Showing posts with label Victoriana. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Victoriana. Show all posts

Tuesday, 22 October 2019

October Horrors # 11:

The Creeping Flesh

(Freddie Francis, 1973)

The Creeping Flesh

(Freddie Francis, 1973)

Although I can’t 100% confirm that this is an accurate memory, I seem to recall that, long ago in the distant past, my initial viewing of a VHS copy of ‘The Creeping Flesh’ might well have marked the point at which my interest in old British horror films first surpassed the level of idle, time-killing curiosity, prompting me to think, “my god, these things are amazing – I think I should probably try to watch as many of them as possible”.

Revisiting the film all these years later, it’s easy to see why my response was so favourable – in a profound sense, it really does the business. Whereas contemporary productions such as Amicus’s And Now The Screaming Starts and Don Sharp’s ‘Dark Places’ appeared to show the British gothic horror tradition on its last legs, exhaustedly dragging itself toward its own grave, ‘The Creeping Flesh’ by contrast is an exuberant, imaginative and confidently realised production, seemingly inheriting a sense of joie de vivre (and, it must be said, a few plot details) from Cushing & Lee’s previous assignment, the equally wonderful ‘Horror Express’.

Although this co-production between Tigon and the utilitarian-sounding World Film Services may not have been planned as an epitaph for this particular strain of British cinema, it was certainly amongst the last batch of such titles to enjoy widespread distribution, and in retrospect, it can’t help but feel like an attempt to give the classical approach to the genre the all-guns-blazing send-off it deserved. (1)

Whilst the film makes a point of evoking as many of the tropes that had helped define the legacy of the preceding fifteen years as possible though, imbuing proceedings with a warm feeling of tried-and-tested familiarity in the process, it also engages intelligently with the more psychological / visceral approach which was already beginning to twist the genre into weird new shapes as budgets plummeted and declining audiences began to demand harder-edged exploitation content (perhaps taking a few notes from Hammer’s envelope-pushing ‘Hands of the Ripper’ (’71) and ‘Demons of the Mind’ (’72)) – a cake-having / cake-eating combo, which, against all the odds, works brilliantly.

An introductory framing narrative features an infirm and unhinged looking Peter Cushing in his lab, ranting about the nature of good and evil and the grave responsibility he holds for saving humanity from a plague of darkness, and so on. As he begins relating his sorry tale to a younger doctor who has apparently turned up to assist him, we move into ‘flashback’ mode as the story proper begins with a scenario akin to what might have happened had Cushing’s character from ‘Horror Express’ managed to return home without incident, and with his crated up specimen still intact.

Upon arrival at his isolated country home, Dr Emmanuel Hildern (for such is Cushing’s character name) is immediately reacquainted with his devoted daughter Penelope (Lorna Heilbron), whom he has left alone at the house during his costly and arduous expedition to the wilds of New Guinea. Naturally enough, Penelope declares her wish to catch up with her beloved father over tea and toast, but Dr Hildern has other priorities, immediately retreating to his laboratory to unpack his big crate.

Excitedly filling his assistant (George Benson) in on the results of his trip, Hildern reveals his prize discovery – a gnarly-looking, giant sized skeleton of some ancient, previously unknown species of hominid, whose very existence throws conventional theories of human evolution into disarray!

Consulting his surprisingly extensive library of work on “the spiritual beliefs of the New Guinea primitives”, Dr Hildern is subsequently inspired to make some even more earth-shattering claims concerning the veracity of his discovery, including the suggestion that it in fact belongs to an ancient race of “evil giants” who once went to war against the people of the islands – and his speculations become even more far-fetched after an attempt to clean the skeleton reveals that the dead bones are capable of actually regrowing their living flesh when exposed to water.

Soon thereafter, Hildern makes the astounding declaration that the blood samples he has taken from this freshly-grown flesh actually contain the essence of pure evil, determining that he and his assistant must get straight to work preparing a prototype vaccine from it, which I suppose in theory should function to rid mankind of all its negative impulses?! (Whoa, back up there Doc, one thing at a time please...)

Whilst begrudgingly taking a break to partake in that aforementioned familial breakfast meanwhile, Dr Hildern gets stuck into his years’ worth of unanswered correspondence, and swiftly learns that his wife, who had been committed to an asylum many years previously, has passed away during his absence. Significantly, it transpires that he had lied to Penelope about her mother’s fate, telling her that she had died whilst she was still a child – so now of course, he must stick to his story and hide his grief from his daughter.

Even more awkwardly for Dr Hildern, the proprietor of his friendly local asylum is none other than his half-brother James, played by Christopher Lee (I suppose the “half” has been appended to the script to account for their obvious lack of family resemblance). Another scientist of questionable propriety, this younger Dr Hildern is soon revealed to be an ice-cold authoritarian who manages his mental hospital with an approach to patient well-being seemingly inspired by Torquemada, whilst spending his spare time engaging in his own Frankensteinian experiments (you know, hand-crank generated electrical charges applied to severed arms in tanks of formaldehyde – all that kind of good stuff).

Clearly there is no love lost between the brothers. Apparently suffering from a severe case of sibling rivalry, James lords his superior wealth and public standing over the grief-stricken and destitute Emmanuel, announcing straight off the bat that he will refuse to subsidise any of his brother’s foolish expeditions, and furthermore declaring that he intends to go head-to-head against Emmanuel to win the much-coveted Richter Prize!

As you’d rather imagine, Emmanuel’s frantic and rather sloppy attempts to knock up a vaccine against Original Sin, Penelope’s calamitous discovery of the truth about her mother (it turns out she was a former Parisian night club performer who allegedly succumbed to a form of hereditary insanity!) and James’s attempts at scientific espionage add up to a whole heap of trouble for all concerned -- especially when you factor in an escaped lunatic rampaging around the place and a big, gnarly skeleton which threatens to turn into an atavistic remnant of a lost race of pre-human destroyers as soon as it’s left out in the rain.

And, as life in the Hildern house becomes ever more dysfunctional, the older Dr Hildern’s extremely bad decision to test out his vaccine on his beloved daughter (I mean, it’s only injecting a solution made from the blood of an ancient evil giant into the blood-stream of an emotionally unstable teenage girl…. what could possibly go wrong?) is basically the last straw that tips the whole thing into complete chaos.

With Cushing and Lee as rival mad scientists, a hot-house gothic house melodrama with overtones of sexual repression and parental abandonment, an ancient, atavistic supernatural menace and a lurid Victorian milieu of hellish asylums, riotous taverns and buxom wenches, ‘The Creeping Flesh’ delivers everything a gothic horror fan could possibly wish for, but, rather than merely coming across as a mega-mix of Brit horror clichés, Peter Spenceley & Jonathan Rumbold’s admirably ambitious screenplay actually succeeds in incorporating all this stuff into an example of that rarest and most valuable of horror movie virtues – a good story, well told.(2)

Critics of the film have tended to draw attention to the unlikelihood of Dr Hildern’s extraordinary leap of logic in determining that he has extracted ‘the essence of pure evil’ from his pet skeleton, and have taken a dim view of the film’s apparent endorsement of the grimly puritanical, Manichean worldview this implies – especially once the injection of the botched ‘evil’ vaccine into Penelope appears to provide the catalyst for her catastrophic sexual awakening. Rarely, it seems, has a horror movie’s “sex = evil = death” message been so explicitly spelled out, and even given scientific credence, no less.

What is easy to overlook on first viewing however is that what we are seeing here is the story as recounted in flashback by Dr Hildern himself – an unreliable narrator to say the least. Whilst the supernatural nature of the creature he has unearthed remains unquestioned, we are never actually given any verifiable proof that the Doctor’s babbling about ancient mythology and good and evil has any basis in fact. Indeed, Spenceley & Rumbold’s script subtly undermines the doctor’s reactionary assumptions at every turn, clearly implying a far more mundane, psychological explanation for the tragedies which plague his family life.

Although Dr Hildern is a genial, sympathetic figure when we first meet him, as the film goes on it becomes increasingly clear that his problems run far deeper than mere bumbling absent-mindedness and nutty-professor style eccentricity. Beyond all of the mad science and monster movie hi-jinks which result from his sloppy professional practice, the clear implication here is that the malady which sends Penelope out on the town in a scarlet dress is the exact same one which drove her mother to the asylum -- and that Emmanuel himself is chiefly responsible for it, irrespective of any botched vaccine injections and vague talk of hereditary insanity.

Through his insistence that his wife and daughter remain closeted from the outside world, and through his failure to understand their needs or to return their affection, Emmanuel has inadvertently destroyed the lives of the two women he loves, and his transition from a lovable bumbler to a tragic, ruined lost soul is, of course, brilliantly realised by Cushing, adding yet another variation to the gallery of morally tormented patriarchs he had previously essayed in films as varied as The Flesh & The Fiends, ‘Cash on Demand’ and The Gorgon. Working here just a few months after his return to active service following the devastating loss of his wife, it is spiriting to see him firing on all cylinders, bringing energy, commitment and emotional nuance to a demanding lead role.

Lee, for his part, falls back on his tried and tested ‘archly superior, cold-hearted cad’ routine, and I’m sure we all know how great he was at doing that. I’m not sure what his characteristically strident thoughts on this particular production may have been, but he certainly seems to be enjoying the opportunity to indulge in a slightly more refined form of full spectrum villainy than his horror roles usually allowed for.

Meanwhile, the supporting cast is excellent too, with Heilbron (who went on of course to work with Jose Larraz on ‘Symptoms’ the following year) on fine, hysterical form as Penelope, and some great one-scene-wonder bits from a few old favourites too; Michael Ripper as one of the porters who carries Cushing’s crate into the house, Harry Locke improvising wildly as the pub landlord, and Duncan Lamont as a drawling Scottish police inspector. There’s even an extended cameo from Jenny Runacre as Cushing’s late wife during some flashback-within-a-flashback scenes of Parisian debauchery.

(The only disappointment in fact is that the hulking, mute asylum escapee is inexplicably NOT played by Milton Reid. Perhaps he was on his holidays at the time? [Cue mental image of Milton relaxing on a sun-lounger drinking a cocktail with an umbrella in it, as Hawaiian music plays.] Oh well, you can’t have everything I suppose.)

Freddie Francis was always rather uneven in his work as a horror director, but he certainly had his moments, and ‘The Creeping Flesh’ is undoubtedly one of them. In particular, he was always a director who seemed to have a good feel for production design, and the staging, props and set dressing here are indeed all top notch. I don’t know where ‘The Creeping Flesh’ actually sat in budgetary terms, but it certainly looks like one of the more extravagantly realised British horrors of its era, with location shooting taking place both around Thorpe House in Surrey and the London Docklands, whilst the standing sets used for the urban exteriors (identified as such by the film’s entry on the Reel Streets website) are so elaborate that I actually mistook them for genuine streets given a period make-over.

Meanwhile, the special effects used to realise the monster – in both its skeletal and fleshy form - are satisfyingly icky and menacing, especially during the film’s climactic nocturnal coach crash – a genuinely thrilling, beautifully evocative sequence featuring great, blue-tinted nocturnal photography, lashing rain, thunder crash editing and a sense of all-consuming chaos as the newly reconstituted revenant makes its getaway in a sutiably menacing hooded cape.

And, as to the ending, well – oh my gosh, it’s so good. The hooded creature banging at the doctor’s door with its clammy paw is just so ‘Weird Tales’, and the vengeful, sanity-wrecking price it eventually exacts from him is so E.C. Comics – just absolute classic stuff (even if Francis does ill-advisedly revive his “camera inside the skull” gimmick from 1965’s ‘The Skull’ to considerably lessened effect).

As you will have gathered, I like ‘The Creeping Flesh’ rather a lot. For some reason, it seems to have remained a fairly under-rated and infrequently discussed entry in the British gothic cycle over the years, but it really is one of the very best, managing to embody all of the arcane joys which this form of filmmaking represents for its fans, whilst at the same time presenting a solid, serious and exciting tale, compelling enough in its own right to make a perfect ‘gateway drug’ for any British horror neophytes who stumble across it. If for some reason you’ve overlooked it until now, please do make the effort to track it down - you’ll be in for a treat.

---

Check out this amazing poster artwork from Italy (title translation: “The Terror From The Rain”(?)), West Germany (“At Night, The Skeleton Awakens”), and Belgium (more or less direct translations of the English title in French and Dutch).

In the UK meanwhile, Tigon put this out on a double-bill with Mario Bava’s ‘A Hatchet For The Honeymoon’ – now THAT’S what I call a good night out!

---

(1)An eclectic production outfit to say the least, World Film Services appear to have had a hand in everything from Peter Watkins’ ‘Privilege’ (1967) and Joseph Losey’s ‘Boom!’ and ‘Secret Ceremony’ (both ’68) to the sub-Amicus portmanteau effort ‘Tales That Witness Madness’ (1973), the inexplicable David Niven vampire comedy ‘Vampira’ (1974), and post-E.T. kid’s sci-fi movie ‘D.A.R.Y.L’ (1985).

(2)Given how accomplished their script for ‘The Creeping Flesh’ is, it is surprising to learn that neither Spenceley nor Rumbold had much of a background in the film industry, and nor did they go on to much recognisable success. Spencely worked intermittently as an assistant editor in the UK, whilst Rumbold next popped up in Greece in 1978, directing a film which no one ever seems to have seen, before occasionally contributing script work to a number of low key productions based out of Greece, Yugoslavia and Iceland.

Labels:

1970s,

asylums,

British culture,

Christopher Lee,

film,

Freddie Francis,

GO,

gothic,

horror,

Lorna Heilbron,

mad scientists,

monsters,

movie reviews,

OH19,

Peter Cushing,

skeletons,

Tigon,

Victoriana

Monday, 30 October 2017

October Horrors #14:

The Flesh & The Fiends

(John Gilling, 1960)

The Flesh & The Fiends

(John Gilling, 1960)

“THIS IS THE STORY OF LOST MEN AND LOST SOULS. IT IS A STORY OF VICE AND MURDER. WE MAKE NO APOLOGIES TO THE DEAD. IT IS ALL TRUE.”

Thus reads the text super-imposed over the picturesque opening shot of 1960’s ‘The Flesh & The Fiends’, an exceptionally seedy grave-robbing melodrama that must surely rank as one of the most artistically accomplished films to have emerged from under the auspices of notoriously tight-fisted British producers (Robert S.) Baker & (Monty) Berman.

Now, before we get stuck into this one, I must confess that the whole Victorian grave-robber/Burke & Hare mythos has never really appealed to me very much. Of all the perennial horror subjects that have persevered through the history of cinema in fact, I’ve always thought that this was one of the least compelling.

In reality of course, the Edinburgh grave-robbing flap in which Burke & Hare played the most infamous part - largely an unfortunate side effect of the city’s medical college allowing impoverished students to pay for their studies in bodies (I mean, what did they THINK was going to happen?) – is fairly interesting, but, in terms of fiction, it doesn’t exactly strike me as a tale that deserves to resound through the ages.

I mean, a few shifty characters start selling bodies to doctors in order to get by - so what? In horror terms, it’s pretty banal stuff. I don’t have much time for real life-inspired serial killer films either, but at least those guys had a certain mystique about them, y’know what I mean?

The best way to approach this subject, I therefore feel, is to bypass the usual logic of a horror film and instead explore the wider milieu of the class inequality and social circumstances underpinning the grim tale… which thankfully is the approach that co-writer/director John Gilling here delivers in spades (no pun intended).

I’ll save you my whole cahiers du cinema bit, but, suffice to say, the deeper I dig into British commercial cinema of the ‘50s and ‘60s (and digging has been slow, but steady over the past decade or so), the more convinced I become that Gilling should be considered as one of the great, lost auteurs labouring in that particular field.

Though the journeyman nature of his career makes it difficult to draw a straight thematic line through all his work, I believe that Gilling’s films tend to be characterised by a strong feel for gutsy, working class directness (not exactly an uncommon trait amongst British directors of his era, admittedly), combined with a black-hearted sense of cynicism aimed at all levels of society – the latter being particularly tangible with regard to the awkward or threatening situations in which different social classes interact.

Such an approach made Gilling a natural for hard-boiled crime movies – indeed, he made numerous films in this vein, and the one I have seen to date (1963’s ‘Panic!’) is excellent – but it also led him into more troubled and uncertain waters when box office trends caused him to turn his attentions increasingly toward horror, science fiction and historical adventures during the ‘60s, lending his work in these genres a raw and morally ambiguous flavour that sometimes proved pretty difficult for audiences to digest.

Front and centre in this regard stands ‘The Flesh & The Fiends’, which, though it is not my personal favourite of his films (hey, dude directed Plague of the Zombies), could well be a contender for Gilling’s masterpiece, should the auteurists eventually come knocking.

From the outset, ‘The Flesh..’ draws a sharp distinction between the austere elegance of the private medical academy presided over by indefatigable anatomical research enthusiast Dr Knox (Peter Cushing), and the raging underworld of unruly taverns and brothels that surround it amid the winding, hilly streets of Edinburgh’s old town - environs from which Burke (George Rose) and Hare (Donald Pleasence) almost literally seem to ooze.

The uneasy flashpoints between these two worlds are highlighted by the characters in the film who come closest to being sympathetic, namely hapless medical student Chris Jackson (John Cairney) and brazen tavern hussy Mary (Billie Whitelaw), whose fumbling, sub-Pygmalion romance eventually leads them both to a miserable end at the hands of messrs B&H, inadvertently exposing the unsavoury conduct of Knox’s preferred corpse-suppliers in the process.

A bleak and furtive exercise in full spectrum cynicism, Gilling’s film venomously attacks the conduct of rich and poor alike, ensuring that even the film’s younger, more ostensibly ‘sympathetic’ characters (to whose ranks we can add a square-jawed ‘good’ medical student and his love interest, Knox’s niece) are variously portrayed as too naïve, vacuous, self-involved, snobbish or undisciplined to even fully understand the games their elders are playing around them, let alone assume any mantle of ‘heroism’.

As Dr Knox, Cushing offers a fascinating variation on the persona he perfected in Hammer’s Frankenstein series, his characterisation of an obsessive, technocratic scientist destroyed by his moral blind spots and lack of human empathy deepened by the more realistic setting offered here.

In a delightful touch, Knox literally turns a blind eye to the crimes of his insalubrious associates, his left eyelid drooping down over a sightless socket – a subtle imperfection that mars his otherwise primly symmetrical appearance, and a brilliant visual metaphor for the fatal character flaw that tips him over the fine line separating a celebrated philanthropic surgeon from a notorious, corpse-mangling monster.

At the other end of the social spectrum meanwhile, Donald Pleasence [in what I believe was his first significant genre role] cuts an equally memorable figure as Willy Hare, portrayed here as a wily tavern parasite and low level thief within whom the discovery of the easy money to be made via late night visits to Knox’s cellar awakens a latent psychopathic tendency, expressed by Pleasence through an increasingly unhinged palette of craven, somewhat effeminate mannerisms that blur the line between melodrama-appropriate scenery chewing and more distrubingly intense, method-ish performance tics.

Pleasance of course comprises one half of a double-act with the largely forgotten actor George Rose, whose idiot-grinning, easily led Burke lends the duo a kind of Satanic, inverted ‘Of Mice and Men’ vibe. After initially being presented as a pair of seedy rogues in the light-hearted Dickensian/Victorian tradition, B&H’s behaviour, and the interplay between them, becomes more uncertain, open-ended and upsetting as the film progresses. As their decision to take up a career as murderers causes the strictly defined parameters of their squalid urban working class existence to begin falling apart around them, their sense of ‘normality’ collapses along with it, causing their actions to become wilder and more unpredictable, with any understanding of cause and effect, let alone right and wrong, completely off the table.

By establishing these characters and their world so credibly, Gilling sets the scene for what is undoubtedly a very effective horror film as well as a social allegory, and the scenes between Burke & Hare and their unfortunate victims are probably the most effective in the picture.

Their first murder in particular is an astonishingly unsettling sequence – probably the most chilling thing I’ve encountered in this whole October review marathon. Certainly, few viewers will forgot the deranged ‘death dance’ that Pleasence performs as he goads his dim-witted companion into suffocating the life out of a derelict old woman, mockingly replicating the scene in real time as she expires before him.

After the deed is done, Hare recoils disgustedly from the sight of a dead rat that the cackling Burke dangles in his face, the queasy balance of power between the duo temporarily upended as their victim, folded in two and shoved in a crate ready for delivery, sits ignored in the corner. It’s as horrifyingly convincing a portrayal of base human villainy as you’re liable to find anywhere within the pulp realm.

Needless to say, with stuff like this going on, ‘The Flesh & The Fiends’ must have proved extremely strong meat for the British film industry in 1960. Perhaps it was the film’s more “serious” historical setting and ostensibly moralistic ending – or perhaps it’s black and white photography and relatively low profile – that allowed it to walk away uncut with an ‘X’ certificate? Who knows. Reading about the troubles Hammer were encountering with the censors at around this time, one imagines Hinds and Carreras would have been flogged in the street and exiled to the colonies if they’d dared to submit a film this packed with whiffy-looking corpses and gruelling on-screen killings for consideration by the BBFC.

This free pass from the censor seems especially curious given that, in stark contrast to the more black & white morality of the travelling theatre-derived Todd Slaughter-style speckle-flecked melodrama from which it draws much of its aesthetic inspiration, ‘The Flesh & The Fiends’ succeeds in asking considerably more complex ethical questions of the viewer than was common in horror films of this era.

Like Richard Fleischer’s ‘10 Rillington Place’ a decade later, Gilling’s film is crystal clear in its argument that, whilst predatory psychopaths and individuals prepared to kill for their own advancement are always with us (and should indeed be held accountable for their crimes), the wider social circumstances of poverty, ignorance and inequality that allow vulnerable people to fall victim to such predation are just as much to blame, if not more so.

In ‘The Flesh..’, these inequalities are personified by the figure of Dr Knox, the wealthy, educated man whose refusal to acknowledge – and willingness to even personally reward - the human suffering that underpins his work makes him the direct enabler of every single act of violence that takes place in the film. A frighteningly prescient metaphor for all of us 21st century first world consumers to ponder perhaps, but one that is problematised by an extremely divisive ending that appears to see the good doctor getting off scott-free. (Again, no pun intended.)

Whilst watching ‘The Flesh &The Fiends’ for the first time, I was absolutely astonished to see Gilling pull a last minute, Scrooge-style moral rebirth on Cushing’s character, exonerating him from blame with a round of applause and even granting him a cloying, moralistic closing speech, effectively allowing the eventual perpetrator of all of the film’s miseries a chance to begin his life anew as a changed man, whilst his lowly-born accomplices swing for the crime literally outside his window.

On first glance, this seems a sickening betrayal of the systematic demolition of hypocrisy within the social hierarchy that Gilling has undertaken across the preceding eighty-five minutes, but, really, the film’s final message all hinges on the way in which each viewer sees the very delicate shading given to the on-screen events falling.

On the surface of it, this is a facile/contrived happy ending that senselessly undermines the message of what has come before; but, if we look past Cushing’s earnest portrayal of a sinner reborn a saint, and the valedictory applause of his sycophantic pupils, we perhaps see a coal-black glint of the director’s true intent shining through.

Because, Gilling seems to dare us to realise for ourselves, this is the way it always goes down in the real world, isn’t it? Time after time, the rich, well-presented man allowed a “second chance”, applauded for his humble recognition of his own “mistakes”, whilst the disreputable lackeys who did his dirty work meanwhile hang dead from the gallows, or succumb to the mob who bay for their blood.

Look around you, skim through today’s paper – it’s happening right now, just as it did in Edinburgh in 1828. Where do you stand, between the jeering of the mob and the empty applause of the students, Gilling seems to be asking us. Because at the end of the day, those are the only choices you’ve got buster, and no square-jawed young hero is going to storm in to change jack shit.

Friday, 29 May 2015

Krimi Casebook:

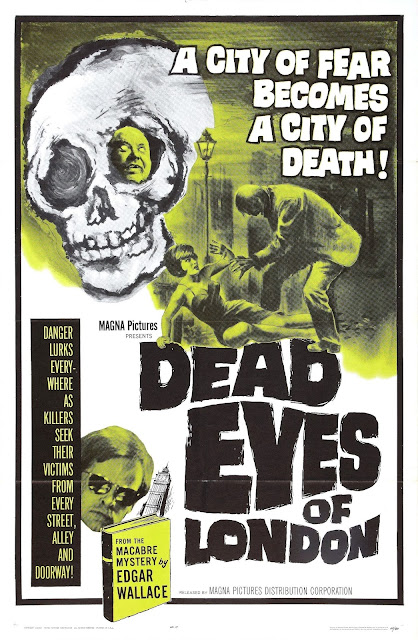

Die Toten Augen von London /

‘The Dead Eyes of London’

(Alfred Vohrer, 1961)

Die Toten Augen von London /

‘The Dead Eyes of London’

(Alfred Vohrer, 1961)

Amid the greasy cobbled streets of a “London” apparently stuck in some strange amalgam of the 1890s, 1920s and 1960s, a visiting Australian wool merchant loses his way in the obligitory peasouper smog. Accosted and beaten by parties unknown, we see him bundled into the back of a sinister white laundry van. “Accidents like this happen every time we have this fog”, remarks the coroner after the corpse is fished out of the Thames the next morning, having to all appearances died a natural death by drowning.

Dashing Inspector Larry Holt of Scotland Yard (Joachim Fuchsberger) is unconvinced by the coroner’s verdict however. “It looks like the blind killers of London are at work again!”, he announces after a torn piece of braille text found in the victim’s pocket is revealed to contain fragments of a threatening message, and the game is afoot in another rousing installment of Rialto Films’ Edgar Wallace ‘Krimi’ series.

Whilst ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ (released in West Germany in March 1961) may not be quite as action-packed as Harald Reinl’s Der Frosch mit der Maske, this first Wallace film by the series’ other key director Alfred Vohrer is nonetheless as an equally impressive achievement. Whilst Reinl’s film cruised by on a sense of pure, pulpy momentum, Reinl’s directorial style is slower and more static, but his trump card here is atmosphere, and, as its title rather demands, ‘The Dead Eyes of London’ (also known as ‘The Dark Eyes of London’) has it in spades.

Apparently owing less to Wallace’s 1924 source novel than to an earlier British movie adaptation from 1939 (with which I’m entirely unfamiliar), ‘Dead Eyes..’ seems, like many Krimis, to fall into that peculiar category of movies that seem to embrace all of the aesthetic trappings of horror film, whilst not actually being horror films.(1)

Certainly, great effort has been taken here to create a feeling of claustrophobic, Jack-the-Ripper-haunted London as rich and indigestible as that of any film ever made in a similar vein. Dark, overhanging streets, canes tapping on cobbled pavements, squalid slums that seem to hide every conceivable variation on grinding poverty and moral degradation, sinister, elongated shadows stretching across each soot-blackened brick wall as misshapen proletarians cringe in fear - you name it, this movie’s got it (well, minus the top hats and horse-drawn coaches at least), all swathed in enough dry ice to put your average Italian gothic moldering in the shade.

Apparently, this particular ‘London’ houses a notorious brethren of blind criminals, who emerge to commit their misdeeds upon foggy nights when, quoth Inspector Larry, “they can more easily take advantage of their victims”. The coldly oppressive atmosphere of the poverty-stricken religious mission from which at least some of these ne’erdowells operate could have come straight from one of Pete Walker’s unsettling ‘70s horrors, and it is within a vast Victorian drainage duct beneath this institution that we find the lair of the film’s chief representative of this loose ensemble of visually-impaired villainy – a hulking, white-eyed ogre named ‘Blind Jack’, as portrayed by an actor (Ady Berber) whom I can only assume was Germany’s equivalent of Tor Johnson or Milton Reid. (Oh, for the days when each national film industry had a gigantic, lumbering brute on call 24/7.)

Although ‘Blind Jack’ provides the closest thing this quasi-horror film has to a monster, handling stalking, stomping, strangling and gurning duties with admirable aplomb, the cynical nature of Krimi plotting of course demands that he and his sightless cohorts are merely pawns in a game beyond their control, as the net of guilt eventually spreads itself far more widely across the film’s more outwardly respectable characters.

It is this side of the story that allows Vohrer to deepen the film’s sense of seedy urban degradation even further, drawing on a well of comic book noir imagery that mix strangely with the quasi-Victoriana of the ‘London’ setting. This feeling hangs particularly heavily over the scenes that take place within the supremely down-market casino / nightclub where many of our gentlemen of ill-repute congregate – a joint where it perpetually seems to be closing time, and the occupants perpetually exhausted; you can almost smell the stale beer and cigar smoke hanging in the air.

It is here, predictably enough, that we’re introduced to the film’s obligatory ‘bad girl’ (Finnish actress Ann Savo), who once again is violently punished for her floozy-ish ways in cheerily misogynistic fashion, assailed by a faceless, black-gloved assassin amid the classic “neon sign outside bedroom window” ambience of her ‘Soho’ bed-sit, in a highly fetishised murder sequence that, whilst not explicitly gory, couldn’t have anticipated the MO of the Italian giallo any more clearly if it had cut to a shot of Mario Bava and Dario Argento crouching outside the window taking notes.(2)

On the side of law and order meanwhile, ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ sees the duo of Fuchsberger and Eddi Arent reunited, but sadly the good feeling that their partnership generated in ‘Fellowship of the Frog’ is rather squandered here. When left to his own devices, Fuchsberger is just fine of course, delivering a mixture of Roger Moore smarm and Stanley Baker-esque determination that makes him the perfect leading man for this kind of movie, but Arent proves more troublesome, having already settled into the persona that he would go on to embody through the majority of his appearances in the Rialto Krimis – namely, that of a comic relief goofball straight from the pits of movie fans’ very own hell.

Whilst ‘Der Frocsh..’ proved that Arent could be a somewhat charming screen presence when gifted with a moderately interesting character to flesh out, here, as Fuchsberger’s perpetually clowning partner, he’s simply a lead weight dragging against the film’s momentum. Veteran comic relief haters in the audience will already feel a shudder down their spines when his character is introduced as ‘Sunny’ (“a nickname that reflects his disposition”), and it’s all downhill from there I’m afraid, as Eddi does his level best to reinforce every unfair stereotype you might have heard about the German sense of humour.

Altogether more pleasing – if equally predictable - is the appearance of a young Klaus Kinski, here essaying the first of a multitude of highly suspicious characters he brought to life whilst on Rialto’s payroll. This time around, Klaus plays a neurotic secretary at a crooked life insurance company, and is just as much of a fidgety, tormented wreck as you might anticipate, sporting gleaming mirror shades in most of his scenes and – dur dur dur! – a pair of black leather driving gloves that his character likes to take on and off all day long, despite exhibiting no particular inclination toward driving.

Naturally, I will refrain from spoiling things by revealing the precise extent to which Kinski’s character is guilty or not guilty of the film’s assorted outrages, but needless to say, I think an aphorism much in the spirit of Chekhov’s gun could well be proposed, stating that if your murder mystery movie features Klaus Kinski skulking around in a pair of Ray-Bans, you probably won’t be needing that ID parade when it comes to fingering the killer, however elaborate his “obvious red herring” alibi may seem.

Inevitably, ‘The Dead Eyes of London’ features it’s fair share of procedural drag in between these assorted highlights, but, as in all the best entries in this series, touches of visual imagination and black humour often are used to liven up duller moments, as exemplified early in the film when a potentially tedious and exposition-heavy visit to the aforementioned life insurance company is livened up by a flick-knife welding blackmailer and some amusing business with a skull-shaped cigarette holder.

Also keeping things interesting meanwhile is an intermittently hair-raising score, as provided by the supremely named Heinz Funk. Though used only sparingly, Herr Funk’s compositions offer a mixture of beat-inflected suspense jazz and dissonant, primitive electronics that sounds somewhat like the result of John Barry and Pierre Boulez getting their demo reels mixed up in one of “London”s dark alleyways.

As a director, Vohrer’s camera tends to remain fairly static, but he does seem to display a love for odd stylistic twists that tend to make his compositions stand out, including a few fun process shots utilising complex arrangements of mirrors and reflections. In what is perhaps the film’s most bizarre moment, Vohrer utilises a truly odd “inside of mouth” shot, complete with giant cardboard teeth in the foreground, to dramatise the entirely unimportant detail of an old geezer spraying his gob with breath freshener prior to leaving the bathroom.

The time and effort taken to create such a weird shot, with no apparent narrative justification, seems entirely inexplicable within the normal working methods of low budget commercial cinema, but its presence does perhaps go some way toward demonstrating the kind of freedom that Rialto’s directors were allowed in this period – a freedom that possibly helps explain why the best of the Krimis stand out as so much more fun and inventive than most of their competitors in the early ‘60s Euro b-movie stakes.

And, insofar as I am qualified to pass judgment at this relatively early stage in my immersion in the genre, ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ would indeed appear to be a truly exemplary example of Krimi style – a creaky, meandering potboiler enlivened, and indeed even twisted into entirely new shapes, by an admirable combination of cinematic craftsmanship, grisly gallows humour and a rogue’s gallery of strikingly memorable character players; the result being an exquisitely sinister time-waster, enriched with enough weird visual fibre to make it a keeper over half a century after everyone should have stopped caring.

----------------------------------------------

(1) Other black & white era examples of the not-quite-horror-film that immediately spring to mind include ‘Tower of London’ (1939), Vincent Price’s break-out picture ‘Dragonwyck’ (1946) and the truly peculiar Charles Laughton vehicle ‘The Strange Door’ (1951), amongst many others.

(2) Whilst it is foolish of course to try to assign any direct chains of influence when dealing with vague and general notions such of these, the this scene in ‘Dead Eyes of London’ could be seen as anticipating Bava’s pivotal ‘Blood & Black Lace’ (1964) on several levels - not only via the aestheticised sadism of the murder and the anonymous, black gloved killer, but even the strobing effect provided by the flickering neon sign outside the window seems a precursor to that film’s antique shop sequence. (If you want to stretch the point even further, could even make the case that a memorable death-by-lift-shaft sequence elsewhere in the film could have provided the inspiration for the conclusion of Argento’s somewhat Krimi-informed ‘Cat O’ Nine Tails’ (1972) as well.)

Monday, 15 July 2013

Pelican Time:

The Victorian Underworld

by Kellow Chesney

(1970)

(Gustave Doré)

(Illustrated London News, 1852)

(George Cruickshank)

(‘Preparing for an execution at Newgate, 1848’. Mansell Collection.)

(‘A Spree in a Railway Carriage’, about 1850. Mansell Collection.)

(Gustave Doré)

(From ‘The Day’s Doings’, about 1870. Mansell Collection.)

A comprehensive and no doubt endless fascinating & astounding volume, which I am very much looking forward to reading properly when time allows. All illustrations are contemporary to the period, credited as above.

Labels:

1970s,

books,

history,

London,

non-fiction,

Pelican,

Victoriana

Monday, 2 August 2010

The Great God Pan and The Inmost Light by Arthur Machen

(John Lane editions, 1894)

(John Lane editions, 1894)

“Look about you, Clarke. You see the mountain, and hill following after hill, as wave on wave, you see the woods and orchards, the fields of ripe corn, and the meadows reaching to the reed beds by the river. You see me standing here beside you, and hear my voice; but I tell you that all these things - yes, from that star that has just shone out in the sky to the solid ground beneath our feet - I say that all these are but dreams and shadows: the shadows that hide the real world from our eyes. There is a real world, but it is beyond this glamour and this vision, beyond these ‘chases in Arras, dreams in a career,’ beyond them all as beyond a veil. I do not know whether any human being has ever lifted that veil; but I do know, Clarke, that you and I shall see it lifted this very night from before another’s eyes. You may think all this strange nonsense; it may be strange, but it is true, and the ancients knew what lifting the veil means. They called it seeing the god Pan.”

Clarke shivered; the white mist gathering over the river was chilly.

“It is wonderful indeed,” he said. “We are standing on the brink of a strange world, Raymond, if what you say is true. I suppose the knife is absolutely necessary?”

-----

Although unburdened for the most part by conventional literary merit, the fifty pages of Arthur Machen’s ‘The Great God Pan’ somehow remain unique, and indeed shocking, reading, over a century after they were composed.

Now clearly I don’t ACTUALLY own an original edition of ‘The Great God Pan’ with Aubrey Beardsley cover illustration, but the great Welsh mystic writer has been on my mind a lot this week, so it seems a good opportunity to post some covers to his work that are more worth looking at than the volumes I do own.

Firstly, I was thinking on Machen because I’ve been reading S.T. Joshi’s The Weird Tale, which begins with an essay on his work. A nice drive through the rolling hills of Brecon and Herefordshire on the way to hunt books in Hay On Wye brought him to mind again, and upon arriving, I actually managed to grab a copy of a Joshi-edited Machen collection, incorporating both ‘The Great God Pan’ and his much sought after (by me, at least) weird novel ‘The Three Imposters’.

This collection (The Three Imposters and Other Stories) is published by the fiction wing of Call of Cthulhu role-playing game magnates Chaosium, a circumstance which initially seems bizarre given how little of Machen’s wider work has even the vaguest connection to Lovecraftian horror. One overnight re-read of ‘The Great God Pan’ later however, and the fact that Machen’s legacy is largely kept alive by Weird Tales freaks, despite his authorship of endless, rambling stories in which nobody does anything more exciting than go for a nice walk, suddenly makes perfect sense.

Aside from anything else, the vast influence the story must have held over H.P. Lovecraft as he created his Cthulhu Mythos tales is self-evident. Machen’s fragmentary structure, full of aimless digressions, portions of letters and detailed descriptions of drawings and architecture, his flat, utilitarian characters, his ‘nameless horrors’ that immediately drive men to madness and suicide, and above all, his endless dark hinting, hinting, hinting, bursting occasionally into orgiastic stretches of purple prose – all of these devices will be intimately familiar to Lovecraft fans, however baffling and poorly realised they must seem to outsiders.

Beyond that though, ‘The Great God Pan’ provides a perfect example of my frequently spouted notion that the best literary horror stories are always those that spring from unsound minds. For, moreso even than Poe or Lovecraft, Arthur Machen was, shall we say… a complicated man.

I first read ‘The Great God Pan’ in the Dover edition where it is printed alongside his later work ‘The Hill of Dreams’(1907), a thinly veiled autobiographical novel which, perhaps uniquely for a weird tales author, manages to be even more strange and upsetting than his horror stories, as he speaks in naive and almost self-delusionary terms of his deep loneliness and confusion with life, of his obsessive hatred of modernity, of his endless faith in finding transformative spiritual ecstasy within the landscape around him, and, most worryingly, of what modern readers can only interpret as his ‘punishment’ of his errant sex drive through frequent self-flagellation.

All of these themes can of course also be found bubbling away under the surface of Lovecraft’s writing, but the difference is that for Machen, the metaphysical ideas he made central to ‘The Great God Pan’ were actually very dear to him. Whereas Lovecraft’s cosmic horrors – though still incredible – were gradually formalised in his later stories into a kind of grand, archaic science fiction, Machen’s conception of the material world as merely a ‘veil’ that could be lifted from the eyes of man revealing the shining face of the ‘true’ universe were key to most of his life and work.

What is terrifying about ‘The Great God Pan’ then is the way that it sees Machen’s pure spiritualism perverted (by the author himself, or by the imperfect human beings in the story?) into terms of chaos, insanity, darkness, mad science, deformity and Luciferian evil, with the monstrous sexuality implied by the figure of Pan looming large, if never explicitly referenced.

In fact, it could be said that the enduring power of ‘The Great God Pan’ lies in the fact that VERY LITTLE is explicitly referenced. Beyond the shortcomings of the story’s muddled narrative, Machen’s understanding of the power of suggestion is necessarily masterful, managing to coerce readers into drawing the threads together themselves, providing just enough leathery yarn for us to construct ourselves one ugly lookin’ pentagram, while Machen stands outside, his conscience ‘clean’, reminding us that HE never used any dirty words.

Perhaps Machen was even TOO successful in achieving this effect, as he still saw his tale roundly condemned as decadent garbage upon publication, with a reviewer for the Westminster Gazette memorably dismissing ‘The Great God Pan’ as “an incoherent nightmare of sex”, despite the fact that Machen is at pains not to make so much as a single reference to sexual relations or human physicality in the whole book. (Machen's early work actually attracted so many negative or baffled reviews that years later he published a whole volume of them, under the title “Precious Balms”.)

Nonetheless though, there is a lot more at stake in ‘The Great God Pan’s avoidance of direct explanation than mere Victorian prudishness. The central idea underlying the story is so vast in metaphysical scale, whilst its earthly expression in Machen’s imagination has become so cruel and sickening, that when the author commences his ‘dark hinting at nameless things’ routine, he is genuinely tiptoeing around ideas that he either wouldn’t (for fear of ridicule of his deeply held beliefs), or couldn’t (for fear of censorship and public disgust), state explicitly.

This genuine fear of revealing the story’s ‘truths’ is a rare thing indeed in horror fiction, where writers are more usually assumed to glory in their dark revelations, and Machen’s simultaneous fascination with, and repulsion toward, his own subject matter, itself the result of his obsession with atavistic mysticism crashing headfirst into his deeply buried sexual repression, makes ‘The Great God Pan’ stand out, for all its technical faults, as one of the foremost Cosmic Horror stories of all time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)