Before he went on to establish himself as one of the directors most closely associated with the ‘noir’ aesthetic via ‘The Killers’ (1946), ‘Criss-Cross’ (1948) and ‘Cry of the City’ (1949), German émigré Robert Siodmak’s first dip in dark waters of the retrospectively defined genre slipped out fairly quietly from Universal’s cash-strapped war-time production line in January 1944, lost in the shuffle to some extent, even as it managed to beat such first wave Film Noir landmarks as Wilder’s

Double Indemnity, Preminger’s ‘Laura’ and Dmytryk’s ‘Murder, My Sweet’ to the screen by a few months.

Though ‘Phantom Lady’ stands as quintessential Film Noir in terms of its maniacal, pulpy tone, pungent urban atmospherics and brooding cinematography, it is nonetheless easy to see why it has been somewhat overlooked by critics and academics in comparison to those aforementioned, textbook-ready trendsetters. Despite the fact that its story originally emerged from the none-more-noir typewriter of Cornell Woolrich, this one is an odd duck in the line-up, to say the least.

With no femme fatale figure, no doomed ruminations on masculine guilt and no spectre of implacable fate hanging darkly over its characters, those who insist on defining the genre purely in terms of its story elements and underlying thematics will likely have a hard time explaining why ‘Phantom Lady’ even

is noir, even as the film’s overall ‘feel’ screams it to the rafters.

In terms of its script in fact, this is really more of an audience-friendly mystery/suspense joint, despite traces of the characteristic pessimism underlying Woolrich’s plotting. In trying to account for this, we’re perhaps best to zero straight in on the contribution of associate producer Joan Harrison, a key collaborator of Alfred Hitchcock throughout the 1930s who followed him to Hollywood, overseeing the scripts for his early American films and gaining a coveted co-writing credit on several of them.

At this point in her career, Harrison had managed to negotiate her own contract as a producer for Universal, and ‘Phantom Lady’ became her first project in this capacity. Most sources seem to agree that it was Harrison was primarily responsible for adapting Woolrich’s book for the screen (despite the on-screen credit going to Bernard C. Schoenfeld), and if we view the film with the Hitchcock connection in mind, then, BINGO, everything falls into place.

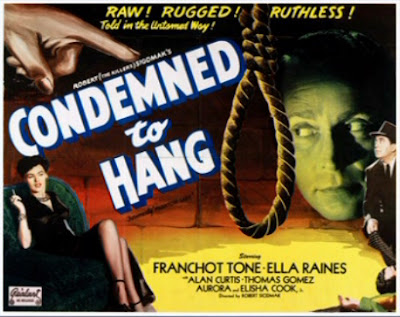

Basically, ‘Phantom Lady’ splits protagonist duties between a sympathetic ‘wrong man’ (New York architect Scott Henderson, played by Alan Curtis) racing to prove himself innocent of his wife’s murder, and his loyal ‘girl Friday’ secretary (Carol ‘Kansas’ Richman, played by the striking Ella Raines), who continues sleuthing around trying to clear her boss’s name after he’s been sent down by the judge, going to increasingly extreme lengths to try to locate the titular “phantom lady” in whose company Henderson insists he spent the evening of the murder. Chief clue, or dare we say, ‘macguffin’: the ostentatious, one-of-a-kind hat the lady in question was wearing at the time.

In a quote-unquote ‘true’ noir, this set-up would soon have veered toward the dark side of the street. If not murder, Henderson would sure as hell be guilty of

something – a ruined shell of man, tormented by the shadow of his implied infidelities and marital cruelty, likely as not – whilst Richman, for her part, would almost certainly have been coded as having an affair with her boss

before Mrs Henderson kicked the bucket, casting heavy shade on the purity of her own motives.

None of this is explored here however, as Raines’ character keeps her infatuation with blame-free nice guy Mr Henderson primly under wraps until it can be safely revealed in the final reel, and Harrison’s script instead keeps things determinedly light and linear, prioritising logical plot progression, casual wit and forward momentum over introspection or moral ambiguity.

In other words, it’s exactly the kind of story one could imagine her prepping for Hitch – a breezy, engrossing yarn in which a pair of relatable, good-natured characters race against time to solve an inscrutable, clue-laden mystery, leavened with just a touch of macabre ghoulishness (the film’s initially unseen antagonist is a rampant necktie strangler, predating ‘Frenzy’ by three decades).

Siodmak may well have had his own ideas on how best to approach this material, but for the most part, he serves his producer’s vision well here. As with many of the director’s later films, ‘Phantom Lady’ sets out its stall as an exercise in stylish, efficient movie-making, offering up a few dutch angles, deep focus shots and smooth, gliding camera moves to keep us on our toes, before unexpectedly transitioning into stretches of breathless, almost overpowering, gothic / expressionistic pulp beauty, realised with a mastery guaranteed to knock even the most jaded of cineastes off their straight-backed chairs.

The first of ‘Phantom Lady’s two real stand-out ‘bits’ is a narratively inconsequential sequence which see Raines’ character tailing a desultory bartender (a great turn from veteran character actor Andrew Tombes) as he travels home across the city after shutting up shop at 4am on the dot. A classic, leisurely paced pursuit sequence of the kind we’d go on to see time after time in later crime movies, these few short scenes become a tour de force for both DP Woody Bredell and the film’s production team, showcasing a shadow-haunted back-lot recreation of nocturnal New York whose atmospheric depth and level of detail is pretty jaw-dropping.

Like just about all Hollywood movies of this vintage, ‘Phantom Lady’s street scenes were entirely confined to a sound stage, judiciously enhanced by some theatrical backdrops and stunning matte effects, but when Raines creeps her way up the creaky stairs to an El-Train station in pursuit of Tombes, and as they stand huddled on opposite ends of the freezing platform, eyeballing each other suspiciously until the train shudders into view, it’s almost impossible to believe we’re not traversing the same location used so memorably by Friedkin in ‘The French Connection’ nearly three decades later.

And, when they step off the train a few short minutes later, the mainline hit of raw, set-bound visual poetry Siodmak gives us is just immense; the steam rising from the sidewalk, the bums playing dice on the corner, the hypnotic, ever-present flash of neon, all culminating in an economically staged, off-screen hit-and-run, rendered with just a screech of tyres on the soundtrack, and someone flinging Tombes’ hat back into frame! If this ain’t Film Noir, I don’t know what is.

Actually, the presentation – or lack thereof – of violence and death in ‘Phantom Lady’ is interestingly handled throughout. Although it essentially concerns the exploits of a serial killer, and includes a body count to rival that of any ‘40s thriller, the film maintains an almost obsequious adherence to the Production Code, pushing absolutely everything off-screen. Each time though, Siodmak (I’m assuming) manages to include some kind of gut-wrenching detail to help make these invisible events real and upsetting for the viewer; witness for instance the grief-stricken Curtis berating the off-screen ambulance crew for apparently dragging his wife’s hair across the floor(!) as they remove her corpse from his apartment; brutal.

The real highlight of the movie however is ten or so minutes we get to spend in the company of everyone’s favourite natural born loser, the one and only Elisha Cook Jr, who enjoys one of his best ever roles here, playing the keen-eyed drummer in the band at the theatrical revue Curtis and his “phantom lady” attended during their ill-fated night out together.

Functioning almost as a kind of stand-alone short film, and featuring a wilder, more exuberant visual style than much of the material that surrounds it, Cook’s sub-plot finds him absolutely not believing his luck when Raines, sexily dolled up in black as a ‘bandrat’, or whatever the appropriate ‘40s synonym for ‘groupie’ is, comes on to him as he clocks out from his theatre gig, as part of an unlikely ruse to try to pump him for information.

Playing a brasher, more confident character than he was usually allowed to, Cook initially seems to be flying about fifty feet high in some bout of pre-coital amphetamine fury here (“stick with me snooks, I’ll buy you a whole carload of hats,” he tells Raines at one point), and it’s an amazing thing to witness. As he leads her through the shadowed back streets to a darkened doorway, through which muffled music can be heard, we’re expecting of course to be ushered into some dingy nightclub or basement bar, but no - when the door swings open, to our surprise, the musicians are way up close, as is the back wall.

Yes, it’s an after-hours rehearsal room jam session, half a dozen amped up hep-cats wailing away, sound bouncing off the brick, with just a low table covered in half empty liquor bottles providing a focus in the centre, and it is likewise magnificent. Chaotically framed by Siodmak and beautifully shot by Bredell, it is one of the rawest and most intoxicating musical sequences I’ve ever seen in a movie of this vintage, all the more so once the performance reaches what I’ve read several reviewers straight-facedly describe as Cook’s “erotic drum solo” – but really, what else could you possibly call it?

With his eyes bulging from their sockets, his gap-toothed grin looking as if it’s about to consume the rest of his face, Cook frenziedly beats his pagan skins whilst leering at Raines like some Big Daddy Roth cartoon come to life – an astonishing outburst of full tilt craziness from an actor most of us will remember for so expertly portraying the walking embodiment of the word “pathetic” across five decades of American film.

It’s all the more remarkable in fact given that Cook is able to segue straight back into his more familiar ‘fall guy’ persona when, after Raines inevitably gives him the slip, he returns to his apartment to find the Mad Strangler (top-billed Franchot Tone, making his first appearance in the film) waiting in for him in the darkness, his sinister, serial killer monologue all prepared.

“Oh, how interesting a pair of hands can be,” Tone reflects, staring at his appropriately massive mitts as Cook cowers before him, that unique combination of pride and outright terror dancing across his face. “They can trick melody out of a piano keyboard, they can mold beauty out of a piece of common clay, they can bring life back to a dying child. Yes, a pair of hands can do inconceivable good. Yet the same pair of hands can do terrible evil. They can destroy, whip, torture, even kill. I wish I didn't have to use my hands to hurt another human being…”.

So long, Elisha, it’s been nice knowing you.

Such is the ability of this film’s Woolrich-derived plotting to continually knock us off balance, twisting the story’s seemingly relentless linear through-line to pull the rug from under us, evoking a sense of ‘mystery’ that puts me in mind, not so much of Hitchcock, but of the weirder end of French crime fiction with which his influence cross-pollinated via the auspices of ‘Vertigo’ and ‘Les Diaboliques’ originators Boileau-Narcejac.

We can see this early on, immediately following Curtis’s evening out with the “phantom lady”. All we know of his character as this point is that he’s a seemingly carefree man-about-town who picked up a woman in a bar and took her to the theatre, but when he returns home to his cozy apartment, he, and we, are suddenly confronted with a coterie of almost surreally grotesque police detectives holding court in his living room, primed to give him a hard time. For a few moments, we’re completely disorientated, before being left to digest the news that a) this guy is

married, and b) his wife is

dead, all in a matter of seconds.

Subsequently, Woolrich’s touch can also perhaps be discerned in the way the film stretches the real world feasibility of its tale gossamer thin, to the point where we find ourselves almost prepared to believe there must be a supernatural explanation for the seemingly impossible (at the very least, Kafka-esque) series of events our unfortunate protagonist finds himself faced with.

Could this “phantom lady” have been an

actual phantom, we’re momentarily inclined to wonder, as the police do the rounds of potential witnesses with a bedraggled Curtis in tow, only to hear a bartender and cab driver both confirm unequivocally that he was

alone during his big night out. (The subsequent revelation that these witnesses have merely been bribed by the seemingly omniscient villain of the piece meanwhile snaps us back to reality with a sadistic glee that ‘Fantomas’ authors Marcel Allain & Pierre Souvestre would surely have appreciated.)

Some may find the more elaborate contrivances of ‘Phantom Lady’s script bit clunky, but approach it in the right frame of mind and Siodmak’s careful pacing and command of dramatic atmospherics will help ensure that the unlikely twists and revelations of the film’s second half hit home in an appropriately macabre, pulpy fashion.

Sadly however, the movie significantly loosens its grip on our collective throats during the final reel, wherein an emotionally weightless, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it conclusion to the drama is followed up by a pat happy ending which feels contrived and smug in the extreme, making us feel foolish for having been so engrossed in the action of the preceding 70 minutes.

If this sappy ending feels tagged on, well, that’s because it was. As with so many ‘40s studio productions, studio-mandated re-shoots were apparently inserted at the last minute before release – a decision which is reported to have enraged Joan Harrison to the extent that she resigned from her newly minted position at Universal on the spot, refusing to return to work for the studio for a number of years.

In truth, I don’t think there is any reason to believe that the film’s original ending would have been significantly darker or more ambiguous than the one we’ve been left with, but at the same time, I have little doubt that the footage signed off by Siodmak and Henderson would have at least sold us on the Hitchcock-ian happy ending a lot more successfully than the the studio’s bland and blundering amendments.

(As it is, you can almost pinpoint the moment when the original footage gives way to the reshoots – when Thomas Gomez’s detective character inexplicably barges through the door of the killer’s apartment to rescue Raines from his clutches would be my guess.)

For the most part however, ‘Phantom Lady’ is fantastically rewarding viewing – a resolutely hard-boiled, richly evocative and deeply eccentric production that does a pretty fair job of embodying everything I love about lower budget ‘40s Hollywood noir, whilst at the same time providing tons of uproarious, earthy fun.

True, there’s not a lot of psychological depth to explore here, and the tight-knit mystery plotting allows for precious little blurring of the tale’s rather arbitrary moral black & whites, but even if this rubs you up the wrong way, the nocturnal New York and Elisha Cook Jr sequences raise the movie to a whole other level – flat-out incredible films-within-films that cement ‘Phantom Lady’s status as essential viewing for all noir aficionados.

---