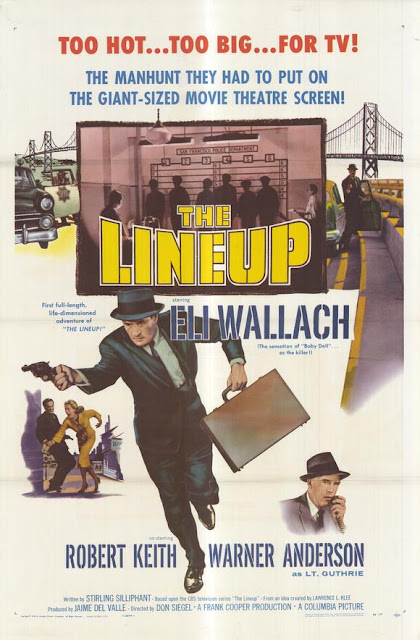

Following the lead of the film itself, let’s start off here by getting the boring bit out of the way: Don Siegel’s ‘The Lineup’ is, technically speaking, a TV spin-off.

Also known as ‘San Francisco Beat’, ‘The Lineup’ began as a radio drama in 1950 before moving to TV via the auspices of CBS in 1953. Generally viewed as a close competitor to Jack Webb’s more successful ‘Dragnet’, the show followed basically the same formula, following the day-to-day crime-fighting travails of straight-laced SFPD detective Lieutenant Ben Guthrie (played by Warner Anderson, who here resembles a somewhat older, less physically intimidating Lee Marvin), with Tom Tully (mysteriously absent from the movie version) as his partner, Sergeant Matt Grebb.

Over a decade since Jules Dassin initially kick-started the trend for cross-breeding Film Noir tropes with shot-on-location / faux-documentary police procedural stuff in 1947’s ‘The Naked City’, it’s safe to assume that movie-goers knew the drill pretty well by this point, and one can only imagine that yet another based-on-the-hit-TV-series trudge through the same good-solid-detective-work, ‘crime doesn’t play’ type palaver didn’t exactly sound too thrilling.

Assigned director Don Siegel and screenwriter Stirling Silliphant apparently agreed. After Silliphant knocked out a script which the pair both saw as the basis for an exciting, unconventional crime movie, Siegel claims that he pleaded with producers Frank Cooper and Jaime Del Valle for the opportunity to extract the movie from the ‘Lineup’ brand and let it stand alone as its own thing - but no dice. Although Cooper & Del Valle apparently didn’t give much of a damn how the film actually turned out, a ‘Lineup’ movie had been promised, and a ‘Lineup’ movie was going to be delivered.

Needless to say, Siegel and Silliphant responded to this decision by essentially pulling the same audacious bait and switch on their audience that Robert Aldrich and A.I. Bezzerides had laid on fans of Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer novels a few years earlier with their extraordinary and iconoclastic ‘Kiss Me Deadly’ (1956).

Doing little to hide their disdain for the franchise they were ostensibly working within, the director and screenwriter proceeded to entirely side-line the familiar certainties that viewers of the TV show might have been expecting, largely confining the obligatory police procedural segments to the opening twenty minutes, and pointedly relegating the show’s star Warner Anderson to the bottom of the on-screen cast list.

Meanwhile, they proceeded to kick up a veritable sandstorm of darker, more challenging and just plain weirder material, resulting in a movie which, a few decades after the dust had settled, began to gain recognition as one of the most startling and forward-thinking American crime films of its era.

Right out of the gate, Siegel’s take on ‘The Lineup’ plunges us into chaos. Out of control automobiles screech around the Embarcdaero in San Francisco’s port district, as suitcases are flung around, incomprehensible yells are exchanged and a police officer is callously mown down by a speeding taxi before the driver takes a bullet in the back and careers into the side of a jack-knifed truck. When Guthrie and his surrogate partner Quine (played by frankly terrifying tough guy actor Emile Meyer) dutifully arrive on the scene to assess the damage, all they can do is despairingly ask, “why?!” (1)Twenty minutes or so of briskly-paced but uninspiring A-to-B police-work - sticking broadly within the TV show’s remit, albeit with a somewhat harder edge and more attractive locations - help them answer this question to a certain extent, as they uncover the bare bones of an elaborate conspiracy to smuggle heroin into the city, using pre-loaded ‘oriental’ souvenirs carried through customs by unsuspecting tourists.

There are some fun moments during this opening slog - both Anderson and Mayer do solid work, there is some exquisite San Francisco location shooting and I particularly enjoyed the bit where the police’s ‘lab man’ opens up a suspect package with a flick-knife, licks a big dollop of powder off his finger and declares, “yep, it’s heroin alright” - but it is only once the focus shifts elsewhere that the movie really begins.

Indeed, Siegel had literally wanted the film to begin here, as we board a flight into the city and meet the two contractors hired by an unseen cartel to reclaim the hidden dope from its unwitting carriers -- and boy, what a pair they are.

The uncertain relationship between psycho triggerman Dancer (Eli Wallach - blank stare, twisted grimace, porkpie hat) and his older, somewhat effeminate ‘handler’ Julian (brilliantly played by Robert Keith - beady eyes, skull-like grin, pencil moustache) was reportedly intended by Silliphant to mimic that of an aspiring Hollywood star and his agent (“if he continues to listen to me, he’ll be the best,” Julian declares at one point, in the process of talking up his boy’s unparalleled talents in the field of crime). A sly, in-jokey conceit, this approach which works superbly, creating an unforgettably amoral, inscrutable odd couple whose interplay pretty much dominates the film from this moment onward. (2)Once Julian and Dancer (god, that name) are on the scene, Guthrie and Quine fall almost entirely into the background, turning up merely to shake their heads over the latest corpses and radio in for roadblocks and ambulances. We’re 100% with the bad guys on this one, and that’s just as well, because we just can’t keep our eyes off these two creeps - They’re just fascinatingly perverse in every respect.

As Sergio Angelini thus observes in his essay on the film for the Indicator label’s Columbia Noir Vol. 1 box set, “chaos is given a face and a psychological profile while order is merely represented by men in hats”. In truth though, what keeps us so glued to the travails of these goons is that Silliphant and Siegel never allow us to get an angle on - as the guy who gives Dancer the low-down at the port puts it - “what makes [them] tick”. They are nightmare figures from a world we will never understand.

Where did they come from? (The script tells us Miami, implausibly citing their alleged tans, but if so they must have been living underground like moles.) How did they meet? Has Julian spent his entire life recruiting young psychopaths and sponging off their ill-gotten gains like some kind of sociopathic boxing promoter? What exactly is the nature of their relationship? (Let’s not even go there.)

Throughout the film, the characters Dancer and Julian encounter seem as unsure what to make us them as we are. Pushed by their port-side contact, Dancer makes some blunt statement about not having had a father, but that doesn’t really take us very far in terms of armchair psychology. Later in the film, when tearful hostage Dorothy Bradshaw (Mary LaRoche) demands to know “what kind of men” the pair are, the string of gnomic non-sequiturs the lizard-like Julian spits out in response (“women have no place in society”, “crying is aggressive and so is the law”, “people of your class don’t understand the criminal’s need for violence”) raise more questions than they answer.All we know at the outset however is that, like all good agents, Julian has his boy learning proper English grammar (“how many characters on a street corner know how to say, ‘if I were you?’”), tempering Dancer’s sullen, animalistic incomprehension with his own twisted sense of refinement. Meanwhile, he gleefully obsesses over the poetic implications of the last words of the Dancer’s victims, which - in another wonderfully tweisted detail of Silliphant’s script - he scrupulously records in a notebook.

Add a young Richard Jaeckel to the equation as the duo’s feckless ‘wheelman’ - fish-faced, bowtied and alcoholic, he’s been drafted in at short notice after the phony taxi driver we saw in the opening got snuffed - and it’s clear the deck is stacked for some pretty hair-raising mayhem over the next sixty minutes or so.

As Angelini further notes, our ostensible ‘heroes’, the quotidian cops, don’t even get to share any screen-time with these outlandish villains. Mirroring the movie’s opening, Guthrie and Quine only make it to the final showdown in time to despairingly survey the carnage. Seemingly left speechless before the final fanfare crashes in, they are denied even their obligatory “well that just about wraps things up” sign off, closing the movie on a note of nihilistic self-destruction which an empty dedication to hard working SFPD does little to dissipate.

In spite of his legendary status amongst crime/noir aficionados, in truth I’ve always felt that Don Siegel’s work as a director can be a bit hit and miss (it’s difficult to imagine his cult gaining much traction on the basis of pictures like Private Hell 36, for example). Looking across his wider career however, he always seems to come alive when dealing with tales of morally ambiguous anti-heroes or outright maniacs of one kind or another - so of course it figures that he was absolutely at the top of his game for this one. Basically we’ve got the man who brought us ‘Riot in Cell Block 11’ and ‘Dirty Harry’ firing on all cylinders here, and the results are nothing short of spectacular.

In fact, ‘The Lineup’ feels very much like the Ur-text of all past and future Siegel movies, revelling in the pulp-crime aesthetics of his earlier black & white pictures whilst prefiguring elements of the most memorable films he would go on to make over the next few decades (not only the high voltage action and San Fran location work of ‘Dirty Harry’, but the psychotic criminal protagonists of ‘The Killers’ (1964), the elliptical visual storytelling of ‘Charley Varrick’ (1973), and many more besides, I'm sure).

As Siegel wrangles raw, livewire energy, technical precision and unsettling, off-beat artistry here, it’s easy to understand why a young Michael Reeves made a pilgrimage to the director’s doorstep early in the ‘60s to prostrate himself before the master; as a concise summation of the director’s formal strengths and auteurist tics, ‘The Lineup’ is pretty hard to beat.

As with so many of these ‘50s Columbia flicks, the claustrophobic framing and expressionistic shadows of ‘traditional’ noir style have been thoroughly swept away in ‘The Lineup’ (aside from anything else, the entire movie takes place in daylight). Rather than merely falling back on a kind of bland quasi-realism however, Siegel and his DP Hal Mohr offer an alternative visual sensibility which proves just as compelling as the old-time good stuff.

It has often been said that, in a Siegel movie, the camera is always in the right place, and ‘The Lineup’ consistently bears this out, as he and Mohr make inspired use of the by-now-standard widescreen aspect ratio, framing the film’s locations in such a way as to highlight jagged, horizontal lines bisecting bright, white spaces, creating an anxious collage of portside cranes, highway overpasses, art deco tower blocks and advertising hoardings.

Throughout proceedings, the placid serenity of the San Francisco skyline is cut through with a jittery, urban energy, as examples of every means of mechanised transportation known to man (ships, planes, motorcycles - even a blimp at one point) roar hither and yon behind the action, emphasising the relentless velocity of the movie’s plotting whilst casually pre-empting the starkly modernist take on the crime genre inaugurated by John Boorman’s ‘Point Blank’ a decade later.

All of which of course is merely a high-falutin’ way of leading up to the fact that the extended car chase sequence which forms ‘The Lineup’s finale is totally out of control, incorporating a level of stunt-work, action direction and cranked up, adrenalin rush cutting which feels startlingly ahead of its time, pretty much single-handedly inaugurating the “beat THAT” lineage of attention-grabbing car action which would eventually go on to bring us the successive thrills of ‘Bullitt’, ‘The French Connection’, ‘To Live and Die in L.A.’ and so on.Certainly, I’m not aware of anything else from ‘50s that even comes close to this level of visceral excitement. Even though Siegel falls back on using back projection for most of the interior car shots, it’s at least the best back projection you’ll ever see, with the actors’ reactions and the movement of the ‘foreground’ car perfectly timed to match the hair-raising swerves and near misses of the pre-shot footage, lending it a sense of realism which rarely wavers.

In fact, the sweaty, maniacal claustrophobia of these ‘in-car’ shots - which see the crooks collapse into violent, recriminatory mania as their hostages cower and shriek and the car screeches crazily to avoid on-coming traffic - anticipate yet another trope which would become a staple of hardboiled filmmaking a few decades later, primarily on the other side of the Atlantic, where similar in-car chaos was utilised to great effect in films like Mario Bava’s ‘Rabid Dogs’ (1976) and Pasquale Festa Campanile’s Hitch-Hike (1977), amongst others.

And, when we move outside for the wider exterior shots, well, the stunt-work is just honest-to-god breath-taking, climaxing in a heart-stopping emergency stop / handbrake turn on the edge of an unfinished highway overpass which would have given Jackie Chan the jitters thirty years later. (3)

Once we stop to think about it for a few minutes of course, much of Silliphant’s script for ‘The Lineup’ is outrageously implausible. Right from the outset, the idea that an international criminal cartel would go to the trouble of planting shipments of dope on unsuspecting tourists, only to then hire a pair of highly conspicuous out-of-town psychos to collect the goods, leaving a trail of murder victims and drug traces in their wake, is totally absurd.And, that’s before we even get on to the practicalities of smuggling junk in the handles of ivory tableware, or - my personal favourite - the notion that a reclusive, wheelchair-bound mob boss would undertake a dope pick-up himself, in-person and apparently alone… and in a location which can only be reached by navigating multiple flights of stairs, no less!

But, when a movie’s writing is this consistently inventive and attention-grabbing, when the on-screen action is so fast-moving, so packed with wild beauty and delicious craziness, the viewer is forced to engage a mind-set usually reserved for watching giallo and euro-horror movies and simply ask, who cares?

As James Ellroy points out in his characteristically scabrous contributions to the commentary track for the film recorded alongside noir expert Eddie Muller, when it comes down to it, crime fiction is essentially bullshit. Nothing as sensational or destructive as the events portrayed in this film has ever gone down in the annals of real life crime in America - so as long as you’re making shit up, why not go wild?

As in a Fulci or Argento film, each one of the aforementioned scripting absurdities allows for the creation of cinematic moments - most of them heretofore unmentioned in this review - so audacious and unexpected that only the most joyless, movie-hating pedant would really have cause to complain.

From Vaughn Taylor’s ice-cold turn as ‘The Man’, to the assassination Dancer carries out in the steam bath of ‘The Seaman’s Club’, so loaded with unspoken sexual tension it’s a wonder it didn’t jam the projector, to the horribly suggestive sight of Julian tearing apart the innards of child’s Japanese doll as its owner looks on aghast and uncomprehending - almost every scene in ‘The Lineup’ offers something unforgettable. Like some golden treasury of pulp crime excess, it all serves to build a picture of a precarious, morally bankrupt world in which our bourgeois certainties might explode into bloody violence might explode at any moment.

For a ‘50s studio film, ‘The Lineup’ ultimately presents a remarkably frightening conception of the world, and, anchored by exceptional performances for Wallach and Keith, it remains entirely believable on an emotional level, even as the plotting skirts the fringes of outright insanity, helping cementing its place in the pantheon alongside ‘The Big Combo’, ‘Touch of Evil’ and ‘Kiss Me Deadly’ as one of the very best American crime films of the ‘50s. Hard-boiled cinema at its finest.

-----(1) You’ll recall Emile Meyer for his role as the crooked cop in ‘The Sweet Smell oSuccess’ (1957), or perhaps as the priest in Kubrick’s ‘Paths of Glory’ (also ‘57), or as Rufus Ryker in ‘Shane’ (1953). Once you’ve seen him in anything however, his face’ll stick with you, that’s for sure.

(2) Outside of this film, I mainly know Robert (father of Brian) Keith for his role as the unconventional, sympathetic cop character in another excellent San Francisco noir, ‘Woman on the Run’ (1950), but as a solidly reliable character actor he played smaller roles in a raft of quote-unquote ‘classics’ over the years, including ‘The Wild One’ (’53), ‘Guys and Dolls’ (’55) and ‘Written on the Wind’ (’56).

(3) Legend has it that stuntman Guy Way performed this stunt with his own girlfriend in the back seat of the car, doubling the movie’s female hostage. She needed to be helped out of the vehicle, having entered a state of extreme shock, and Siegel later implied in an interview that the couple’s relationship never recovered.