Friday, 28 September 2012

Deathblog:

Herbert Lom

(1917-2012)

Herbert Lom

(1917-2012)

Sad to hear yesterday of the death of one of another one of those great “dude was in EVERYTHING” type actors, whose face fans of ‘60s and ‘70s movies have probably spent longer looking at than they have their own parents, the one and only Herbert Lom.

Funnily enough, I think Lom was perhaps the first non-household name character actor I ever learned to recognise and pay attention to, via his memorably unhinged performances in the Pink Panther films, which, like just about everything else in said movies, amused and interested me a great deal as an 11 year old. Since then his distinctive visage has popped up somewhere or other in just about every stage of my filmic education, and last Christmas, whilst idly watching the second half of “El Cid” on TV, my brother and I were amazed to realise that we could immediately recognise him solely via his eyebrows, in a role that requires him to spend most of the movie wearing a turban and facemask.

Closer to the stamping ground of this blog, it seems Lom never quite gets his due as a horror/genre star (perhaps because he pursued a successful mainstream career in parallel?), but just cast your mind back over some of the weird & wonderful stuff the guy was in over the years: Hammer’s underrated “Phantom of the Opera”, Jess Franco’s “Count Dracula” (bringing a surprising dose of gravitas to the role of Van Helsing, I seem to recall), “Mark of the Devil”, not mention being turned into a miniature killer toy robot Lom in one of the premier ‘WTF am I watching here!?’ moments in all British horror, in Amicus’s “Asylum”. Before that, he was in a bunch of great British noir/b-movies like “Hell Drivers” and “The Frightened City”, and hey, we haven’t even mentioned “The Lady Killers” yet. Then there’s Ray Harryhausen adventure movie “Mysterious Island” (1961), Massimo Dallamano’s unbelievable “Dorian Gray” (1970), Michele Soavi’s “The Sect”, Cronenberg’s “The Dead Zone”, spy movies like “Assignment to Kill” and “Our Man in Marrakesh”, Franco’s first WIP movie “99 Women”, and…. well, you get the idea. Dude was everywhere, and the sight of his eyebrows looming into shot is always a welcome one. R.I.P.

(Photo borrowed from If Charlie Parker Was a Gunslinger..)

Wednesday, 26 September 2012

FRANCO FILES:

Dracula: Prisoner of Frankenstein

(1972)

Dracula: Prisoner of Frankenstein

(1972)

Context:

Of these, ‘The Erotic Rites of Frankenstein’ is usually held to be the most noteworthy – in fact it’s one of the wildest pictures Franco ever made - but I think ‘Dracula: Prisoner of Frankenstein’ also has its charms. A slightly more low key effort, its general vibe has a lot in common with the kind of tired, last gasp gothic horrors that independent producers in Europe still seemed to be making in defiance of all reason in the early ‘70s (think ‘Lady Frankenstein’, ‘Frankenstein’s Castle of Freaks’, that sort of thing). But, Franco being Franco, he puts a uniquely strange and somnambulant spin on the material, resulting in a movie that is… certainly unlike anything else being offered up by the commercial film industry in 1972.

Content:

Largely plotless and featuring no real dialogue in the opening half hour (and precious little after that), ‘Prisoner of Frankenstein’ exists within that magic moment when the production of genre-based exploitation footage becomes so mindless and automatic that the results emerge as almost entirely abstract, bordering on avant garde. Kind of a zen-like ‘first thought / best thought’ meditation on the proliferation of horror movie imagery through popular culture, perhaps? Or alternatively, just imagine if some joker kept spiking Al Adamson’s coffee with ketamine and you’ll be thinking along the right lines.

In fairness, some kind of a storyline does begin to develop in the second half of the film, communicated largely via a post-production voiceover from Dennis Price’s Dr. Frankenstein. Although his conventional monster seems to be doing quite well for itself, the Baron seems to have an altogether more ambitious scheme in mind this time around. Announcing that he “now rules the great beyond”, Frankenstein has succeeded in attaining dominion over the spirit of Count Dracula (Howard Vernon) and another female vampire (Britt Nichols), intending them to head up a “new and bizarre army, an army of shadows” that he claims will allow “the great beyond” to “overpower the world”. So there ya go. Any questions?

Kink:

Creepitude:

Bats both real (stock footage?) and laughably unreal (flopping about on strings, perhaps left over from 1970’s ‘Count Dracula’?) are much in evidence, and Howard Vernon seems to be popping up outside windows and doors all over town, white-faced, top-hatted and baring his fangs like some sort of Dracula/Orlof crossover, as intermittent bursts of lightning strike, and prolific Spanish actress Paca Gabaldón freaks out in what I think was her only role for Franco, rocking back and forth humming to herself and shrieking in a room full of by neo-primitive sunflower paintings and straw dollies… (an example of the common Franco motif of occasionally cutting to seemingly unconnected scenes of an unidentified woman experiencing some sort of mental breakdown, perhaps implying that she’s either dreaming the action on screen, or else a prior victim of its antagonists, cf: ‘Lorna the Exorcist’, ‘Nightmares Come At Night’).

Grumpy looking Alberto Dalbes rides around endlessly in a coach, whipping his horses and looking determined, whilst Dennis Price favours a vintage motor car, in which he cruises around (sometimes with Vernon sharing the back seat) looking thoroughly suspicious in a fur-collared coat and fez. Back at the chateau, he’s got a superb collection of mad scientist gear on the go (lots of flashing lights!), and his own monster to play with (an endearingly dirt-cheap, rubber mask approximation of the Karlof monster, it’s a more traditional creation than ‘Erotic Rites..’ rather bizarre “bodybuilder painted silver” effort).

Probably the film’s strangest scene is the one in which Price resurrects Dracula by draining the blood of the kidnapped cabaret singer into a bell-jar containing a bat (a real one, alarmingly - seeing the poor blighter floundering around as they dribble ‘blood’ all over it is pretty uncomfortable), as lights flicker and the mad scientist machines whir away like happy hour at the Radiophonic Workshop. At the crucial moment, the doc hits the power switch, a fizzing coil overheats, and bat, bell-jar and everything suddenly disappears in a puff of smoke, leaving a fully sized, opera-caped Howard Vernon lying there! Top dollar horror flick craziness.

Soundtrack-wise, Bruno Nicolai’s score from ‘Justine’ is re-used wholesale here, but his bombastic, James Bernard-esque theme actually sounds a lot more comfortable and less irritating in this pulpy, ghoulish context. Elsewhere, a strange backdrop of exaggerated wind sounds, looped animal cries and disembodied melodic humming proves incredibly atmospheric, summoning that eerie, earthy atmosphere that characterises many of the best ‘70s Spanish horror films. 4/5

Pulp Thrills:

Altered States:

With almost every shot climaxing in some kind of weird, meandering zoom, zeroing in on some seemingly random detail, this is precisely the kind of slap-dash, zoom-heavy direction that Franco’s detractors have always ridiculed, but once you get used to the technique, it has its own idiosyncratic appeal. Breakin’ all the rules just for the sake of speed and laziness, it allows the film to run free alongside the director’s wavering attention, as his unpredictable camera movements imitate the way one’s eyes might shift back and forth across an unfamiliar scene. It may be the complete opposite of the well-planned, deliberate filmmaking that we’re all taught to respect and aspire to, but here we actually get to witness in real-time the process of the director noticing something or other, thinking “whoa, check that out”, and filling the screen with it, just because he feels like it. The effect is disorientating, and the constant disruption of on-screen space can be near intolerable at first, but the more of these films you watch, the more you’ll learn to love the woozy, displaced feeling that results.

The somnambulant pacing too is something that neophytes are just going to have to roll with if they want to remain conscious beyond the halfway point. Regardless of what transpires in them, Franco films are never exactly ‘fast-paced’ (Stephen Thrower has spoken of him filming according to his own “internal, metabolic tempo”, or something like that), and the way he lets scenes drag and wonder and drift into each other has a tendency to make any sense of logic or connection between the images disappear entirely. Once again here, he manages the unique feat of taking a film in which a huge number of things happen, but almost all of them fall out of the viewer’s mind immediately, leaving us with the impression that we’re stuck in a kind of trance-like, repetitive limbo, as the clock slooowly rolls by. In the best possible way, of course. 4/5

Sight-seeing:

Don’t take my word for it though – writing on imdb in November 2000, one ‘Maxorin-2’ commented that:

“This is the horror film with the best castle I've ever seen. It's better than all that castles of the Hammer. Trust me. It's bigger and darker. Very strange and interesting. I've visited it in Alicante, Spain, and it seemed to me that Dracula was walking around. If you want to be scared go on and watch it.”

Duly noted. 4/5

Conclusion:

If you’re unafflicted by the malady, then the film’s complete lack of narrative drive or audience involvement, its lethargic pacing and inept, disorientating zooms, will likely prove insufferable, to the extent that you may find yourself furious that this aimless garbage is actually being offered to you as a piece of structured entertainment. And that’s fine. You’re better off that way. Just walk away, put something else in the DVD player. You’ve got a long and fulfilling life ahead of you.

For those of us who’ve already succumbed to the sickness though, it’s too late - this is pure nectar of the gods. Drink it in in all its pointless, zonked out glory, my brethren, and go to a happy place. I’ve watched it three times at the time of writing, and I’ll likely watch it again. In the Church of Franco, we can ALL rule the great beyond.

Wednesday, 19 September 2012

FRANCO FILES:

Mil Sexos Tiene La Noche

(1984)

Mil Sexos Tiene La Noche

(1984)

AKA:

I don’t think this one was ever released in any English-speaking territories, but if (like whoever sub-titled my copy) we go the direct translation route, then it is my duty to inform you that today we’re going to be talking about a film called ‘Night Has 1,000 Sexes’.

And, much has I’d love to leave you to contemplate such titling decisions at your leisure, I’m afraid it’s also my duty to inform you that, thanks to a brief mix up whilst typing the Spanish title into imdb, I discovered that the notorious Spanish slasher movie ‘Pieces’ was first released in 1983 under the name ‘Mil Gritos Tiene la Noche’ (‘Night Has 1,000 Cries’), leading me to suspect that the producers of this entirely unconnected Franco film simply jumped on that name for a quick buck and a bit of a laugh. (And of course, the ‘Pieces’ title itself seems to owe a certain debt to ‘The Awful Dr. Orlof’s original Spanish title of ‘Gritos en la Noche’, so who knows – maybe Franco was just getting his own back in some obscure fashion.)

Context:

As with most of the films Franco made for ‘Golden Films Internacional’ during the ‘80s, it looks as if this one enjoyed a brief release in Spain before disappearing altogether, with none of the international repackaging that most of his earlier films were subject to. Who were those guys, and was it really in their best interests to pay Franco to make so many movies? Did these things actually play in theatres in Spain? Did anyone go to see them? All questions for us to ponder in the dark hours of the night (1,000 sexes notwithstanding).

Content:

A loose reworking of 1970’s already pretty loose ‘Nightmares Come At Night’, this quintessential Franco fable has Lina Romay playing a psychic living in the Costa Del Sol, where she demonstrates her powers in a (surprisingly non-erotic) cabaret act in collaboration with her husband, played by Daniel Katz (I guess Antonio Mayans must have been having a week off).

Of course it’s only a matter of time before she falls under the spell of a sinister witch – Carmen Carrion in the familiar Lorna/Princess Obongo role – who apparently possesses Lina’s body as she sleeps, sending her out as a kind of succubus to kill her enemies. Strained mental health, reality/fantasy confusion, pot smoking, sapphic groping and tormented naked writhing naturally ensues. Happy days.

Kink:

Less explicit than many of Franco’s ‘80s films, ‘Mil Sexos..’ makes up for it by virtue of being far more stylish, hitting a rare peak of visual imagination and formal experimentation that often harks back to his dreamy ‘70s hey-day.

It would be ungallant of me to dwell on the fact that Lina looks a bit tired out in some of the film’s early scenes (and an absolutely appalling pair of baggy pyjamas doesn’t help), so we’ll skip over that and just say that she certainly regains her customary enthusiasm later on. Katz unfortunately is dead weight, and Carrion’s screen-time is minimal, but if there’s one thing Franco knows when he’s on form, it’s how to make something out of nothing, and some of the hazy, beautifully shot erotic dream sequences he pulls off here could probably have functioned with no human component whatsoever. A super slow-paced lesbian tryst at a pot party is also one of the film’s highlights - a great trance-like scene, with an underlying menace that’s distantly reminiscent of something outta ‘Blue Velvet’ or ‘Twin Peaks’, as Daniel White’s droning, echoplexed freak-out music hits hard, throwing animal cries and death-like moans into the mix for an atmosphere of implied psychic violence. 3/5

Creepitude:

“What’s that you’re reading?”

“An old book: it’s called… Necronomicon.”

H.P. Lovecraft’s sanity-compromising tome makes a welcome return to the Franco-verse, although as usual the bits that we hear read aloud from it sound pretty distant from anything you’d expect to find within the scrawl of the Mad Arab. Naturally the book’s inclusion doesn’t really lead up to anything of particular interest, but although the central psychic domination / subconscious witchcraft motif isn’t explored half as powerfully here as it was in some of Franco’s better takes on this over-familiar subject matter (‘Macumba Sexual’ and the astonishing ‘Lorna the Exorcist’ spring to mind), the film’s unusually captivating technique ensures that things rarely drag, with the atmospheric barometer rarely dipping beneath the level of “thoroughly sinister”.

In fact several moments here are pretty damn spooky, with Franco using sudden focus switches and primitive stop motion trickery to create subliminal flashes of phantom figures – an idea which is used very well, in spite of its simplicity and potential corniness – whilst the ‘echo chamber coal mine’ vibes on the soundtrack just won’t let up. 3/5

Pulp Thrills:

Nothing doing. I mean, it’s the ‘80s, and I doubt the budget here even stretched to lunch money. 1/5

Altered States:

Definitely one of the best latter day expressions of Franco’s patented brand of oneiric Mediterranean psychedelia, ‘Mil Sexos..’ is extremely well photographed, dripping with casually freaked out visual splendour as Jess goes wild with some surprisingly experimental sequences.

In particular, he seems obsessed with textures here, plunging us into patterns of dense foliage (of the floral rather than human variety, for once) as the characters explore a ruined, overgrown walled garden, and he really gets way out towards the end of the film, as the camera takes a lengthy psychedelic journey across a blood-splattered window, revelling in the Pollack-esque patterns smeared against the bright sun-light.

There’s also a brilliant scene in which Lina’s voiceover reads aloud from a pulp horror novel that was presumably lying around whilst they were filming, as the camera cuts between an extreme close-up of her lips and shots of the book’s lurid artwork, depicting a bloody knife clutched between another pair of lips.

All of these stand as great examples of the kind of accidental, improvisatory quasi-genius that Franco scatters through his better films – real otherly inspired bits of filmmaking that make his (admittedly understandable) reputation as a talentless exploito hack seem doubly unfair. 4/5

Sight-seeing:

Shot in Malaga and Gran Canaria (thanks, imdb), ‘Mil Sexos..’ isn’t particularly big on outdoor locations, but it makes excellent use of Andalucía’s Moorish architecture, including an absolutely jaw-dropping tiled courtyard, assorted decorative wrought iron carvings and that aforementioned crumbling walled garden, whilst Franco frames some particularly fine shots around a corridor lined with some distinctive pastel-shaded stained glass windows, in the same ancient-looking building (some kinda lounge / hotel bar?) in which Lina & her husband perform their psychic act. As you might expect, waves crash hypnotically on the soundtrack, gulls call, and, despite the prevalence of interiors, sense of place is strong. 4/5

Conclusion:

Along with the similarly themed ‘Macumba Sexual’, this is definitely one of the best ‘80s Francos I’ve seen thus far. Although clearly derivative of any number of his previous films, solid technique, pungent atmosphere and captivating visuals make it a good effort all round, and a GREAT one for its era.

Sunday, 16 September 2012

FRANCO FILES:

Justine (1969)

Justine (1969)

AKA:

‘The Marquis de Sade: Justine’, ‘Justine de Sade’, ‘Justine & Juliet’, ‘Justine Ovvero le Disavventure Della Virtù’, ‘Les deux beautés’, ‘Deadly Sanctuary’.

Context:

The financial backing provided by maverick producer Harry Alan Towers allowed Jess Franco to produce some of his best ever work during the late ‘60s, but also resulted in some of his worst. Unfortunately, ‘69’s ‘Justine’ falls soundly into the latter category. Budgeted as a modest historical epic, featuring numerous familiar faces and running to an interminable 125 minutes, the film is a total misfire, perhaps the biggest blunder in either man’s catalogue (which is saying something).

Set in France and filmed in Spain with the cast speaking Italian, with an English producer and funding from West Germany, Liechtenstein and the USA, it is at least a great example of the way that Jess Franco films began to completely defy any idea of national identity, but sadly little of this variety is visible on-screen.

Content:

Apparently the intention here was to reinvent the Marquis DeSade’s philosophical novel ‘Justine’ as a kind of ‘Tom Jones’-esque bawdy romp, with Romina Power (a charisma-free young actress whom Franco claims was ‘imposed’ upon him by Towers) in the title role as the virtuous convent girl whose moral scruples land her up to her neck in cruelty, poverty and vice, whilst her amoral harlot of a sister (Maria Rohm) by contrast does very nicely for herself.

Applying such light-hearted treatment to such ponderous source material is a questionable decision at best, and, whilst I’m no fan of DeSade, even I can recognise that the banal episodic shenanigans and jaw-droppingly crass moralistic ending that Franco and Towers come up with here is a complete travesty of his work.

Amongst the roll-call of should-have-known-better thespians taking a deep sigh and collecting a cheque that probably bounced, the great Mercedes McCambridge (Johnny Guitar, Touch of Evil) plays a hardened convict who breaks Justine out of jail, and Klaus Kinski turns up to play the Marquis in a framing narrative that supposedly sees him penning the novel from his cell in the Bastille. In keeping with his other performances for Franco, Kinski essentially earns his pay by doing nothing whatsoever, sitting around in a powdered wig, looking bored out of his skull as somebody else (I think it might actually be Jack Palance?) intones his voiceover narration.

And speaking of Jack Palance, the movie’s sole saving grace (and the only bit that actually seems much like a Jess Franco movie) comes when Justine falls into the hands of a sect of sex-mad libertine monks led by Palance, who gives every indication of being smashed out of his gourd, delivering a truly crazed performance that must rank as one of the best/worst (delete as applicable) that the great man ever subjected us to during his years in Europe. For one scene that calls for him to walk from one location to another, he seems to have refused to move, and is instead inexplicably wheeled across the screen on some sort of cart as he stands motionless, with his hands raised in a kind of Nosferatu-like ‘doom claw’ posture. Damnedest thing I ever saw.

Kink:

For a project that ostensibly sees a meeting between Jess Franco, a bunch of money and The Marquis DeSade, I’m sad to report that ‘Justine’ is staggeringly un-erotic. You get some dream sequence flogging during the Kinski scenes, intermittent boobs elsewhere, but beyond that we’re in ‘sizzle not the steak’ territory here really. Dated nudge-wink type crap and tame jabs at authority that might have passed for ‘satirical’ in the 1780s predominate, and Jess only seems to work up any real enthusiasm during a brief visit to Jack Palance’s sex dungeon, where we get to witness a bit of sexy acupuncture (a motif that was to turn up again in a number of Franco’s later, more explicit films), spilling over into a super-imposition heavy psychedelic montage and… wow, I just typed the words “Jack Palance’s sex-dungeon”. But I’m afraid I’m still only giving this 2/5.

Creepitude:

Nothing doing. Admittedly, it’s not supposed to be a horror film, but by the standards of any genre, much of the movie is blandly photographed and horribly over-lit, and although the production seems to have a bit of cash behind it, most of the sets and costumes still end up looking like a West End musical. Again, best advice is to fast forward straight to the Palance section, which at least has cool lighting and echoy psychotronic music, and Howard Vernon smirking in a really terrible wig. 1/5

Pulp Thrills:

Perhaps if for some reason you’re totally obsessed with powdered wigs, hoop dresses and second rate 18th century bawdiness, you might get some fun out of this…? If so, I wish you all the best. Just in general. 1/5

Altered States:

The only psychotropic effect you’re likely to experience during ‘Justine’ is unquiet sleep, haunted by candy-coloured annoyance. Did I mention it’s over TWO HOURS long..? Christ. I know from my descriptions above it maybe kinda sounds like fun, but even by Franco standards this thing drags like a bastard. 1/5

Sight-seeing:

Much of the film is shot on sets, and pretty dodgy looking ones at that. In between however, we can at least enjoy some extensive location work in and around Barcelona, with Franco presumably using the clout that accompanies a modestly budgeted historical epic to shoot beside the fountains in the Parc de Montjuïc and the magnificent frontage of the Palau Nacional, in addition to the more traditional b-movie surroundings of a ruined abbey, a clifftop fort masquerading as a Parisian women’s prison and… oh look, a beautifully strange looking Gaudi-designed folly/gatehouse type thing! Bonus points for that. 3/5

Conclusion:

A textbook example of the way that period settings, literary subject matter and relatively big budgets stymied Franco’s creativity, his direction here is workmanlike at best, so lacking in all the things that usually make his films enjoyable, he might as well have not even bothered turning up. I mean, there are better people to hire if you just want someone to point the camera in the right direction, y’know?

Franco completists and those who’ve picked this up on one of the Anchor Bay box-sets might want to give it a go for the Palance sequence, which is a pretty good laugh with a few recognisably Franco moments, but aside from that, this is an extremely poor effort, and even a score from the usually reliably bad-ass Bruno Nicolai turns out to be overblown orchestral rubbish. Offered a choice between watching this and reading the book, my money’s on doing neither and just listening to The Rangers song a hundred times.

Sunday, 9 September 2012

A Woman After A Killer Butterfly

(Kim Ki-Young, 1978)

(Kim Ki-Young, 1978)

Watching Kim Ki-Young’s 1978 film ‘Woman After A Killer Butterfly’* for the first time is likely to be a fairly strange experience for any viewer. But for those of us watching it ‘blind’, as it were – with no prior knowledge of the director’s work, or of his place within Korean cinema – it’s gonna be a real a real doozy. An 8.5 on the weirdo richter scale, call-the-WTF-police, high level freakiness jamboree. You know the deal, I’m sure.

You also know, presumably, that nine times out of ten when the shadier end of international horror/fantasy cinema throws up what appears to audiences in the English-speaking world to be an A grade piece of mind-blowing bafflement, such impressions can be primarily attributed to cultural differences, general ignorance on our part and a failure to appreciate the limitations and conventions within which these marginal filmmakers were working. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, I hasten to add – it’s just the way things are, all part of the fun as we stumble our way through uncharted cinematic territory.

What is far more interesting however is that one time out of ten when things get strange in a way that is genuinely unaccountable, and what we’ve got here is a case in point. Because rather than the unhinged, culture clash style weirdness one tends to associate with Asian movies, ‘Killer Butterfly’ is an intelligent, self-aware, extremely well made and internationally informed film that just happens to be… completely inexplicable.

My reason for bringing all this up is simply that what with the film (and several other of Kim Ki-Young’s key works) suddenly being available to view on Youtube courtesy of the Korean Film Archive, it seems likely that ‘Killer Butterfly’ will sooner or later be turning up alongside ‘Mystics in Bali’ and ‘Housu’ on somebody’s list of ‘Top Ten Crazy-Ass Loony Asian Horror Films That You Gotta See’ or somesuch - an inclusion that even the slimmest amount of research (and that’s all I’ve done, needless to say) would reveal as both undeserved and deeply inappropriate.

First off, ‘Killer Butterfly’ isn’t really a horror film. With its wealth of grotesque gothic imagery and supernatural happenings, it could easily be mistaken for one, but no... it's true intentions lie somewhere else entirely. At a push, you could maybe claim it as a ‘fantasy’ film, but again, none of the elements we’d associate with such a tag are really catered for. Although Kim Ki-Young certainly delights in playing with genre elements, at the end of the day ‘UNCLASSIFIABLE’ is the only drawer you’re really gonna be able to file a film like this in. But more on that later.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, Kim Ki-Young’s background and career is about as far removed from that of yr average regional lo-fi horror maniac as it’s possible to get.

Spending time in Japan after WWII, he became a devotee of American and European cinema, and gained his first experience of film-making producing newsreels for the US army during the Korean War, after which he was in on the ground-floor of South Korea’s own national cinema, shooting his first features (including the country’s first film with synchronised sound) on equipment he’d requisitioned from the Americans. Working solidly through the late ‘50s on neo-realist style films and social melodramas, he could very much claim to be one of the founding fathers of his country’s film industry, and proceeded to follow the path of an independent minded auteur/arthouse filmmaker as closely as circumstances allowed. Critical plaudits and relative financial success in South Korea ensued, and it was only after his international ‘breakthrough’ film – 1960’s ‘The Housemaid’ – that controversy began enter the picture.

Apparently, ‘The Housemaid’s outbursts of expressionism and Bunuel-esque subversive turmoil marked a shocking departure from the strain of optimistic realism that had until then predominated in Korean cinema, and, following the film’s success, the director pushed further toward what is described as his ‘mature style’ during the ‘60s – a style that his reassuringly informative Wikipedia page describes as being characterised by “..gothic excess, surrealism, horror, perversions and sexuality”. Our kinda guy, in other words!

When the Korean film industry (along with most other national film industries) hit the ropes during the ‘70s, Kim began to produce his films independently, with the financial assistance of his wife (a successful dentist) allowing him more freedom than ever before to indulge his eccentric tastes, resulting in a series of ambitious films that, despite a sizeable cult following and a surprising level of box office success, seem to have been met with what I can only assume was a sense of bafflement and indignation from the rest of the Korean film industry – at least if the near complete absence of this venerable and prolific director from the country’s annual ‘Blue Dragon’ and ‘PaekSang’ awards ceremonies, and the corresponding low profile of his films overseas, is anything to go by.

Returning to ‘Killer Butterfly’ with this background in mind, it all begins to make a bit more… well, not sense exactly, but its existence becomes more understandable, let’s put it that way.

As Todd of Die, Danger, Die, Die, Kill! observed when he reviewed the film a few months back, the only way to successfully convey the alien logic of ;Killer Butterfly' is via straight plot description. Normally I’d prefer to avoid such synopsis-heavy reviewing, but sometimes (as with Alabama’s Ghost, for example) I’m afraid it’s the only way to go. So, if you’re sitting comfortably, let’s begin.

Young-gul (Kim Chung-chul) is a nervous young medical student, who is enjoying a day out in the countryside pursuing his favourite hobby, catching butterflies. As he spikes one of his specimens with a syringe, a well-dressed woman approaches him and begins haranguing him for his cruel treatment of the creatures. “When it comes to death, people are no different, it’s just as trivial” she argues, rejecting Young-gul’s assertion that the death of a human is “much more noble” than that of an insect. The two apparently agree to disagree, and the woman offers Young-gul a cup of juice, which he accepts. Only when it is too late does she reveal that the juice is in fact poisoned, explaining that she had come to this remote place to die, but didn’t want to enter the afterlife alone.

Freaking out as he collapses into a coma, Young-gul subsequently awakes in hospital, where a rather slack police inspector informs him that the woman did indeed die, throws him her butterfly pendant as a memento, and lets him go free. Arriving home (he seems to live in a squalid mountainside shack, somewhat reminiscent of the one where all that crazy shit goes down in the second ‘Female Prisoner: Scorpion’ film), Young-gul finds himself plunged into a deep depression by the incident, and, feeling there is a now “poison in his soul”, decides to kill himself.

Young-gul’s suicide is interrupted however by an elderly travelling bookseller, who repeatedly barges his way into the shack, proffering copies of a book extolling the virtue of ‘strength of will’, a creed which the man insists can inspire one to immortality. Enraged by this cackling weirdo upsetting his solemn date with death, Young-gul eventually stabs the man with a kitchen knife, but, mortally wounded, he continues to jabber on, even as his blood drains away and his heart stops beating. Tiring of the now undead man’s continuous diatribe and the smell of his decomposing body, Young-gul sets out to bury him, and, when he returns from his shallow grave still preaching the virtues of willpower, to burn him. Following his cremation, the old man returns yet again as a walking, talking skeleton, who beats Young-gul with his bony arms, laughing at him and mocking his desire to die. A gust of wind enters the shack and reduces the skeleton to ash, but the old man’s disembodied voice raves on, proclaiming that his spirit will live on forever, as his essence drifts off on the winds.

Apparently impressed enough to take the old man’s advice for the moment, Young-gul puts his suicide on hold and returns to college, where a buddy of his convinces him to help out with a unique money-making scheme. Visiting a complex of caves, they break off from the guided tour and sneak out with the bones of an ancient skeleton, that Young-gul’s friend has arranged to sell to Dr. Lee, a prominent archaeologist, for a healthy profit. Left alone to assemble to skeleton in his shack, Young-gul is… well I was going to say astounded, but actually he seems to take it in his stride… when the skeleton regrows its flesh, assuming the shape of a beautiful, pale-skinned woman, who explains that she had fled into the caves 2,000 years ago, using Shamanic magic to keep her spirit in limbo until ‘the right man’ – that presumably being Young-gul – stumbled across her bones and resurrected her.

Unfortunately, if Young-gul’s ancient bride is to retain her corporeal form, the Shaman’s spell decrees that she must eat a raw human liver within ten days, or else return to a sack of inanimate bones. Refusing to hunt down a liver for her, Young-gul tells her she’ll have to find one herself, leaving her complaining of her unquenchable hunger as she eyes up the liver of her prospective husband…

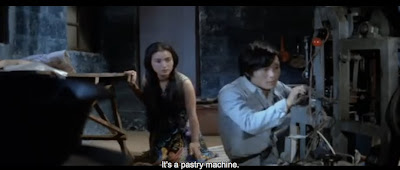

How will this unsettling drama play out? Well we won’t find out quite yet, because some men have arrived at the shack, carrying a large piece of industrial machinery. “What’s that?”, the 2000 year old woman asks. “It’s a pastry machine!”, Young-Gul replies. “I thought we could use it to make some money on the side”.

Aaand, that’s where we’re going to have to leave our extended plot synopsis for the moment. So far, I’ve only covered about the opening forty minutes of ‘Killer Butterfly’s two hour run time, but… the pastry machine. It’s too much. You’ll just have to watch it for yourself and find out.

Actually, in a certain sense, this kind of high weirdness, that makes the film so noteworthy for jerks like me, kind of works against its overall artistic success in some ways. I mean, in essence, ‘Killer Butterfly’ is sort of a classical tragedy that tries to tackle weighty cosmic issues of life and death and rebirth etc. But after watching it, all I could think was, jesus christ… the pastry machine.

Anyway, after this apex of grand strangeness is over and done with, the film finally breaks away from the random, episodic anti-narrative that has prevailed thus far, and settles down (in a manner of speaking) into merely an intense gothic melodrama with a sub-plot about a secret society who dress up as butterflies to desecrate graves and send severed heads to a renowned archaeologist (or something).

In brief, Young-gul shrugs off the 2,000 year old woman caper, and takes up a job as assistant to the aforementioned Dr. Lee, moving into his richly appointed home and becoming involved with his equally death and butterfly obsessed daughter Kyungmi (Kim Ja-ok), with the pair’s chaste and tempestuous non-relationship proceeding to dominate the remainder of the film.

Whilst the preceding scenes have been characterised by an unmistakable strain of knockabout black humour, from hereon in things become more tricky to interpret, as the film strikes an uneven balance between metaphysical earnestness and grotesque genre parody that often becomes quite offputting.

Is Kim Ki-Young genuinely trying to make some grand, Jodorowsky-style Point about life and death, being and nothingness here? The intensity with which he treats these scenes in which characters yammer on and on about the solace of death and when and why they intend to put an end to their bleak existence, and the commitment of Ka-ok and Chung-chul’s startling performances as the doomed un-couple, certainly suggests as much, recalling the uncompromising emo-turmoil of heavy hitters like Zulawski’s ‘The Devil’ (1973) and Sion Sono’s ‘Love Exposure’ (2008).

But at the same time, this stuff is just ploughed through over and over, raised to such an absurdly heightened pitch of melodramatic silliness, it simply CANNOT be taken seriously, often verging onto some epic pastiche of the brand of melodrama that holds a central place in Korean film & TV. As noted, Kim Ja-ok’s performance is astonishing, but her character’s hand-wringing, self-obsessed Young Werther style angst soon becomes absolutely interminable, as does Young-gul’s impotent terror of the world around him, and Dr. Lee’s laughably overblown macho dedication to his daughter. And meanwhile, the whole far more interesting (to me at least) business of the butterfly-masked graverobbing cult remains sadly unexplored.

There IS undoubtedly a strong element of absurdist comedy running through the film - in contrast to the later reels, the whole 2000 year old woman section is both hilarious and strangely touching, and the film’s ‘horror’ bits have a great Evil Dead/Sammo Hung slapstick feel to them. But as things get more overwrought, the script’s uneasy blend of parody and pathos makes it very difficult to really get an angle on where Kim Ki-Young is coming from with all this stuff, emotionally speaking.

Where he’s coming from visually speaking is at least a lot clearer, as ‘Killer Butterfly’ gleefully draws on recognisible horror imagery throughout, with skulls and skeletons and candelabras and gothic hoo-hah infesting just about every frame, as the film rambles back and forth across the boundaries of life and death. It’s difficult to ascertain whether or not the influence of European horror is deliberate, but as fans of such things will no doubt have already noticed from the screengrabs accompanying this review, ‘Killer Butterfly’s dense, hyper-real colour scheme certainly has a lot in common with the more imaginative gialli, and the brooding fantasias and unnatural light sources of Mario Bava’s early/mid ‘60s work in particular.

Very much unlike a horror film however is ‘Killer Butterfly’s unhurried, leisurely pace, as the film strays freely from any kind of narrative tension with the freedom that becomes a filmmaker unchained from commercial necessity, as wholly tangential scenes – a beach party, a visit to the hospital – are transformed by Kim Ki-Young into outlandish tone poems of sumptuous colour and texture that are a joy to behold, even when the action on-screen becomes repetitive or incomprehensible. In fact, as the film progresses, this uniquely expressive approach to cinematography (which doesn’t exactly make for easy viewing on youtube, it must be said) seems to reflect the story’s obsessive concern with the battle between life and death, as bright patches of vivid, burning colour are consumed amid an ocean of impenetrable, inky blackness – an idea that is arguably conveyed far more powerfully through the visuals than it is through much of the script.

A horribly glib comparison perhaps, but after looking over Kim Ki-Young’s CV and watching a few of his films, I can’t help but think that discovering his work is a bit like stumbling across the Korean David Lynch. Clearly both are hugely talented and ambitious filmmakers who can command a strong popular following (Kim was apparently awarded the nick-name ‘Mr. Monster’ by his fans) and could easily sit at the forefront of their respective national industries, were it not for their insistence on producing films that many critics deem maddeningly eccentric and excessive – bulbous, overbearing, upsetting and impossible works, but never less than wholly original, with a strong streak of untamed genius always running wild.

With this in mind, perhaps the best way for us Westerners to explain the singularity of something like ‘Killer Butterfly’ is to say that watching it is a bit like taking someone who’s largely ignorant of American cinema and beginning their education by showing them ‘Lost Highway’ or ‘Mulholland Drive’ – an overwhelming and disorienting experience to say the least, but, given the chance, who amongst us wouldn’t want to dive straight in and savour the madness?

*Some sources go for the simpler English title of ‘Killer Butterfly’, whilst the film’s own subtitles identify it as ‘Chasing the Butterfly of Death’, and English text on the Korean poster states ‘Woman With Butterfly Tattoo’. So make of that what you will.

Wednesday, 5 September 2012

Penguin Crime Week:

Death at the President’s Lodging

by Michael Innes

(1962)

Death at the President’s Lodging

by Michael Innes

(1962)

(Cover photograph by Paul Gori)

Don’t have much to say about this one, but, um… here ya go. I like the rounded corners at the bottom of the photo. Also, skeleton!

The green on the back looks a bit toxic, doesn't it?

Monday, 3 September 2012

Sub-Machine Gun.

A great honour was bestowed upon me this weekend, as renowned blogging polymath Unmann-Wittering (Island of Terror, Mounds & Circles, This Is Not The Universe) invited me to contribute to a new weblog.

The idea is simple: sub-titled screengrabs in all their surreal, puerile, beautiful glory. Posted one per day, and continuing up until such a point as people in foreign language films stop saying ridiculous things, and long-suffering translators cease typing them over the top in English.

Pointless? Simple-minded? Yeah, probably, but I know I never cease to get a kick out of the strange word/image disjunction that out-of-context subtitles can provide us with, and I hope you can enjoy it on some level too.

As far as my own contributions go, there’ll likely be a few that I’ve posted here in the past, a few ‘greatest hits’ from my tumblr, and a lot more that I’ll be posting for the first time.

Sunday, 2 September 2012

Penguin Crime Week:

The Half Hunter

by John Sherwood

(1961)

The Half Hunter

by John Sherwood

(1961)

(Cover design by Sheila Perry.)

Well you had me at “ice-skating beatniks”. Might have to give this one a try too.

Not sure what the big black square on the back is all about..?