Suitably intrigued, and noting that I already have several Lymington joints stashed unread on my shelves, I chose to begin my investigation with ‘The Star Witches’, because… well, how could I not? It sounds bloody brilliant.

Well, what can I tell you readers - a sense of morbid fascination saw me through to the final pages, but I’m not much inclined to repeat the experience. First published in the same year as ‘The Green Drift’ (though this U.S. edition dates from 1970), ‘The Star Witches’ is, unquestionably, a terrible book. An amazing one though…? I fear not.

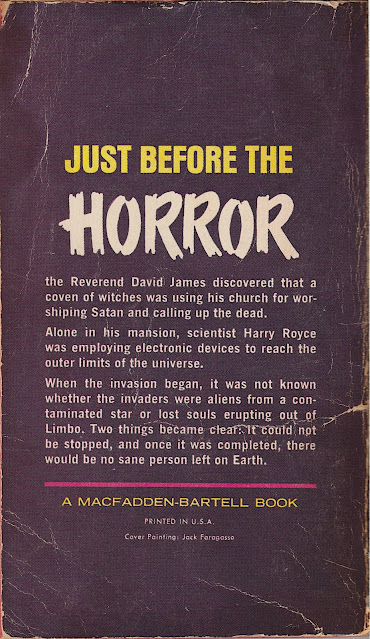

Although nothing in the exciting back cover copy Macfadden’s editorial staff managed to wring out of this damned thing is technically incorrect, the arrangement of these events within Lymington’s text is… not quite as compelling as we might hope, to put it mildly.

The Reverend David James, for instance, only discovers that “..a coven of witches was using his church for worshiping Satan..” via a few throwaway dialogue exchanges towards the end of the novel, and he scarcely has much time to be perturbed by the issue amidst the thunderous rumblings, “cold smells”, petty bickering and great globules of misbegotten, barely coherent, shapeless prose through which Lymington attempts to convey the descent of his (far too numerous) cast of characters into a state of supernatural hysteria as they are buffeted by the assault of some kind of incorporeal alien intelligence.

The Reverend James, by the way, is in no sense the novel’s hero or protagonist - instead he is merely one member of an ever-expanding ensemble of pointless and dislikeable individuals Lymington conjures into existence to stretch out his word count, each chiefly defined by their assorted weaknesses and grotesquery. (The Reverend, for instance, is a venal, self-serving type, possessed of prodigious girth, multiple chins, and invariably described as either picking remnants of fish from his teeth or tripping over his impractical ecclesiastical vestments.)

Mirroring both Wilson’s description of ‘The Green Drift’ and the staggeringly uneventful 1967 film adaptation of Lymington’s ‘Night of the Big Heat’, the “action” of ‘The Star Witches’ is largely confined to the interior of one cold, strange, smelly house (the squire’s abode in a fictional Cotswolds village), wherein upward of a dozen characters gradually accumulate and spend the entire first two thirds of the novel fretting about the absence of one Harry Royce, owner of the gaff in question. An amateur scientist, Royce seems to have disappeared, ‘Marie Celeste’-style, mid-way through his dinner, whilst carrying out some vague researches into matter transference and inter-planetary telepathy, or, y’know - something along those lines.

Harry’s dinner, incidentally, was paprika stew, “with the cheese on the steak,” which his housekeeper (a gargantuan, simple-minded West Country stereotype, like all of the book’s working class characters) repeatedly insists he would never have voluntarily left unfinished. And, if you feel it would be beneficial to receive frequent updates on how long this dinner has been left sitting in his study, and what happens to it as it gradually congeals, and to read several discussions on the subject of whether or not it would be a good idea to clear it away, then, friends - John Lymington is the author you’ve been looking for!

A similar dialectic is invoked on a slightly grander scale during the final third of the book, when, after discovering the body of the absent Mr Royce in a trance-like state within a wall cavity, the characters spend most of the remaining pages arguing about whether they should kill him - in order to destroy the ‘bridge’ his consciousness has formed with the evil alien intelligences which are trying to take over everyone’s minds - or alternatively, just, y’know, not kill him, even though they probably should, just due to general milquetoast queasiness and procrastination on the part of the middle class contingent.

Meanwhile, in the grounds of the house, pound-shop Nigel Kneale vibes are soon the order of the day, as reality warps and frays around Royce’s ‘pepper pot’ private observatory, wherein he has trained his high-tech telescope on the distant planet from which the book’s malign, shapeless entities originate. Eventually, the local residents, tiring of both subterranean rumblings ‘spoiling’ the beer at the pub and their assorted husbands and wives failing to return from the indecisive palaver going down at the manor house, do the decent thing and assemble a pitchfork-wielding mob to take care of business.

Spoiler alert: they do not really succeed, and the book ends, hilariously, with a field report composed by one of the extra-terrestrial invaders, who apparently intend to continue sending signed and dated letters to each other and compiling paper records whilst they conquer the globe, despite being shapeless, nameless telepathic beings from a wholly unknown realm of distant space.

John Lymington is credited with having written over 150 books between 1935 and 1989 - not quite matching the output maintained by his fellow British ‘mushroom pulp’ godhead Lionel Fanthorpe during his peak years, but regardless, Lymington also pumps out his prose like a fog of inarticulate, stream-of-consciousness blather, showing little regard for whether the ends of his sentences bear any relationship to their openings. It reads as if he (like Fanthorpe) was simply dictating the novel into a tape recorder, ‘first thought = best thought’ style, as the clock ticked down to his deadline, before sending it straight off to some poor, underpaid typist to be transcribed.

Fanthorpe however was a worldly and charismatic individual, meaning that the random digressions into his day-to-day which inevitably filtered through into his writing often proved interesting or amusing. (I mean, who wouldn’t want to read 200 bad science fiction novels written by this guy?)

The incessant irrelevancies which accumulate within Lymington’s prose by contrast feel mean, narrow-minded and crushingly banal. It’s all suggestive - though I may be projecting unfairly here - of a kind of culturally blinkered, unhappy existence, the experience of which feels more unhealthy than the writhing, inter-dimensional tendrils of the alien mind-stealers the author rather half-heartedly seeks to invoke in ‘The Star Witches’.

In the first chapter here for instance, we learn that ‘bovine’ housekeeper Clara suffers from wind in the mornings, because her husband Bill puts far too much sugar in the mug of tea he brings her at six o’clock, and which she needs to drink quickly because she needs to get up before seven. We learn that lecherous gardener Bert Gaskin (“known throughout Keynes as a big, blundering, blustering, beggaring knowall”) wears ‘yachting shoes’, because his feet “suffer in hot weather” and “linen shoes can be good for that”. We learn that the doorbell in Harry Royce’s residence is “an original installation from 1850,” and that he “likes original installations”. “Sometimes he had them put in even if they weren’t there when he came,” Lymington would have us know.

Perhaps you think I’m being a bit unfair here. I mean, isn’t it through this kind of detail that all authors develop character, and create a sense of place for their stories? Maybe, but after suffering through a few dozen pages of Lymington, I’d defy you make a case for this excruciating drivel adding up to anything except his daily word count.

It certainly succeeds in torpedoing any promise of the kind of cosmic grandeur which the SF and horror genres are conventionally supposed to deliver, that's for sure, but beyond that, Lymington’s hum-drum eccentricities fail to even register as perversely fascinating or unintentionally funny. Carelessly tossed off, and full of minor lapses of logic so painfully mundane it’s barely worth even registering them, instead it’s all just really annoying.

Indeed, the main feelings generated by spending 140 pages enveloped in the sweaty, feeble mess of ‘The Star Witches’ are those of futility, tedium, mild revulsion… and a creeping realisation that, even for us most dedicated excavators of forgotten 20th century popular culture, there are some stones which are perhaps better left unturned.

No comments:

Post a Comment