Watching Kim Ki-Young’s 1978 film ‘Woman After A Killer Butterfly’* for the first time is likely to be a fairly strange experience for any viewer. But for those of us watching it ‘blind’, as it were – with no prior knowledge of the director’s work, or of his place within Korean cinema – it’s gonna be a real a real doozy. An 8.5 on the weirdo richter scale, call-the-WTF-police, high level freakiness jamboree. You know the deal, I’m sure.

You also know, presumably, that nine times out of ten when the shadier end of international horror/fantasy cinema throws up what appears to audiences in the English-speaking world to be an A grade piece of mind-blowing bafflement, such impressions can be primarily attributed to cultural differences, general ignorance on our part and a failure to appreciate the limitations and conventions within which these marginal filmmakers were working. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, I hasten to add – it’s just the way things are, all part of the fun as we stumble our way through uncharted cinematic territory.

What is far more interesting however is that one time out of ten when things get strange in a way that is genuinely unaccountable, and what we’ve got here is a case in point. Because rather than the unhinged, culture clash style weirdness one tends to associate with Asian movies, ‘Killer Butterfly’ is an intelligent, self-aware, extremely well made and internationally informed film that just happens to be… completely inexplicable.

My reason for bringing all this up is simply that what with the film (and several other of Kim Ki-Young’s key works) suddenly being available to view on Youtube courtesy of the Korean Film Archive, it seems likely that ‘Killer Butterfly’ will sooner or later be turning up alongside ‘Mystics in Bali’ and ‘Housu’ on somebody’s list of ‘Top Ten Crazy-Ass Loony Asian Horror Films That You Gotta See’ or somesuch - an inclusion that even the slimmest amount of research (and that’s all I’ve done, needless to say) would reveal as both undeserved and deeply inappropriate.

First off, ‘Killer Butterfly’ isn’t really a horror film. With its wealth of grotesque gothic imagery and supernatural happenings, it could easily be mistaken for one, but no... it's true intentions lie somewhere else entirely. At a push, you could maybe claim it as a ‘fantasy’ film, but again, none of the elements we’d associate with such a tag are really catered for. Although Kim Ki-Young certainly delights in playing with genre elements, at the end of the day ‘UNCLASSIFIABLE’ is the only drawer you’re really gonna be able to file a film like this in. But more on that later.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, Kim Ki-Young’s background and career is about as far removed from that of yr average regional lo-fi horror maniac as it’s possible to get.

Spending time in Japan after WWII, he became a devotee of American and European cinema, and gained his first experience of film-making producing newsreels for the US army during the Korean War, after which he was in on the ground-floor of South Korea’s own national cinema, shooting his first features (including the country’s first film with synchronised sound) on equipment he’d requisitioned from the Americans. Working solidly through the late ‘50s on neo-realist style films and social melodramas, he could very much claim to be one of the founding fathers of his country’s film industry, and proceeded to follow the path of an independent minded auteur/arthouse filmmaker as closely as circumstances allowed. Critical plaudits and relative financial success in South Korea ensued, and it was only after his international ‘breakthrough’ film – 1960’s ‘The Housemaid’ – that controversy began enter the picture.

Apparently, ‘The Housemaid’s outbursts of expressionism and Bunuel-esque subversive turmoil marked a shocking departure from the strain of optimistic realism that had until then predominated in Korean cinema, and, following the film’s success, the director pushed further toward what is described as his ‘mature style’ during the ‘60s – a style that his reassuringly informative Wikipedia page describes as being characterised by “..gothic excess, surrealism, horror, perversions and sexuality”. Our kinda guy, in other words!

When the Korean film industry (along with most other national film industries) hit the ropes during the ‘70s, Kim began to produce his films independently, with the financial assistance of his wife (a successful dentist) allowing him more freedom than ever before to indulge his eccentric tastes, resulting in a series of ambitious films that, despite a sizeable cult following and a surprising level of box office success, seem to have been met with what I can only assume was a sense of bafflement and indignation from the rest of the Korean film industry – at least if the near complete absence of this venerable and prolific director from the country’s annual ‘Blue Dragon’ and ‘PaekSang’ awards ceremonies, and the corresponding low profile of his films overseas, is anything to go by.

Returning to ‘Killer Butterfly’ with this background in mind, it all begins to make a bit more… well, not sense exactly, but its existence becomes more understandable, let’s put it that way.

As Todd of Die, Danger, Die, Die, Kill! observed when he reviewed the film a few months back, the only way to successfully convey the alien logic of ;Killer Butterfly' is via straight plot description. Normally I’d prefer to avoid such synopsis-heavy reviewing, but sometimes (as with Alabama’s Ghost, for example) I’m afraid it’s the only way to go. So, if you’re sitting comfortably, let’s begin.

Young-gul (Kim Chung-chul) is a nervous young medical student, who is enjoying a day out in the countryside pursuing his favourite hobby, catching butterflies. As he spikes one of his specimens with a syringe, a well-dressed woman approaches him and begins haranguing him for his cruel treatment of the creatures. “When it comes to death, people are no different, it’s just as trivial” she argues, rejecting Young-gul’s assertion that the death of a human is “much more noble” than that of an insect. The two apparently agree to disagree, and the woman offers Young-gul a cup of juice, which he accepts. Only when it is too late does she reveal that the juice is in fact poisoned, explaining that she had come to this remote place to die, but didn’t want to enter the afterlife alone.

Freaking out as he collapses into a coma, Young-gul subsequently awakes in hospital, where a rather slack police inspector informs him that the woman did indeed die, throws him her butterfly pendant as a memento, and lets him go free. Arriving home (he seems to live in a squalid mountainside shack, somewhat reminiscent of the one where all that crazy shit goes down in the second ‘Female Prisoner: Scorpion’ film), Young-gul finds himself plunged into a deep depression by the incident, and, feeling there is a now “poison in his soul”, decides to kill himself.

Young-gul’s suicide is interrupted however by an elderly travelling bookseller, who repeatedly barges his way into the shack, proffering copies of a book extolling the virtue of ‘strength of will’, a creed which the man insists can inspire one to immortality. Enraged by this cackling weirdo upsetting his solemn date with death, Young-gul eventually stabs the man with a kitchen knife, but, mortally wounded, he continues to jabber on, even as his blood drains away and his heart stops beating. Tiring of the now undead man’s continuous diatribe and the smell of his decomposing body, Young-gul sets out to bury him, and, when he returns from his shallow grave still preaching the virtues of willpower, to burn him. Following his cremation, the old man returns yet again as a walking, talking skeleton, who beats Young-gul with his bony arms, laughing at him and mocking his desire to die. A gust of wind enters the shack and reduces the skeleton to ash, but the old man’s disembodied voice raves on, proclaiming that his spirit will live on forever, as his essence drifts off on the winds.

Apparently impressed enough to take the old man’s advice for the moment, Young-gul puts his suicide on hold and returns to college, where a buddy of his convinces him to help out with a unique money-making scheme. Visiting a complex of caves, they break off from the guided tour and sneak out with the bones of an ancient skeleton, that Young-gul’s friend has arranged to sell to Dr. Lee, a prominent archaeologist, for a healthy profit. Left alone to assemble to skeleton in his shack, Young-gul is… well I was going to say astounded, but actually he seems to take it in his stride… when the skeleton regrows its flesh, assuming the shape of a beautiful, pale-skinned woman, who explains that she had fled into the caves 2,000 years ago, using Shamanic magic to keep her spirit in limbo until ‘the right man’ – that presumably being Young-gul – stumbled across her bones and resurrected her.

Unfortunately, if Young-gul’s ancient bride is to retain her corporeal form, the Shaman’s spell decrees that she must eat a raw human liver within ten days, or else return to a sack of inanimate bones. Refusing to hunt down a liver for her, Young-gul tells her she’ll have to find one herself, leaving her complaining of her unquenchable hunger as she eyes up the liver of her prospective husband…

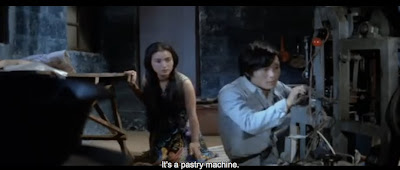

How will this unsettling drama play out? Well we won’t find out quite yet, because some men have arrived at the shack, carrying a large piece of industrial machinery. “What’s that?”, the 2000 year old woman asks. “It’s a pastry machine!”, Young-Gul replies. “I thought we could use it to make some money on the side”.

Aaand, that’s where we’re going to have to leave our extended plot synopsis for the moment. So far, I’ve only covered about the opening forty minutes of ‘Killer Butterfly’s two hour run time, but… the pastry machine. It’s too much. You’ll just have to watch it for yourself and find out.

Actually, in a certain sense, this kind of high weirdness, that makes the film so noteworthy for jerks like me, kind of works against its overall artistic success in some ways. I mean, in essence, ‘Killer Butterfly’ is sort of a classical tragedy that tries to tackle weighty cosmic issues of life and death and rebirth etc. But after watching it, all I could think was, jesus christ… the pastry machine.

Anyway, after this apex of grand strangeness is over and done with, the film finally breaks away from the random, episodic anti-narrative that has prevailed thus far, and settles down (in a manner of speaking) into merely an intense gothic melodrama with a sub-plot about a secret society who dress up as butterflies to desecrate graves and send severed heads to a renowned archaeologist (or something).

In brief, Young-gul shrugs off the 2,000 year old woman caper, and takes up a job as assistant to the aforementioned Dr. Lee, moving into his richly appointed home and becoming involved with his equally death and butterfly obsessed daughter Kyungmi (Kim Ja-ok), with the pair’s chaste and tempestuous non-relationship proceeding to dominate the remainder of the film.

Whilst the preceding scenes have been characterised by an unmistakable strain of knockabout black humour, from hereon in things become more tricky to interpret, as the film strikes an uneven balance between metaphysical earnestness and grotesque genre parody that often becomes quite offputting.

Is Kim Ki-Young genuinely trying to make some grand, Jodorowsky-style Point about life and death, being and nothingness here? The intensity with which he treats these scenes in which characters yammer on and on about the solace of death and when and why they intend to put an end to their bleak existence, and the commitment of Ka-ok and Chung-chul’s startling performances as the doomed un-couple, certainly suggests as much, recalling the uncompromising emo-turmoil of heavy hitters like Zulawski’s ‘The Devil’ (1973) and Sion Sono’s ‘Love Exposure’ (2008).

But at the same time, this stuff is just ploughed through over and over, raised to such an absurdly heightened pitch of melodramatic silliness, it simply CANNOT be taken seriously, often verging onto some epic pastiche of the brand of melodrama that holds a central place in Korean film & TV. As noted, Kim Ja-ok’s performance is astonishing, but her character’s hand-wringing, self-obsessed Young Werther style angst soon becomes absolutely interminable, as does Young-gul’s impotent terror of the world around him, and Dr. Lee’s laughably overblown macho dedication to his daughter. And meanwhile, the whole far more interesting (to me at least) business of the butterfly-masked graverobbing cult remains sadly unexplored.

There IS undoubtedly a strong element of absurdist comedy running through the film - in contrast to the later reels, the whole 2000 year old woman section is both hilarious and strangely touching, and the film’s ‘horror’ bits have a great Evil Dead/Sammo Hung slapstick feel to them. But as things get more overwrought, the script’s uneasy blend of parody and pathos makes it very difficult to really get an angle on where Kim Ki-Young is coming from with all this stuff, emotionally speaking.

Where he’s coming from visually speaking is at least a lot clearer, as ‘Killer Butterfly’ gleefully draws on recognisible horror imagery throughout, with skulls and skeletons and candelabras and gothic hoo-hah infesting just about every frame, as the film rambles back and forth across the boundaries of life and death. It’s difficult to ascertain whether or not the influence of European horror is deliberate, but as fans of such things will no doubt have already noticed from the screengrabs accompanying this review, ‘Killer Butterfly’s dense, hyper-real colour scheme certainly has a lot in common with the more imaginative gialli, and the brooding fantasias and unnatural light sources of Mario Bava’s early/mid ‘60s work in particular.

Very much unlike a horror film however is ‘Killer Butterfly’s unhurried, leisurely pace, as the film strays freely from any kind of narrative tension with the freedom that becomes a filmmaker unchained from commercial necessity, as wholly tangential scenes – a beach party, a visit to the hospital – are transformed by Kim Ki-Young into outlandish tone poems of sumptuous colour and texture that are a joy to behold, even when the action on-screen becomes repetitive or incomprehensible. In fact, as the film progresses, this uniquely expressive approach to cinematography (which doesn’t exactly make for easy viewing on youtube, it must be said) seems to reflect the story’s obsessive concern with the battle between life and death, as bright patches of vivid, burning colour are consumed amid an ocean of impenetrable, inky blackness – an idea that is arguably conveyed far more powerfully through the visuals than it is through much of the script.

A horribly glib comparison perhaps, but after looking over Kim Ki-Young’s CV and watching a few of his films, I can’t help but think that discovering his work is a bit like stumbling across the Korean David Lynch. Clearly both are hugely talented and ambitious filmmakers who can command a strong popular following (Kim was apparently awarded the nick-name ‘Mr. Monster’ by his fans) and could easily sit at the forefront of their respective national industries, were it not for their insistence on producing films that many critics deem maddeningly eccentric and excessive – bulbous, overbearing, upsetting and impossible works, but never less than wholly original, with a strong streak of untamed genius always running wild.

With this in mind, perhaps the best way for us Westerners to explain the singularity of something like ‘Killer Butterfly’ is to say that watching it is a bit like taking someone who’s largely ignorant of American cinema and beginning their education by showing them ‘Lost Highway’ or ‘Mulholland Drive’ – an overwhelming and disorienting experience to say the least, but, given the chance, who amongst us wouldn’t want to dive straight in and savour the madness?

*Some sources go for the simpler English title of ‘Killer Butterfly’, whilst the film’s own subtitles identify it as ‘Chasing the Butterfly of Death’, and English text on the Korean poster states ‘Woman With Butterfly Tattoo’. So make of that what you will.

No comments:

Post a Comment