Monday, 29 May 2017

The Adventures of John Carpenter

in the 21st Century:

Cigarette Burns (2005)

in the 21st Century:

Cigarette Burns (2005)

After effectively clearing his desk and waving goodbye to the Hollywood rat-race following the critical and commercial failure of ‘Ghosts of Mars’ in 2001, John Carpenter’s next directorial assignment was a one hour TV movie, produced as part of the first series of the ‘Masters of Horror’ project in 2005. Subsequent to its original broadcast, ‘Cigarette Burns’ has lived on as one of the most talked about and well regarded entries in that series… although the extent to which its success can be attributed to Carpenter’s participation is debatable, as we shall go on to discuss.

Before we get to that though, Drew McWeeny and Scott Swan’s script for ‘Cigarette Burns’ is very much a “high concept” number, and a pretty great one at that, so a quick synopsis is probably in order.

Basically, the story here is nothing less than a cult movie in-joke blown up into a full-blooded piece of cosmic horror, built around what is basically a celluloid equivalent of Lovecraft’s ‘Necronomicon’ (or, more prosaically, a movie-world version of the 1999 Polanski thriller ‘The Ninth Gate’).

Our protagonist is Kirby (Norman Reedus), the proprietor of a struggling Alamo Drafthouse-style repertory cinema, who also holds a formidable reputation for tracking down elements for lost and ultra-obscure films. It is in the latter capacity that Kirby visits the home of a decadent, ultra-wealthy collector named Bellinger (played for maximum creep effect by Udo Kier), who offers him enough money to immediately write off his debts and save his cinema, if he can track down a print of one particular film.

All well and good then, but we can almost feel Kirby’s guts perform a somersault when Kier dramatically announces that the film he wishes to locate is… ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’.

The near mythic final work of a controversial (and deceased) European director named Hans Backovic, ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’ was publically screened only once, at the Sitges festival in 1969. Legend has it that people died, and blood ran in the aisles. Survivors refused to discuss what had happened in the screening room, and were never quite the same. The director’s sole print of the film was reported to have been seized by the Spanish authorities and destroyed. Or was it…?

Bellinger has of course been obsessively collecting ephemera related to ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’ (a framed poster hangs next to his priceless three-sheets for ‘Metropolis’ and ‘Nosferatu’), and the stakes are raised further when he offers to show Kirby the jewel of his collection – a living souvenir from the production that subsists in darkness, chained in his basement.

Now, if you’re anything like me, by this point the rest of this review will pretty much be moot. You will need to seek out and watch ‘Cigarette Burns’ immediately.

Ever since Lovecraft first placed the idea in my head as a teenager, I’ve loved the notion of a cultural artefact so terrible (in the literal sense of the word) that it destroys those who come into contact with it, and have always found myself totally captivated by stories along those lines.

That the ephemera surrounding weird, esoteric movies also greatly appeals to me should be no-brainer given the nature of this weblog, and I’m happy to report that, for the most part, McWeeny and Swan’s script tackles this material as well as could be wished for, mixing up just the right quantities of mystery and ambiguity, attention to detail and engrossing detective work to create a slow, creeping sense of dread and fascination around ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’, building up our anticipation of the moment when Kirby finally finds himself touching the canisters containing the reels of the film to fever pitch.

Given that this review strand focuses on John Carpenter though, we should probably divert our attention back toward his contributions, and, the first thing that will be obvious to the director’s fans is that ‘Cigarette Burns’ does not feel very much like a John Carpenter film. I’m not sure at what stage of the pre-production Carpenter became involved, but suffice to say that, beyond the actual, technical business of directing, the other distinctive touches that feed into what we think of as “a John Carpenter movie” – usually incorporating everything from the writing, to the casting, to the score – are notable by their absence.

My gut feeling is that Carpenter must have approached this one as a straight “shoot the script as written” job, and, given the strength of the material provided him by the writers and the wealth of interesting plot detail to be covered, that was probably a good call.

Nonetheless, I hate to say it, but…. I can’t help but feel that the intermittent weaknesses that compromise this otherwise excellent film could potentially be interpreted as the result of Carpenter bungling certain aspects of the script that simply presented him with situations and ideas that he was simply unable to get a proper angle on.

It’s not as if Carpenter hadn’t taken a few creditable shots at cosmic horror in the past (see ‘Prince of Darkness’ (1987) and ‘In The Mouth Of Madness’ (1994) in particular), but, whilst I like both of those films, I’ve always felt that his sensibility as a director does not really lend itself to grasping the totality of the Lovecraft/Kneale-derived stories he so obviously admires.

Caprenter’s take on things is just too, I dunno… pulpy, for want of a better word. His best films are down to earth, action-orientated, practical. At times, he has been able to conjure great power and atmospheric gravitas from Weird Tales-esque subject matter, but when more careful notes of subtlety are required, or when things start to get more cerebral, multi-layered or mind-bending, he has a tendency to (sometimes literally) lose the plot.

Thus, whilst the treatment of ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’ during the first half of ‘Cigarette Burns’ achieves an absolutely sublime level of eeriness, things become progressively more inconsistent as our protagonist gets closer to comprehending the true nature of the film-within-a-film.

Personally speaking, I found the story’s ‘angels & demons’ angle to be both tediously over-familiar and pretty poorly handled, and the film’s conclusion is also marred by the inclusion of an excruciatingly silly, sub-Fulci gore set-piece that seems to have been thrown in purely as a rather patronising attempt to keep the horror fans ‘on-side’ – but whether you wish to place the blame these minor fumbles on script, director, the producers of the series or some combination thereof is largely a moot point.

A more significant misstep comes I think when Carpenter actually begins to let us see pieces of footage from the dreaded, blasphemous reels of ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’, and – in the tradition of every film you’ve ever seen in which a character is built up as an artistic genius whilst the poor production designer is handed the thankless task of coming up with some evidence to justify this assertion – it is inevitably a bit of a let-down.

As if echoing the real life experience of soaring expectation followed by crushing let-down that frequently befalls those of us who make a habit of tracking down weird and obscure movies, the scene earlier in ‘Cigarette Burns’ in which we get to see some production stills from ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’ is almost heart-stoppingly exciting - all the more so given how closely it mirrors the feeling I’m sure we’re all familiar with, when one sees a hazily suggestive black & white still from some extraordinary, esoteric movie reproduced in a reference book and thinks, “my god, what is this movie?! I must see it!”.

It is in these moments – whilst interrogating the networks of fascination, repulsion and obsession that underlay our shared desire to seek out non-mainstream films – that ‘Cigarette Burns’ is at its strongest, finding new ways to fuse the real life interests and activities of its perceived viewers with intimations of doom-laden supernatural horror.

The moment it becomes clear however that ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’ basically just resembles some pretentious, Catholic-baiting Euro-arthouse S&M/torture flick – the kind of thing a particularly po-faced student might come up with after watching a few Borowczyk or Robbe-Grillet films - the spell is broken.

Another significant drawback arises from the fact that, whereas in his own films Carpenter has pretty much always framed his characters within a semi-fantastical, action-adventure environment, ‘Cigarette Burns’ by contrast requires him to present his protagonist’s back-story (which involves drug addiction, the death of a partner and a hefty burden of subsequent guilt and responsibility) in strictly realistic, harrowing terms.

As a result, the scenes in question are played so heavy-handedly they’re almost laughable, raising sniggers from moments in our characters’ lives that should be devastating, and botching the whole (potentially very interesting) aspect of the story wherein the power of ‘La Fin Absolue du Monde’ lies in its ability to become toxically entwined with the personal failings and guilty consciences of the individuals who become involved with it. Such an idea is, admittedly, pretty difficult to fully elucidate on screen, and I hope readers will understand that it is not necessarily a criticism of Carpenter when I say I suspect that, working under the time and budgetary constraints of a one hour TV movie, he couldn’t really make it fly.

But, I don’t want to accentuate the negative too much here. Although flawed to a certain extent, ‘Cigarette Burns’ is nonetheless a captivating and thought-provoking effort that – in direct contrast to the reassuringly familiar terrain of ‘Ghost of Mars’ – sees Carpenter casting the net of his ambitions way beyond the limits of the comfort zone he had carefully established for himself in preceding decades, producing a bold and unique horror film that, whatever your eventual take on it is, certainly stands as a ‘must see’ for anyone with an interest in cosmic horror, the culture surrounding ‘cult films’, and the potential intersection between the two.

Were it not a TV show, this would be one of those movies for which you would be well advised to book a table in advance for the post-screening discussion, which is liable to get just as involving as the movie itself. I highly recommend tracking it down, despite having just spent the best part of a thousand words griping about all things it got wrong.

Monday, 22 May 2017

The Adventures of John Carpenter

in the 21st Century:

Ghosts of Mars (2001)

in the 21st Century:

Ghosts of Mars (2001)

Strangely enough, I’d pretty sure I actually attended the UK premiere of John Carpenter’s last Proper Movie to date way back in… 2001, I’m assuming? If I recall correctly, this event took place in the inauspicious environs of Leicester’s local arts cinema, and, as a student in the city at the time, I’d snagged a season ticket to their annual Fantastic Film Fest (oft referenced here in the past), and so went along.

The reception, it must be said, seemed muted. In fact I don’t recall the atmosphere being much different to that of yr average Tuesday night movie screening. Until I re-watched it this year, I didn’t remember very much at all about the film itself, but, being at the time a rather snobbish fan of cerebral, “big idea” sci-fi and avant garde freakiness, I don’t think I liked it very much.

More fool me then, and more fool the rest of the world, who apparently joined me in consigning ‘Ghost of Mars’ to unremembered oblivion amid the millennial whirl of the early ‘00s, prompting (or at least accelerating) Carpenter’s decision to pack it in and make a tactical withdrawal from the world of mainstream filmmaking.

Returning to the film in 2017, with of fifteen years of water under the bridge, I’m sure I won’t be the only Carpenter fan to take a chance on the recent blu-ray reissue and discover that, whilst it’s certainly no lost classic, ‘Ghost of Mars’ is, in a profound sense, actually pretty good.

I mean, clearly no one is going to try to make the case for ‘Ghosts..’ as one of Carpenter’s best films, and in terms of production value it’s probably one of his least ambitious projects, but in a sense it is the very modesty of the film’s ambitions that serve to make it such an enjoyable prospect today.

Taken on its own terms as a late-VHS-era b-movie in fact, I would contend that ‘Ghost of Mars’ is rock solid, with Carpenter’s distinctive guiding hand discernable in just about every aspect of the production, from the initial concept to the final edit. So - if the idea of John Carpenter directing a rock solid late-VHS-era b-movie pleases you, hesitate no longer over that “add to basket” button, because I’m confident you’ll have a good time here.

I don’t imagine that Carpenter planned ‘Ghosts..’ as his “last hurrah”, but in retrospect the movie’s tendency to fall back on story elements retooled from ‘Assault of Precinct 13’, ‘The Fog’ and ‘The Thing’ certainly gives it a self-referential “last lap of the track” vibe that – whilst much criticised in contemporary reviews - now allows us to indulge in some pleasurable nostalgia for an era in which movies such as these actually got made.

For those of us of a certain age and inclination in fact, ‘Ghosts of Mars’s potential as rainy day comfort viewing is immense. Not only is it probably the closest Carpenter ever came to the kind of modest, Hawksian western he always claimed he really wanted to make, but, speaking as a child of ‘90s video rentals, I also found myself loving ‘Ghosts..’s production design, which resembles a kind of perfect amalgam of every mid-budget/straight to video sci-fi actioner that that decade produced.

It’s full of unfeasibly bulked up post-‘Aliens’ assault rifles, tense walks down clanking corridors, faux-tough guy posturing, infra-red “monster-vision”, cyber-punky made up drugs and set within one of those weird, brightly lit ‘Total Recall’-esque dystopian off-planet colonies that actually looks quite nice and orderly -- and, somehow, all this squares quite nicely with the kind of no nonsense script that could easily have been “Raid on Dry Gulch” or some-such in a former life.

Natasha Henstridge from the ‘Species’ movies turns in a surprisingly strong performance as our resident space-sheriff, proving beyond doubt that she had the necessary acting chops to carry this kind of movie (if only anyone had been paying attention), and, if Ice Cube sadly doesn’t make much of an impression as our Snake Plissken/Napoleon Wilson surrogate (“Desolation Williams”!), there’s no shortage of other interesting contenders to fill the vacuum, from Jason Stratham doing his latter-day cockney action man thing to Robert Carradine drivin’ the big train, Joanna Cassidy from ‘Bladerunner’ fleeing across the Martian desert in a shakily CGI-assisted hot air balloon (shades of Edgar Rice Burroughs, perhaps..?), and, how can you say no to Pam Grier as the butch dyke space police commander? (With difficulty is the answer you’re looking for.)

Given its status as an unpretentious action-adventure movie furthermore, I think some of the ideas in ‘Ghost of Mars’ aren’t half bad. Considering the kind of comic machismo, barely concealed homo-erotic sub-texts and quaintly adolescent fear of women that had long dominated Carpenter’s films by the time he made this one, the decision to make the Mars colony a matriarchy is certainly an interesting one, and, though the implications of this are never really explored in much depth, there is nonetheless an enjoyable frisson to be found in watching an action movie in which most positions of power and normative authority belong to female characters, with the men conversely portrayed as ‘plucky underdogs’ and suchlike. (I also enjoyed the way that the film’s outlaw characters sneeringly accuse each other of “workin’ for The Woman”.)

The possessed Martian miners who comprise the film’s monster-threat are pretty good too, representing a distinctive and genuinely alarming spin on what could easily have been a rather ho-hum “Indians-via-zombies” type effort. With their bodies now inhabited by the spirits (or “ghosts”, y’see) of barbaric ancient Martian warriors, the human colonists begin filing their teeth, practicing grotesque self-mutilation and forging improvised new weapons for themselves, until they resemble some goth-damaged take on a Warhammer 40,000 army, waving their war banners and hefting improbably massive multi-bladed hand weapons as they bear down upon our heroes’ encampment. Though the mall-goth type make up they favour is.. kind of strange (well, it was 2001 I suppose), this is all pretty awesome, to be honest.

Although the film’s climactic siege situation had generally been read as a rehash of ‘Assault on Precinct 13’ (Henstridge & Cube’s similarly ‘Rio Bravo’-inspired sheriff/prisoner relationship certainly suggests as much), these more visible and flamboyant antagonists really make it more of a space-age/’Road Warrior’-filtered take on a good ol’ Rourke’s Drift scenario, and Carpenter clearly had a ton of fun with this notion, even throwing in a blatant homage to ‘Zulu’ at one point as he has his survivors adopt a first rank / second rank firing strategy to take down the Martians pouring through their over-run defenses.

All in all, it is difficult for me to find anything to dislike in a film that panders to my rose-tinted ideal of John Carpenter making a sci-fi action film in 2001 quite as warmly and generously as ‘Ghosts of Mars’. Even the soundtrack, built around woefully dated layers of down-tuned nu-metal guitar, worked quite well for me this time around, with the characteristic rhythmic drive of Carpenter’s compositions adding a welcome sense of urgency and forward momentum that such candy-coated sludge often lacked in the hands of the bands who popularised this questionable sound around the turn of the century.

I don’t want to build expectations for ‘Ghosts of Mars’ up too high in the midst of all this praise however. As stated, the film is certainly no gold-plated classic, but – and this is the key point – it doesn’t intend to be. If only more 21st century productions were content to set out with such modest, genre-constrained ambitions; perhaps more would succeed in fulfilling them half as well as Carpenter does here, and perhaps as a result us long-suffering viewers might have more fun of a weekend movie night. (Just sayin’.)

Sunday, 21 May 2017

The Adventures of John Carpenter

in the 21st Century: Intro.

in the 21st Century: Intro.

On Halloween night last year, my wife and I went to see John Carpenter and his band performing live at a large London concert venue. In spite of the obvious drawbacks that come with being inside a large London concert venue, we had a pretty great time.

Mr Carpenter stood at the front of the stage behind his midi keyboard, somehow looking more youthful than he did in interview footage filmed about ten years ago, and said helpful things like “MY NAME IS JOHN CARPENTER”, and “I MAKE HORROR MOVIES”, to much applause.

Sadly there was no Coupe De Villes material (boo), no Benson, Arizona, and I’m not sure ‘Assault of Precinct 13’ really benefited from a full band arrangement with rock guitars, but no matter - basically it was great. Actually, truth be told, I probably would have deemed it ‘great’ even if J.C. had just pulled up a comfy chair and taken it easy for a couple of hours, such was the pleasure I felt merely being in the presence of such a beloved cultural figure (and especially given that he seemed to be having a grand old time with the whole “being a rock star” business).

By complete coincidence, the following six months have found us watching or re-watching every significant directorial assignment that Carpenter has completed since the turn of the millennium, so, what more of an excuse do I need to write a bit for you about these oft-overlooked late era additions to his formidable legacy?

Three posts will be forthcoming over the next couple of weeks, conveniently scheduled to cover a stretch of time I’m spending out of the country and away from the computer. Have fun while I’m gone...

Sunday, 14 May 2017

The Beach of Falesá

by Dylan Thomas

(Panther, 1966)

by Dylan Thomas

(Panther, 1966)

In honour of the fact that today is apparently International Dylan Thomas Day, I thought I’d take the opportunity to pull another recent acquisition from my ever-growing paperback mountain for your enjoyment.

Though admittedly somewhat beyond the pulp fiction remit of this blog, Dylan Thomas remains one of my favourite writers. Growing up in West Wales, I was more or less force-fed his words from a young age, but since rediscovering his work in adulthood, both his prose and poems have become very dear to me.

Nonetheless, until I stumbled upon this volume on a day-trip to Brighton last month, I was entirely unaware that this most revered of twentieth century wordsmiths had ever penned “..a sinister, spine-chilling tale of superstition, black magic and evil” set upon an “exotic and inviting” South Seas island. An instant purchase, needless to say.

In order to maintain an open mind when I get around to reading it, I have deliberately carried out no research whatsoever into the history or perceived literary value of this work, other than to note that it is a re-working of a story of the same name by Robert Louis Stevenson. Likewise, the fact that this book’s copyright originally belonged to The Hearst Corporation (1959) before moving to ‘Viking Films Inc’ in 1963 is instructive, as is the fact that it barely stretches to 120 pages, despite the use of extra-large text and frequent and over-large paragraph/chapter breaks. Should be an interesting read.

I can’t say that Panther’s cover design strikes me as very appealing however. Contrary to the note I’ve scanned above, the woman pictured on the cover is most assuredly NOT a detail from Gauguin’s ‘Aha Oe Feii?’ aka ‘Are You Jealous?’ (1892), and I can only assume that this note was mistakenly retained from an earlier edition of the book. As to where this woman’s head and shoulders actually did come from, god only knows. I suspect they probably just clipped her out of a magazine or something.

So, not exactly a classic in design terms, but in literary terms…? Well, I hope to get around to it soon, so we’ll see.

Friday, 12 May 2017

Lost 0bjects.

For the past five years or so, I have been a reader of, and contributor to, the collective blog Found 0bjects, until recently located at http://found0bjects.blogspot.com/.

Unfortunately however, it has disappeared this week – presumably deleted or (here’s hoping) removed from view by an unknown person with admin rights.

Discussions between contributors have thus far drawn a blank re: establishing what happened, but, given that the blog was still regularly visited and intermittently updated, and that it contained a huge backlog of interesting content, it seems a shame for it to have been arbitrarily terminated.

If any readers here have any further info (or mere speculation) on the condition or whereabouts of Found 0bjects therefore, please let me know via the usual channels. Any assistance would be greatly appreciated, and if it turns out someone is holding it hostage – let us know, we can talk.

Thanks for your time.

Unfortunately however, it has disappeared this week – presumably deleted or (here’s hoping) removed from view by an unknown person with admin rights.

Discussions between contributors have thus far drawn a blank re: establishing what happened, but, given that the blog was still regularly visited and intermittently updated, and that it contained a huge backlog of interesting content, it seems a shame for it to have been arbitrarily terminated.

If any readers here have any further info (or mere speculation) on the condition or whereabouts of Found 0bjects therefore, please let me know via the usual channels. Any assistance would be greatly appreciated, and if it turns out someone is holding it hostage – let us know, we can talk.

Thanks for your time.

Saturday, 6 May 2017

Soul Pulp:

Keller # 1: The Smack Man

by Nelson De Mille

(Manor Books, 1975)

Keller # 1: The Smack Man

by Nelson De Mille

(Manor Books, 1975)

Bloody hell. As if to demonstrate the scarcity of these ‘blaxploitation pulps’ in my collection, not to mention the frighteningly rabid conservatism prevalent in these ‘70s ‘men’s adventure’ series books, we’re already down to this one for our second (and thus far, final) Soul Pulp post.

Born in 1943, Nelson De Mille began writing series detective books from the mid ‘70s onward and is still writing thrillers at a prolific rate to this day.

Trying to determine exactly how many ‘Keller’ novels he turned out is however complicated by the fact that some if not all of these books seem to have first been published as outings for the author’s on-going character Joe Ryker, and were sometimes credited to his Jack Cannon pseudonym, except when they weren't. For reasons unknown, these Ryker books were then retooled as Keller books, with “Joe Keller” taking over as the protagonist.

From the late ‘80s onward, it seems that De Mille revised and republished all of these books as Ryker novels, and removed all mention of “Keller” from his bibliography, with most online sources following suit. Currently, some ‘Ryker’ books being sold on Amazon even have ‘Keller’ cover art attached to them, so… who knows. I have no idea what was going on with all that, to be honest.

Anyway, for what it’s worth, ‘The Smack Man’ usually seems to be listed as the fourth Ryker book, despite appearing here as the first Keller one.

As to the book itself…. well it seems to be yr standard trudging police procedural business, enlivened largely by frequent and bold use of expletives, detailed drug use and other such tough guy shit, with some rampant misogyny, bone-crunching violence and ugly racial stereotyping thrown in for good measure. As such, there's probably some good, cynical fun to be had here, if you're nasty enough to dig it.

For a pure dose of 1975, just check out this central card ad page and the text that surrounds it. Nice.

Labels:

1970s,

blaxploitation,

books,

crime,

hard-boiled,

Manor Books,

Nelson De Mille,

New York,

novels of violence,

pimps,

pulp fiction,

Soul Pulp,

thug cops

Tuesday, 2 May 2017

Soul Pulp:

Superspade # 2: Black is Beautiful

by B.B. Johnson

(Paperback Library, 1970)

Superspade # 2: Black is Beautiful

by B.B. Johnson

(Paperback Library, 1970)

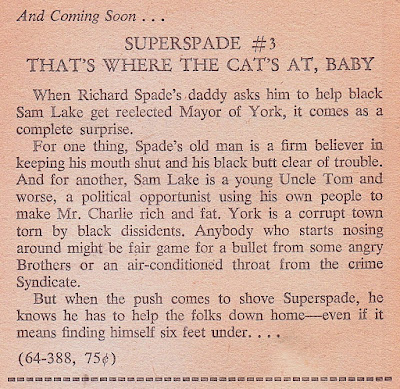

As our previous post here touched upon the sparks that flew when the aesthetic of the early ‘70s ‘black action film’ hit the literary world, I thought I might as well pull a few choice volumes off the shelf and instigate a (sadly very short) mini-series looking at what I suppose we’re contractually obliged to term “blaxploitation pulp fiction”.

First up then, we’ve got one of my favourite recent finds, and to begin with a quick note on the cover art - I wash my hands of even trying to find an art credit for this one, but I quite like the effect the artist has created by leaving most of the secondary figures as pencil sketches, just filling in (presumably) the main protagonist and antagonist.

This gives it a kind of dynamism that sets it apart from yr average example of this early ‘70s ‘action collage’ style, although whether we should treat this as the result of deliberate artistic intent or merely “we need this at the printers by Friday goddamnit, put the fucking brush down and gimme what you got so far”, I will leave to your discretion.

Moving on the the book itself, it is notable I think that it appeared in the same year that the movie version of ‘Cotton Comes To Harlem’ set about gently lampooning the Black Power movement.

The Black Panther Party, needless to say, had been big news in the U.S.A. in 1969, with the organisation’s membership reaching an all time high and Panther-related violence making waves in Chicago, New York and L.A. Bobby Seale meanwhile was under arrest charged with ordering the murder of a suspected police informant, and December saw Fred Hampton gunned down in an exchange of fire with cops in Chicago.

Clearly the editors at Paperback Library wasted no time in exploiting the publicity surrounding these events to the max, and the enigmatic B.B. Johnson knocked out no less than five ‘Superspade’ novels for them in 1970, with one further book following in ’71.

Like Ossie Davis’s aforementioned movie, ‘Black is Beautiful’ obviously takes a pretty cynical view of Black Power, skirting the fringes of libel (“Ridge Hatchett”? - c’mon) as it “exposes” the allegedly self-serving con men behind the revolutionary rhetoric.

At least Davis (and Chester Himes before him) had the advantage of actually being black when they expressed such opinions however; though Paperback Library may have dug up the coolest author photo in recorded history for “B.B. Johnson”, I will eat my neckerchief if the individual behind these books was actually a gentleman of colour.

Skim reading a few chapters of ‘Black is Beautiful’ in fact, the authorial voice seems more suggestive of a middle-aged, white divorcee typewriter jockey mopping his brow with a gingham handkerchief in a back office somewhere, scouring the local black community paper to try to get the right lingo down whilst cursing his editors for not just letting him do another Bond rip-off. (The book eventually runs with the idea that the Panthers – sorry, ‘Jaguars’ – are a front for Castro’s Cuba incidentally, which puts my hypothetical author back on the more familiar ground of good ol' anti-commie paranoia.)

But, who am I to make such assumptions? Prove me wrong if you dare, and if it turns out ‘Superspade’ actually WAS a side-gig for Melvin Van Peebles or Isaac Hayes or somebody, I’ll be on neckerchief sandwiches all week.

Either way, I fear this book is no classic, but its value as a cultural artefact is mighty indeed.

First up then, we’ve got one of my favourite recent finds, and to begin with a quick note on the cover art - I wash my hands of even trying to find an art credit for this one, but I quite like the effect the artist has created by leaving most of the secondary figures as pencil sketches, just filling in (presumably) the main protagonist and antagonist.

This gives it a kind of dynamism that sets it apart from yr average example of this early ‘70s ‘action collage’ style, although whether we should treat this as the result of deliberate artistic intent or merely “we need this at the printers by Friday goddamnit, put the fucking brush down and gimme what you got so far”, I will leave to your discretion.

Moving on the the book itself, it is notable I think that it appeared in the same year that the movie version of ‘Cotton Comes To Harlem’ set about gently lampooning the Black Power movement.

The Black Panther Party, needless to say, had been big news in the U.S.A. in 1969, with the organisation’s membership reaching an all time high and Panther-related violence making waves in Chicago, New York and L.A. Bobby Seale meanwhile was under arrest charged with ordering the murder of a suspected police informant, and December saw Fred Hampton gunned down in an exchange of fire with cops in Chicago.

Clearly the editors at Paperback Library wasted no time in exploiting the publicity surrounding these events to the max, and the enigmatic B.B. Johnson knocked out no less than five ‘Superspade’ novels for them in 1970, with one further book following in ’71.

Like Ossie Davis’s aforementioned movie, ‘Black is Beautiful’ obviously takes a pretty cynical view of Black Power, skirting the fringes of libel (“Ridge Hatchett”? - c’mon) as it “exposes” the allegedly self-serving con men behind the revolutionary rhetoric.

At least Davis (and Chester Himes before him) had the advantage of actually being black when they expressed such opinions however; though Paperback Library may have dug up the coolest author photo in recorded history for “B.B. Johnson”, I will eat my neckerchief if the individual behind these books was actually a gentleman of colour.

Skim reading a few chapters of ‘Black is Beautiful’ in fact, the authorial voice seems more suggestive of a middle-aged, white divorcee typewriter jockey mopping his brow with a gingham handkerchief in a back office somewhere, scouring the local black community paper to try to get the right lingo down whilst cursing his editors for not just letting him do another Bond rip-off. (The book eventually runs with the idea that the Panthers – sorry, ‘Jaguars’ – are a front for Castro’s Cuba incidentally, which puts my hypothetical author back on the more familiar ground of good ol' anti-commie paranoia.)

But, who am I to make such assumptions? Prove me wrong if you dare, and if it turns out ‘Superspade’ actually WAS a side-gig for Melvin Van Peebles or Isaac Hayes or somebody, I’ll be on neckerchief sandwiches all week.

Either way, I fear this book is no classic, but its value as a cultural artefact is mighty indeed.

Labels:

1970s,

action,

B.B. Johnson,

Black Panthers,

blaxploitation,

books,

crime,

Paperback Library,

pulp fiction,

Soul Pulp

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)