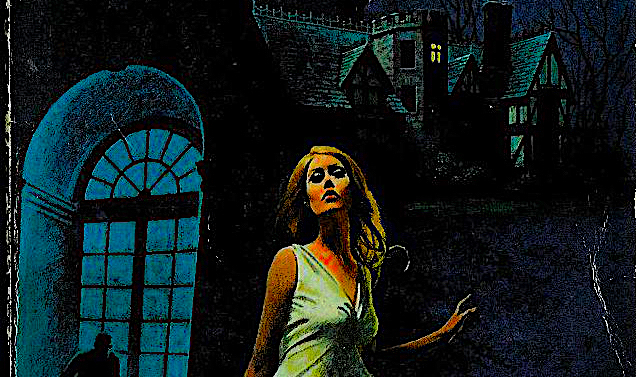

One of the more frequently overlooked entries in Italy’s cycle of ‘60s gothic horrors, ‘La Cripta e L’incubo’ had escaped my attention prior to its re-emergence this year as part of Severin’s

Eurocrypt of Christopher Lee box set. It is all the more satisfying therefore to discover that it actually holds up as one of the very best second-tier Italio-gothics, muscling in just below the canonical classics of Bava, Freda and Margheriti in my own personal ranking of such things.

Leaving aside for a moment the contributions of director Camillo Mastrocinque (who went on to helm the similarly underappreciated Barbara Steele vehicle An Angel for Satan two years later), ‘Cripta e L’incubo’ seems to have been a project chiefly instigated by its co-writers, future director Tonino Valerii and the ubiquitous Ernesto Gastaldi.

As Valerii and Gastaldi have both recalled in interviews, their script for the film was produced in a single, heavily caffeinated all-night writing session, after producer Mario Mariani called their bluff by telling them he’d finance the top flight horror picture Gastaldi was boasting about having written, if they could drop the script round to his office the following morning.

The fevered, ‘first thought / best thought’ approach to writing which resulted from this circumstance is perhaps reflected in the pleasantly disjointed mish-mash of ideas which eventually made it to the screen.

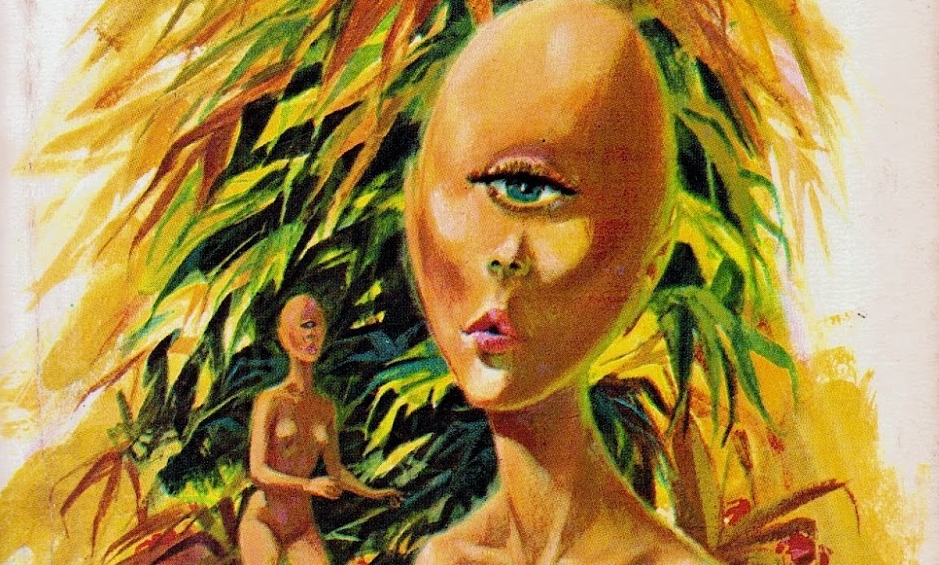

Expanding upon a garbled retelling of Le Fanu’s ‘Carmilla’ (already filmed by Roger Vadim as the epochal ‘Blood & Roses’ a few years earlier), the two writers add a largely unconnected opening half hour cribbed either from Hammer’s ‘Dracula’ or Corman’s House of Usher (bequiffed young hero José Campos has arrived at the sinister castle to catalogue and restore the library of Christopher Lee’s saturnine Count Karnstein), alongside assorted hints of Gastaldi’s future notoriety as an architect of the giallo (see below), some blatant borrowings from Bava’s ‘Black Sunday’/‘La Maschera del Demonio’, and a startling injection of below stairs black magickal intrigue which anticipates the kind of imagery more commonly encountered in the wave of Erotic Castle Movies which kept the Euro-gothic tradition alive through the ‘70s.

Charged with knitting all this together into a coherent whole, Mastrocinque - a veteran director tackling his first horror film here after decades of comedies and melodramas - seems to have faced a certain amount of criticism over the years, not least from Valerii and Gastaldi, neither of whom seem to have held him in high regard. Reading between the lines, one suspects the younger writers may have resented not being given the opportunity to take a crack at directing their script themselves, whilst the fact that Mastrocinque sacked Gastaldi’s wife (the recently departed Mara Maryl, R.I.P.) from the film after less than a day on set can scarcely have helped matters.

The director has also been criticised though by some later commentators, who have accused him of failing the lacking a ‘feel’ for the horror genre - an accusation I find rather unfair.

Admittedly, both of Mastrocinque’s horror films are lugubriously paced even by the standards of this sub-genre, downplaying the kind of visceral shocks modern viewers might expect, and ‘Cripta e L’incubo’s early scenes do feel rather stiff and uninvolving, but regardless - once the film gets going, it is positively dripping with the very best kind of gothic atmos, as the director’s rather stately, old fashioned style intersects quite beautifully with the more irrational, exploitational content the writers have jammed into the screenplay.

Right from the outset, the use of one of Italio-gothic’s homes-from-home, the Castello Piccolomini in Balsorano, as the primary shooting location adds greatly to the sense of crumbling, atavistic weirdness (the Castello’s later tenants included both Lady Frankenstein and The Crimson Executioner), whilst a frantic, wild-eyed performance from Adriana Ambesi as the troubled Laura Karnstein also immediately grabs our attention. Though she still looks appropriately stunning in her period accoutrements, Ambesi brings a distraught, human fragility to her character which sets her apart from the icy brunettes who usually dominate this emotionally frigid sub-genre.

Carlo Savina’s score meanwhile nails down the mood perfectly with dissonant, droning organ chords, creepy harp arpeggios and gratuitous theremin, and from the moment we hear a ghostly church bell tolling across the desolate valley housing the deserted ruins of the village which once bore the Karnstein name (subsequently seen in evocative location shots of some suitably blighted/abandoned locale), we know we’re getting the real deal here.

Presumably by accident rather than design (although he was certainly old enough to remember them the first time around), Mastrocinque draws here on imagery recalling the pre-war ur-texts of Euro-horror, giving us diaphanous, slo-mo curtains dancing in the breeze (ala Epstein’s 1928 ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’) and Cocteau-esque pools of translucent darkness, along with glass-topped coffins, spectral, ruin-dwelling crones, and other faint echoes of Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931).

At the same time though, ‘Cripta e L’incubo’ also pre-empts much of the more envelope-pushing content which would come to dominate the genre as time went on, giving the film a bit of a transitional feeling - a gateway from one mode/era of horror filmmaking to another, if you will.

As noted above, Valerii & Gastaldi have got the basics of the ‘Carmilla’ story rather muddled here, so that their Karnstein family are actually the occupants of the home into which the Carmilla surrogate character (renamed Ljuba, and played by Ursula Davis) is welcomed following the traditional coach crash.

In this retelling furthermore, the daughter to which the predatory vampire turns her attentions (that of course being Laura) already has a whole heap of trouble on her plate, what with being hypnotised into participating in black magick rites at the behest of housekeeper/covert witch Rowena (Nela Conjui), causing her to experience occasional possession by the spirit of her inevitable, curse-declaiming witch ancestor (whom we see in flashback meeting her grisly fate at the hands of the Inquisition, in a blatant lift from ‘Black Sunday’). In addition to to this, Laura also suffers from nightmares in which she experiences real-time visions of crimes perpetrated by Ljuba prior to her arrival at the castle. Poor lass - no wonder she’s feeling a bit flustered.

The lesbian connotations of the ‘Carmilla’ story may be subtlety handled here, but - presumably following the example of Vadim’s film - they are still present, which must have been dynamite for audiences in ’64. Meanwhile, red-blooded cinemagoers were also given the opportunity to thrill to the sight of Ambesi’s naked back, which is presented to us on multiple occasions, not least in particularly kinky context during the Satanic rites and the inquisition sequence (I don’t really need to tell you that Ambesi plays her own ancestor during the flashbacks do I?) The highly suggestive nightmare sequence in which Laura’s assorted female tormenters appear at her bedside bearing over-sized goblets of blood (paging Dr Freud), is also excellent.

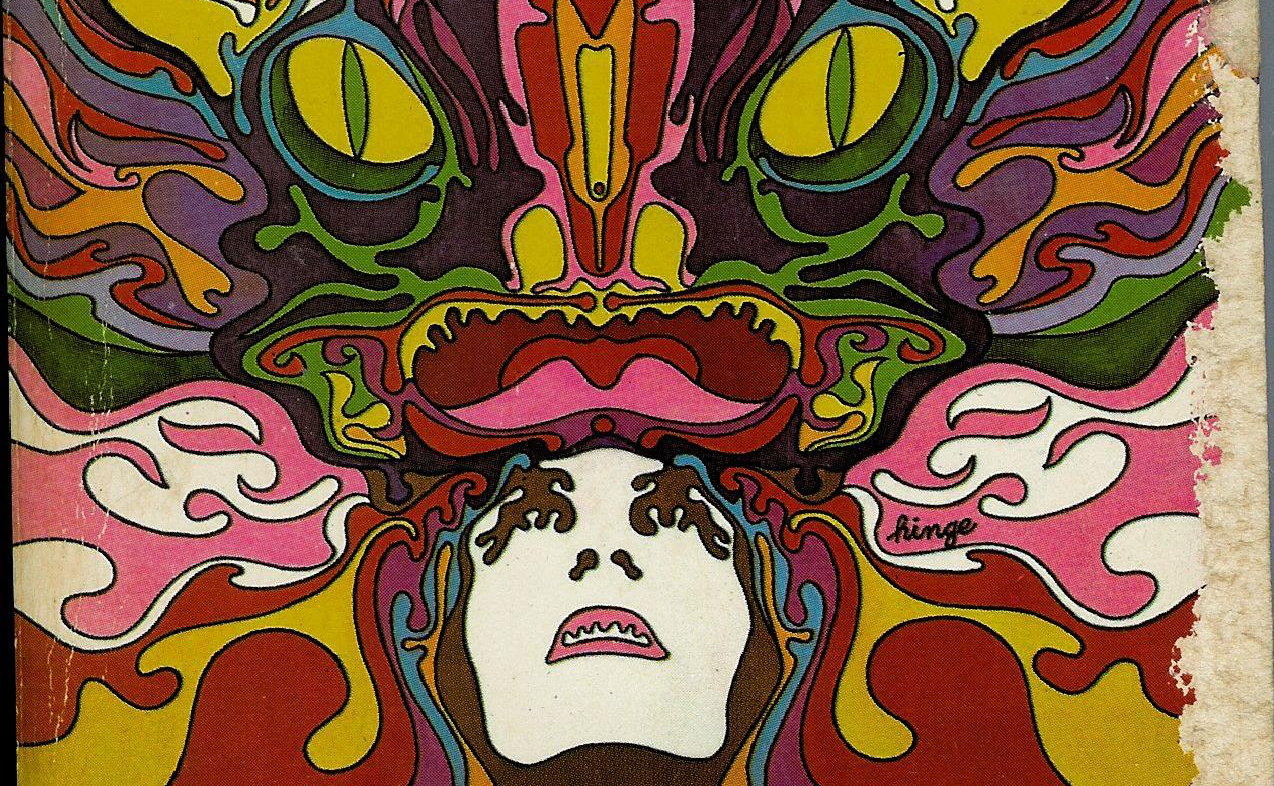

Speaking of which, all that occult stuff down in the catacombs - sans any real explanation of its origins or narrative purpose - feels incredibly potent and deranged. Bearing a paper pentangle covertly sliced from an ancient manuscript, the malevolent Rowena calls upon the spirit of her infernal mistress, as a mesmerised Laura drops her robe and lays face down, spread eagled within the crudely wrought magic circle, and Savina’s music explodes into a cacophony of fevered gong battering and shrieking, ring-modulated feedback. Again, wild stuff for the early ‘60s.

The comingling of vampirism and diabolism may be old as the hills (even creeping into Hammer’s ‘Brides of Dracula’ and ‘Kiss of the Vampire’ in the years preceding this), but it still elicits a charge of pure weirdness which I never tire of, whilst the trope of a domestic servant turning to black magick to commune with his/her departed mistress/master is one which would recur incessantly through the next few decades of Euro-horror.

In particular, Rowena’s practice has a DIY / folkloric aspect to it which I find interesting. Late in the film, she whips out a ‘hand of glory’ (nearly a decade prior to ‘The Wicker Man’), and the sequence in which she creeps through the castle’s nocturnal halls, bearing her strange talisman, is one of the most evocative and wordlessly weird in the movie, providing a great showcase for the classically crepuscular monochrome cinematography (provided either by Julio Ortas or Giuseppe Aquari, depending on whop you speak to).

I’ve long believed there is a thesis waiting to be written on the symbolic significance of hands in Italian gothic horror (seriously, they’re everywhere), and the presence of this crudely embalmed murderer’s extremity, traditionally left burning at a victim’s bedside, could no doubt provide some great ammunition to the brave scholar tackling such a topic.

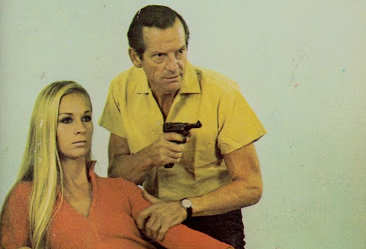

For a more direct expression of sexuality meanwhile, look no further than the scenes between Lee (looking rather louche in a terrific quilted dressing gown, monogrammed with an appropriately gothic ‘K’) and Véra Valmont, playing housemaid Annette. Rather surprisingly in view of the usual bottoned up conventions of the sub-genre, we at one point see the pair lounging about together in the Count’s bed chamber, having completed the latest bout in what appears to be a long term affair.

Surprisingly mature and cynical, the couple’s dialogue in this scene transcends the pulpy/melodramatic writing usually encountered in gothic horror, giving us a rather more interesting and ambiguous character relationship, which, as mentioned above, anticipates the kind of thing Gastaldi in particular would make his bread and butter in later years, once the giallo kicked off as a viable genre later in the decade.

All of this aided greatly by Mastrocinique’s decision - repeated in ‘An Angel For Satan’ - to play things totally straight, refusing to wink to the audiences or leave room for sniggers, even as the narrative piles up genre clichés like dirty dishes; mismatched remnants of delicious, pulp/comic book indulgence.

By maintaining a stately pace and liminal, laid-back tone, the director gives his cast the opportunity to stretch out and deliver something closer to ‘proper’ performances than was common within the genre. Lee (who provides his own voice on the English dub) seems more relaxed than usual here - grateful perhaps to be playing a low key, relatively sympathetic, role instead of being slathered in ‘walking dead’ face paint as per many of his other European Counts - whilst Ambessi, Valmont and Conjui are all very good.

Above all, ‘La Cripta e L’Incubo’ is a mood piece, and as such, it is probably not for all tastes. Those liable to be frustrated by the film’s sedate progress through a disjointed, weirdly structured and cliché-ridden narrative may prefer to give it a wide berth. But, for those of us who love the texture, the atmosphere, and the underlying sense of oneiric delirium which define Italian gothic horror, it is an absolute treat - a pure draught straight from the well of the genre’s fetid, short-lived high water mark.

---