There are few things in life I enjoy more than a mid-week Krimi. Settling down with a glass of single malt to savour the delights of ‘Monk with a Whip’, aka ‘The College Girl Murders’, whilst my neighbours presumably content themselves with whatever Netflix or Mouse Plus have to offer, I can’t help but feel I’m “living my best life”, as the kids might put it.

By 1967, it’s safe to say, Rialto Films’ prolific series of German language Edgar Wallace adaptations had already lived their best lives many times over. But, even as the well-worn formula began to look a little ragged around the edges, both the introduction of colour and the gradual retreat of censorship through the second half of the ‘60s helped the ‘krimi’ experience something of a second wind, and happily, ‘Der Mönch mit der Peitsche’ (as it was known to West German audiences) stands out as one of the prime beneficiaries of these developments.

Although the film is allegedly adapted from Wallace’s 1929 novel ‘The Terror’, by this point Rialto’s scriptwriters were no longer even pretending to tell a coherent mystery story. Instead, ‘Monk..’ foregrounds a startling succession of outrageous, mildly titillating pulp / comic book set-pieces, loosely tied together into a distinctly half-hearted whodunit narrative, the resolution of which singularly fails to address the questions raised by the improbable events which have preceded it. Which is fine by me, needless to say - the crazier these movies get, the better, so far as I’m concerned.

As such, the film begins in a mouldering Frankensteinian laboratory located beneath a fog-shrouded gothic church (elaborate beakers and test tubes full of bubbling, fluorescent potions present and correct), wherein an elderly, white-haired scientist has perfected a colourless, odourless poison gas. As he merrily demonstrates, this can achieve the frankly less than earth-shattering result of killing a bunch of mice in a matter of seconds. (Is it just me, or does this feel like pretty uncomfortable subject matter for a post-war German film? Let’s not even go there, shall we.)

Keen to test his invention out on a human subject, the amoral egghead orders his reluctant assistant to enter the new formula in the book in which they apparently record such things. But, as the assistant opens the book’s cover - boom! - the crazy doc has only gone and installed a miniaturised poison gas spray it! Down goes the assistant, cackle-cackle goes the prof.

Cue the reverb-drenched voice of “Edgar Wallace”, the obligatory blood-dripping crimson titles, and the explosion of a main title theme, which, though it is not on this occasion composed by primo Krimi maestro Peter Thomas, nonetheless provides a pretty good imitation of the squawking, lurching tones of his deeply eccentric psyche/jazz/exotica stylings. (Martin Böttcher, who handled pretty much all the key krimis not scored by Thomas, was the man responsible.)

Clearly intent on wringing some immediate profit from his dastardly invention, we next see the scientist above ground amidst the tombstones, where he hands over a poison-loaded prayer book and a suitcase full of other nefarious, gas-related goodies to an unseen criminal, who arrives in a chauffeured Rolls Royce. The doc doesn’t have long to gloat however, as - ka-pow! - he suddenly finds himself garrotted by the lasso-like whip wielded by a hulking ‘monk’ clad in bright red robes and a conical KKK hood! Ye gods.

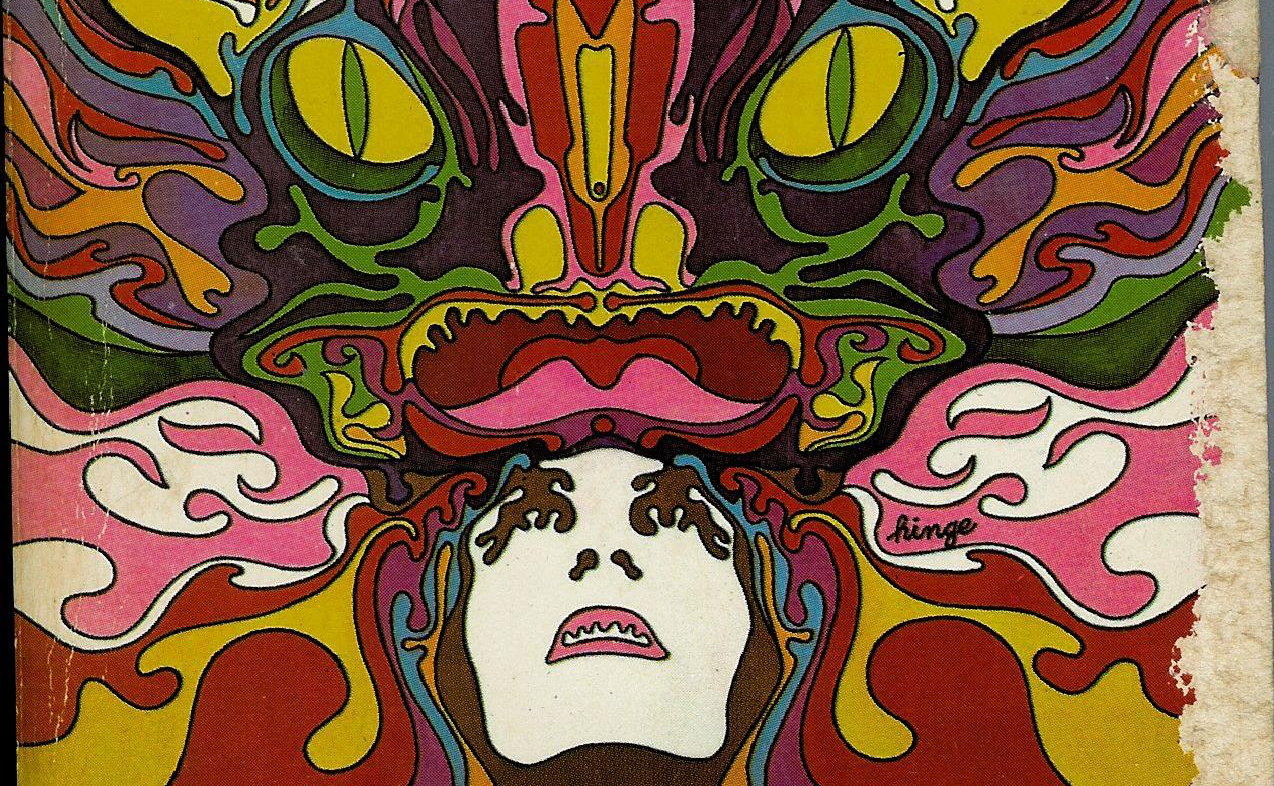

It would be difficult for any movie to top the EC Comics-via-Mario Bava ghoulishness of this opening, but ‘Monk with a Whip’ keeps the motor running for its next, loosely connected, segment, which concerns a prison inmate who is sprung from the joint, only to find himself transported (blindfolded of course) to the lair of a Dr Mabuse-like super-criminal, who sits with his back to the interviewee, his voice seemingly booming from the walls of a darkened, wood-panelled aquarium, from which giant turtles, manta rays and suchlike cast eerie, green-tinted shadows.

(The antechamber the villain’s lair, lest I forget to mention it elsewhere, comprises a rickety indoor rope bridge over an artificial swamp populated by alligators and pythons!)

Equipped with the deadly prayer book seen in the earlier sequence, the prisoner is promised riches in exchange for assassinating - for no reason which is ever satisfactorily explained - a suspiciously mature looking pupil at a Catholic girls’ school. (“FINALLY,” exclaim the audience who tuned in for ‘The College Girl Murders’.)

It is the demise of this unfortunate young lady which attracts the attentions of Scotland Yard, and in particular, the indefatigable Sir John, played as always by Siegfried Schürenberg. “What will they try next?”, he exclaims, throwing down a report on the killing, before calling in our old friend Joachim Fuchsberger (here playing one Inspektor Higgins), who, as a veteran of both The Black Abbott and ‘The Sinister Monk’ (1965), should surely be well-qualified to get to grips with this particular case.

A cameo player in the earlier films in series, Sir John was usually found choking on his tea in response to Fuchsberger’s mod-ish behaviour, but here he finds himself promoted to a central character - essentially subbing for mercifully absent comic relief overlord Eddi Arent, as he goes out ‘in the field’ to assist Higgins with the investigation.Sir John’s shtick here concerns his attempts to prove the value of the new, “psychological” detection techniques in which he has apparently received some training - a one joke set up which, sad to say, soon becomes quite tiresome, as he bumbles around making a fuss about the psychoanalytical significance of witnesses’ testimony and so on, all whilst Fuchsberger smiles indulgently in the background.

This does lead to one genuinely amusing moment, when Sir John declares that he will rush home and consult his reference books to ascertain the potent Freudian implications of a dormitory full of school girls experiencing a collective hallucination of a red-clad monk, only for Fuchsberger - who, as noted, has form in this area - to gently reassure him that, “they say they saw a monk because there was a monk”.

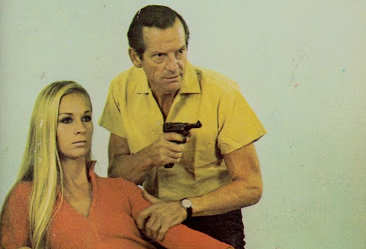

That aside though, I confess that the Scotland Yard elements of ‘Monk with a Whip’ didn't quite hit the mark for me. Fuchsberger in particular seems a bit tired here, both as an actor and a character. Lacking much of the ‘silver fox’ charisma he brought to earlier adventures, he is more of a straight up, down-at-heel detective in this one. Despite some token attempts at flirtatious banter with Sir John’s Moneypenny-ish secretary (played on this occasion by Ilse Pagé), the unlikely depiction of Scotland Yard as a kind of louche bachelor’s paradise, as seen in films like 1964’s Der Hexer, seems to have diminished considerably by this point.

Likewise, as per The Hunchback of Soho, this one comes up disappointingly short on the kind of incongruous, not-quite-right English detail we UK-dwellers love to chuckle at in these films. Set largely in anonymous rural locations, there is perhaps a sense here of the Rialto films attempting to increase their international appeal (foreshadowing perhaps the reliance on questionable co-production deals which would just about keep the Krimi brand on life support into the early ‘70s).

Changes were also clearly afoot in terms of casting, with few holdovers here from the ‘krimi gang’ who helped fill Rialto’s black & white era films with such a memorable gallery of rogues and red herrings - but, despite all this, if we can cease comparing ‘Monk with a Whip’ to earlier krimis for a few minutes, there is so much else to love here.

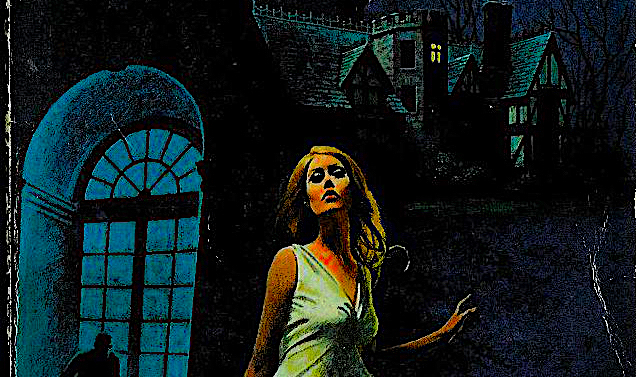

Primarily, the film’s lighting and production design - though evidently executed on a tight budget - is really rather wonderful. Nocturnal scenes (of which there are many) fare particularly well in this respect, as DP Karl Löb (who appears to have handled photography on the vast majority of ‘60s German cult films) intersperses fields of dark shadow and deep, mossy greens with occasional outbursts of searing primary colour - not least the crimson-clad monk himself - whilst the smoke machines are meanwhile working overtime, lending a bit of a ‘Blood & Black Lace’ vibe to proceedings; ‘60s pop cinema in excelsis.

Throughout the film in fact, colours are cranked up to an admirably extreme level of saturation; all of the female characters wear eye-popping, monochromatic dresses and swimsuits, whilst many of the sets find a way to glow with some kind of eerie phosphorescence or another, like a wild, candy-coloured riposte to the cheaper, more naturalistic brown n’ beige mundanity which begins to predominate during the less imaginatively shot interior dialogue sequences.

Director Alfred Vohrer may not manage to include quite so many of the baroque props or forced perspective / model-based trick shots which became his trademark (“Vohrer-isms” as I recently heard them described in the Projection Booth podcast’s Krimi episode), but he nonetheless does everything in his power to keep the film visually exciting.

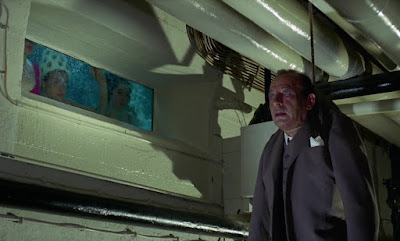

In particular, Vohrer gets much mileage out of the scenes set in and around around the school’s swimming pool, which, inexplicably, includes a kind of ‘viewing window’ in the service area beneath the pool, allowing for a number of unusual/distorted shot compositions. (How exactly this airy, modern building fits in with the ancient gothic exteriors we see representing the school’s estate is anyone’s guess, but no matter.)

It is here that the film’s perpetually sweaty pervert science teacher character (played by Konrad Georg) likes to crouch, watching the bathing beauties swim by - but, the teacher’s voyeurism goes both ways, as, in one of the films best moments, the young heroine Ann (Uschi Glas) dives into the pool, and, gazing out through the submerged viewing window, spies the hanging corpse of the sweaty teacher, ironically deposited in his favourite peeping spot by the monk.

As such incidents suggest, there is still a strong undercurrent of macabre sordidness running through ‘Monk with a Whip, however light-hearted and campy things may become at times. As well as sweaty Konrad, characters like the shifty-eyed headmistress (Tilly Lauenstein) and menacing chauffeur (Günter Meisner) bring some fresh blood (so to speak) to the movie’s unwholesome ID parade of suspects, whilst the idea of the school’s pupils leaving the safety of their dormitories to ‘party’ in the red-lit lodge occupied by a shady writer and sundry leery teachers is also fleetingly explored.

Momentarily reminding me of 1962’s somewhat krimi-influenced Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory, this notion of lonely girls leaving the safety of their collective lodgings to drift into the dark woods, in search of illicit thrills, remains a potent addition to the mystery, and, though it is never fully developed here, we do at least get a nice piece of ‘Twin Peaks’-ish noir jazz to set the mood.

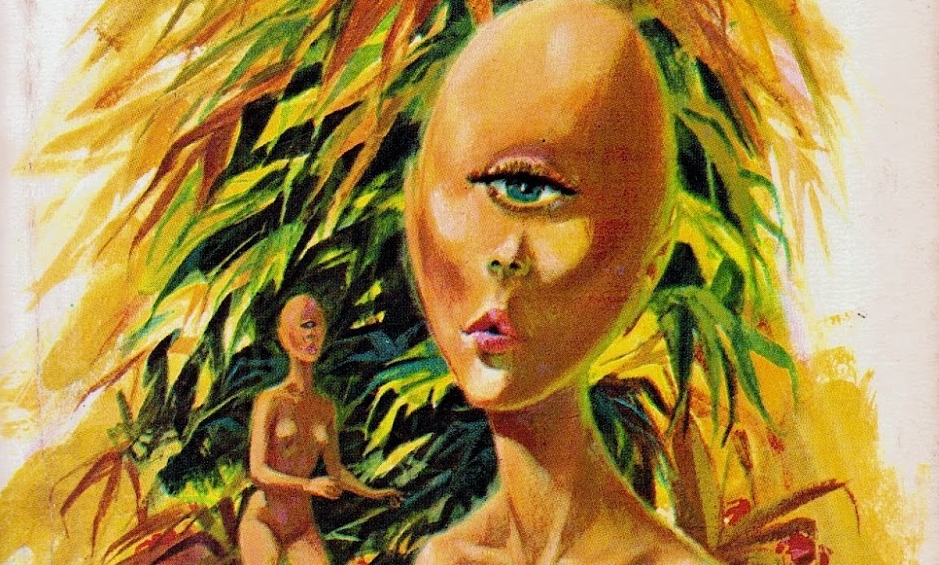

Then of course, there’s the whip-wielding monk itself - such a wonderfully absurd, surrealistic creation! Seemingly pulled straight off the cover of some especially depraved fumetti, it’s enough to make you forget that this was somehow at least the third film Rialto managed to make about malevolent masked clerics knocking people off in the dead of night before being subjected to an inevitable, ‘Scooby-Doo’-esque unmasking.

(If the plot is not complicated by at least one instance of an innocent character dressing up as the monk, or an unconscious hero being left lying around in monk robes, or multiple monks, or something, I believe you’re allowed to ask for your money back.)

As to that whole business with the odourless/colourless poison gas meanwhile, well, given that by the second half of the film the villains have been reduced to loading it into guns and squirting it into their victims’ faces, leaving a thick layer of fake cobwebs, I’m not really sure what advantage it holds over just, say, shooting people, especially given that the same criminal cartel employs a crimson-clad maniac with a lasso, but…. there I go with that pesky ‘logic’ again. It all adds to the fun, and boosts the body count - which at the end of the day is very much the point here.

I mean, let’s face it, but the time we account for Not-Dr Mabuse in his study / aquarium, with his snakes and crocodiles, and eerie florescent lighting, we’re pretty far gone into the realm of euro-cult delirium and - in my case at least - enjoying it all immensely.

As noted, the eventual ‘resolution’ to this mystery proves a complete damp squib, doing very little to rationalise any of the preceding carnage and leaving us essentially non-plussed as to why any of this madness really needed to happen, but at the end of the day - so what.

So long as that bloody monk gets his comeuppance and Higgins and Sir John can head back to the Yard in one piece for a pot of tea and some banter with the girls in the typing pool, all will be right with the world. As the nation’s foremost experts in the field of crimes involving girls’ schools, poison gas, secret passages, crocodiles and/or evil monks (we get a lot of that sort of thing in the home counties, don't you know), I’d like to think they have a long and rewarding career ahead of them - in my dreams, if nowhere else.