longing for shore leave, and, come hell or high water, I’m going to be offering some choice words on assorted examples of the horror genre in this space across the next 31 days.

It’s unlikely any of it will prove quite as lyrical or well turned out as Mr Clarens’ mellifluous prose above (vocab: “limned”, best phrase: “..the choked terror of the dark”), but I’ll do the best that a couple of tired sessions across the Witching Hour will allow. As always, expect insensible first draft blather, typos and weird grammar all over the joint, but I hope they won’t spoil the fun too much.

Comments and feedback, as ever, warmly received.