Friday, 29 May 2015

Krimi Casebook:

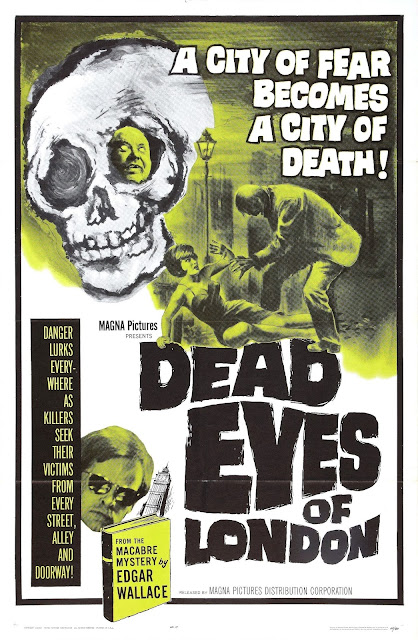

Die Toten Augen von London /

‘The Dead Eyes of London’

(Alfred Vohrer, 1961)

Amid the greasy cobbled streets of a “London” apparently stuck in some strange amalgam of the 1890s, 1920s and 1960s, a visiting Australian wool merchant loses his way in the obligitory peasouper smog. Accosted and beaten by parties unknown, we see him bundled into the back of a sinister white laundry van. “Accidents like this happen every time we have this fog”, remarks the coroner after the corpse is fished out of the Thames the next morning, having to all appearances died a natural death by drowning.

Dashing Inspector Larry Holt of Scotland Yard (Joachim Fuchsberger) is unconvinced by the coroner’s verdict however. “It looks like the blind killers of London are at work again!”, he announces after a torn piece of braille text found in the victim’s pocket is revealed to contain fragments of a threatening message, and the game is afoot in another rousing installment of Rialto Films’ Edgar Wallace ‘Krimi’ series.

Whilst ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ (released in West Germany in March 1961) may not be quite as action-packed as Harald Reinl’s Der Frosch mit der Maske, this first Wallace film by the series’ other key director Alfred Vohrer is nonetheless as an equally impressive achievement. Whilst Reinl’s film cruised by on a sense of pure, pulpy momentum, Reinl’s directorial style is slower and more static, but his trump card here is atmosphere, and, as its title rather demands, ‘The Dead Eyes of London’ (also known as ‘The Dark Eyes of London’) has it in spades.

Apparently owing less to Wallace’s 1924 source novel than to an earlier British movie adaptation from 1939 (with which I’m entirely unfamiliar), ‘Dead Eyes..’ seems, like many Krimis, to fall into that peculiar category of movies that seem to embrace all of the aesthetic trappings of horror film, whilst not actually being horror films.(1)

Certainly, great effort has been taken here to create a feeling of claustrophobic, Jack-the-Ripper-haunted London as rich and indigestible as that of any film ever made in a similar vein. Dark, overhanging streets, canes tapping on cobbled pavements, squalid slums that seem to hide every conceivable variation on grinding poverty and moral degradation, sinister, elongated shadows stretching across each soot-blackened brick wall as misshapen proletarians cringe in fear - you name it, this movie’s got it (well, minus the top hats and horse-drawn coaches at least), all swathed in enough dry ice to put your average Italian gothic moldering in the shade.

Apparently, this particular ‘London’ houses a notorious brethren of blind criminals, who emerge to commit their misdeeds upon foggy nights when, quoth Inspector Larry, “they can more easily take advantage of their victims”. The coldly oppressive atmosphere of the poverty-stricken religious mission from which at least some of these ne’erdowells operate could have come straight from one of Pete Walker’s unsettling ‘70s horrors, and it is within a vast Victorian drainage duct beneath this institution that we find the lair of the film’s chief representative of this loose ensemble of visually-impaired villainy – a hulking, white-eyed ogre named ‘Blind Jack’, as portrayed by an actor (Ady Berber) whom I can only assume was Germany’s equivalent of Tor Johnson or Milton Reid. (Oh, for the days when each national film industry had a gigantic, lumbering brute on call 24/7.)

Although ‘Blind Jack’ provides the closest thing this quasi-horror film has to a monster, handling stalking, stomping, strangling and gurning duties with admirable aplomb, the cynical nature of Krimi plotting of course demands that he and his sightless cohorts are merely pawns in a game beyond their control, as the net of guilt eventually spreads itself far more widely across the film’s more outwardly respectable characters.

It is this side of the story that allows Vohrer to deepen the film’s sense of seedy urban degradation even further, drawing on a well of comic book noir imagery that mix strangely with the quasi-Victoriana of the ‘London’ setting. This feeling hangs particularly heavily over the scenes that take place within the supremely down-market casino / nightclub where many of our gentlemen of ill-repute congregate – a joint where it perpetually seems to be closing time, and the occupants perpetually exhausted; you can almost smell the stale beer and cigar smoke hanging in the air.

It is here, predictably enough, that we’re introduced to the film’s obligatory ‘bad girl’ (Finnish actress Ann Savo), who once again is violently punished for her floozy-ish ways in cheerily misogynistic fashion, assailed by a faceless, black-gloved assassin amid the classic “neon sign outside bedroom window” ambience of her ‘Soho’ bed-sit, in a highly fetishised murder sequence that, whilst not explicitly gory, couldn’t have anticipated the MO of the Italian giallo any more clearly if it had cut to a shot of Mario Bava and Dario Argento crouching outside the window taking notes.(2)

On the side of law and order meanwhile, ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ sees the duo of Fuchsberger and Eddi Arent reunited, but sadly the good feeling that their partnership generated in ‘Fellowship of the Frog’ is rather squandered here. When left to his own devices, Fuchsberger is just fine of course, delivering a mixture of Roger Moore smarm and Stanley Baker-esque determination that makes him the perfect leading man for this kind of movie, but Arent proves more troublesome, having already settled into the persona that he would go on to embody through the majority of his appearances in the Rialto Krimis – namely, that of a comic relief goofball straight from the pits of movie fans’ very own hell.

Whilst ‘Der Frocsh..’ proved that Arent could be a somewhat charming screen presence when gifted with a moderately interesting character to flesh out, here, as Fuchsberger’s perpetually clowning partner, he’s simply a lead weight dragging against the film’s momentum. Veteran comic relief haters in the audience will already feel a shudder down their spines when his character is introduced as ‘Sunny’ (“a nickname that reflects his disposition”), and it’s all downhill from there I’m afraid, as Eddi does his level best to reinforce every unfair stereotype you might have heard about the German sense of humour.

Altogether more pleasing – if equally predictable - is the appearance of a young Klaus Kinski, here essaying the first of a multitude of highly suspicious characters he brought to life whilst on Rialto’s payroll. This time around, Klaus plays a neurotic secretary at a crooked life insurance company, and is just as much of a fidgety, tormented wreck as you might anticipate, sporting gleaming mirror shades in most of his scenes and – dur dur dur! – a pair of black leather driving gloves that his character likes to take on and off all day long, despite exhibiting no particular inclination toward driving.

Naturally, I will refrain from spoiling things by revealing the precise extent to which Kinski’s character is guilty or not guilty of the film’s assorted outrages, but needless to say, I think an aphorism much in the spirit of Chekhov’s gun could well be proposed, stating that if your murder mystery movie features Klaus Kinski skulking around in a pair of Ray-Bans, you probably won’t be needing that ID parade when it comes to fingering the killer, however elaborate his “obvious red herring” alibi may seem.

Inevitably, ‘The Dead Eyes of London’ features it’s fair share of procedural drag in between these assorted highlights, but, as in all the best entries in this series, touches of visual imagination and black humour often are used to liven up duller moments, as exemplified early in the film when a potentially tedious and exposition-heavy visit to the aforementioned life insurance company is livened up by a flick-knife welding blackmailer and some amusing business with a skull-shaped cigarette holder.

Also keeping things interesting meanwhile is an intermittently hair-raising score, as provided by the supremely named Heinz Funk. Though used only sparingly, Herr Funk’s compositions offer a mixture of beat-inflected suspense jazz and dissonant, primitive electronics that sounds somewhat like the result of John Barry and Pierre Boulez getting their demo reels mixed up in one of “London”s dark alleyways.

As a director, Vohrer’s camera tends to remain fairly static, but he does seem to display a love for odd stylistic twists that tend to make his compositions stand out, including a few fun process shots utilising complex arrangements of mirrors and reflections. In what is perhaps the film’s most bizarre moment, Vohrer utilises a truly odd “inside of mouth” shot, complete with giant cardboard teeth in the foreground, to dramatise the entirely unimportant detail of an old geezer spraying his gob with breath freshener prior to leaving the bathroom.

The time and effort taken to create such a weird shot, with no apparent narrative justification, seems entirely inexplicable within the normal working methods of low budget commercial cinema, but its presence does perhaps go some way toward demonstrating the kind of freedom that Rialto’s directors were allowed in this period – a freedom that possibly helps explain why the best of the Krimis stand out as so much more fun and inventive than most of their competitors in the early ‘60s Euro b-movie stakes.

And, insofar as I am qualified to pass judgment at this relatively early stage in my immersion in the genre, ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ would indeed appear to be a truly exemplary example of Krimi style – a creaky, meandering potboiler enlivened, and indeed even twisted into entirely new shapes, by an admirable combination of cinematic craftsmanship, grisly gallows humour and a rogue’s gallery of strikingly memorable character players; the result being an exquisitely sinister time-waster, enriched with enough weird visual fibre to make it a keeper over half a century after everyone should have stopped caring.

----------------------------------------------

(1) Other black & white era examples of the not-quite-horror-film that immediately spring to mind include ‘Tower of London’ (1939), Vincent Price’s break-out picture ‘Dragonwyck’ (1946) and the truly peculiar Charles Laughton vehicle ‘The Strange Door’ (1951), amongst many others.

(2) Whilst it is foolish of course to try to assign any direct chains of influence when dealing with vague and general notions such of these, the this scene in ‘Dead Eyes of London’ could be seen as anticipating Bava’s pivotal ‘Blood & Black Lace’ (1964) on several levels - not only via the aestheticised sadism of the murder and the anonymous, black gloved killer, but even the strobing effect provided by the flickering neon sign outside the window seems a precursor to that film’s antique shop sequence. (If you want to stretch the point even further, could even make the case that a memorable death-by-lift-shaft sequence elsewhere in the film could have provided the inspiration for the conclusion of Argento’s somewhat Krimi-informed ‘Cat O’ Nine Tails’ (1972) as well.)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Most krimis didn't make it to US theaters. This one did and did well. It's probably the most well remembered krimi in the States, thanks to the scary look of the hulking Ady. Bela Lugosi was in the original film called The Human Monster as well as Dark Eyes of London/Dead Eyes of London.

Post a Comment