Yes, I know this has taken a while. Apologies again for the delays in posting.

Hard-boiled Brit-crime thuggery goes toe-to-toe with Joseph Losey’s self-conscious cinematic artistry in this fascinating UK gangster-noir, which I wrote about at length back in August.

One of the more comparatively upbeat films made about the prospect of nuclear annihilation, Ray Milland’s directorial debut finds him starring as a stuffy, suburban dad who, having cajoled his family into hitting the highway before sunrise to beat the traffic en route to their annual camping holiday, glances in the rear view mirror just in time to see a H-bomb obliterating Los Angeles.

Within minutes, upstanding family man Ray is busy securing his all-important supplies (two bags of flour, a dozen pounds of coffee, a can of ‘shortening’, whatever that is) and shop-lifting some firepower from a nearby hardware store. Before long, he’s throwing flaming barricades into the middle of busy highways to make a path for his own vehicle, punching out uncooperative gas station attendants, and insisting his wife and daughter stay out of sight in the camper van, whilst his JD-ish teenage son (Frankie Avalon!) - who seems totally delighted by the emergence of Action Dad - rides up front to provide muscle and covering fire for his old man.

I don’t know what it says about me, but I got a tremendous kick of watching this one at the start of last year. Whilst it certainly doesn’t shy away from depicting the downside of total societal collapse (banditry, rape, paranoia, hunger, lack of basic medical care), incongruous bursts of jaunty, big band jazz and Milland’s unflagging determination to make the best of things nonetheless make the whole wretched business seem weirdly appealing.

Full of minor absurdities and rich in dialogue which has assumed an additional, blackly comic weight in recent years, if you’re looking for a movie to temporarily make the earth’s current sorry state feel just a little bit more manageable, Big Ray’s got your number. For as the man himself says;

“Now we don't know what lies ahead of us. The unknown has always been man’s greatest demoraliser. Now maybe we can cope with this by maintaining our sense of values, by carrying out our daily routine, the same as we always have. Rick, for instance, and myself will shave every day... although in his case, maybe every other day. These concessions to civilization are important. They are our links to reality, and because of them we might be... less afraid.”

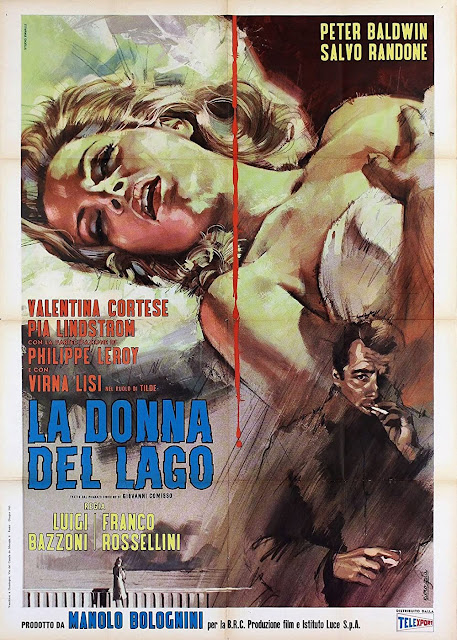

Moderately weird and exceptionally atmospheric, this oneiric artefact from the golden age of Italian gothic horror had somehow escaped my attention until last year, but I’m very happy to have rectified the situation - as my full length review from October will hopefully attest.

It may take a while for the action to really kick off in this second sequel to Jackie Chan’s epochal ‘Police Story’ (1985), but in the meantime, the tale of Chan’s hapless Ka Kui being dispatched to the Chinese mainland, and later to Kuala Lumpur (where permits for city-wide destruction were easier to obtain, I supposes), pairing up with PRC super-cop Michelle Yeoh to combat the obligatory propagators of nefarious, drug-smuggling villainy, proves likeable enough.

When the expected acrobatic/ automotive armageddon eventually does get going though, holy hell, it is extraordinarily unhinged stuff, even by the standards of Jackie’s late 80s/early 90s imperial phase. Pretty much everything but the kitchen sink gets thrown in here somewhere, from straight up kung fu duels to high velocity car/bus stunts, prison breaks, Rambo-esque machine gun / exploding hut action, death-defying urban helicopter dangles, ‘Project A’ style back alley chases… but the eventual finale (staged atop a speeding train) is simply beyond belief. (If you have fifteen minutes to spare, why not treat yourself by reliving the entire sequence of events via youtube?)

We must, I suppose, salute the dedication to punctuality exhibited by the unseen Malaysian train driver who declines to slow down or take emergency measures, even though a helicopter has crashed into his train, but that aside, MVP status here definitely belongs to Yeoh, who keeps pace with Jackie throughout, and, in the film’s ultimate pièce de résistance - a staggering dirt bike-to-moving train jump - becomes the only co-star to ever upstage him in one of his own classic era films. Respect is due.

I’ve been receiving smoke signals for years re: what a good film this is, and, yes, it is indeed an excellent, bitterly heartfelt piece of work. But… shit, it is ever a difficult one to write about.

Though ostensibly a neo-noir / crime story, Passer’s film (based on Newton Thornburg’s 1976 novel ‘Cutter and Bone’) is really more concerned the psychic aftermath of the Vietnam war, and, more broadly, the plight of the people - be they boat-dwelling gigolos, disabled war vets or habitual alcoholics - who fall through the cracks of nine-to-five American life, and suffer for it.

Alongside the shadow of the war, the long hangover from the ‘60s also hangs heavy over the world inhabited by these characters. The promise of new freedoms offered by that decade has congealed, very badly indeed, for those naive enough to take it seriously, whilst, close enough to touch yet a million miles distant at the other end of the beach, the representatives of the previous generation’s Old Money (and even older power) return to circle, shark-like - cold, callous, and just waiting to put the bite into whoever stumbles across their path.

More than anything, I found this vision simply sad as hell, offering little light beyond the self-medicating fog, with John Heard’s feverish performance as Cutter in particular leaving the viewer feeling hallowed out from within, unable to shake the second-hand pain and guilt.

SO HEY -- let’s take a different tack instead. I’m not sure if this little cinematic conspiracy theory of mine has already been extensively discussed elsewhere, but… an unlikely friendship between an aimless slacker played by Jeff Bridges and a bitter, argumentative Vietnam vet? Who both become haplessly embroiled in a criminal intrigue involving a philanthropic millionaire…? You can see where I’m going with this, right? Not to take anything away from a certain comedic masterpiece made by a pair of idiosyncratic filmmaking brothers some fifteen-odd years later, but, drastically tweaked tone aside, the similarities here are striking.

Though they’ve long been a cult concern amongst cinephiles, the series of inauspicious western programmers made by director Budd Boetticher and star Randolph Scott in the late 1950s were a new discovery for me in 2021 (driven by the oft-affordable standalone releases now offered by the Indicator label). I’m still slowly working my way through them, but this one - the first in the sequence - stands as my favourite thus far.

Elevated far above the level of a standard oater by Boetticher’s suspenseful, minimalist direction (cutting and moving figures within the frame like a b-Western Kurosawa), by the surprising psychological nuance and moral ambiguity of Burt Kennedy’s script (the fact it was based on an Elmore Leonard story probably helped), and by fine, appropriately taciturn performances across the board (including an early turn from Henry Silva as one of the villain’s goons), ‘The Tall T’ basically is basically the Platonic ideal of a perfectly formed low budget western.

Despite being saddled with a disspiritingly bland/meaningless title when presented to English-speaking audiences, ‘Silent Action’ (or, THE POLICE ACCUSE: THE SECRET SERVICE KILL, as I prefer to call it) stands for my money as by far the best film Sergio Martino ever made in the crime genre. [Full disclosure: I’ve not yet seen his 1974 film ‘Gambling City’, so can't speak for that one.]

Essentially playing out like a 50/50 hybrid between a pulpy ‘tough cop’ poliziotteschi and the kind of tonally serious, politically engaged thrillers that directors like Sergio Sollima and Damiano Damiani were making at the time, this film (nobly resurrected on blu-ray last year by UK-based label Fractured Visions) presents a somewhat challenging tonal blend which Martino - frequently underrated for his genre-splicing talents - pulls off with aplomb.

On the one hand, the movie is fast-moving, action-packed and full of familiar Euro-crime clichés. But at the same time, it never gets too cartoon-ish or implausible, and never plays its audience for fools, instead working out a specifically Italian take on the kind of paranoid / conspiratorial plotting popularised by films like ‘The Parallax View’ and ‘The Conversation’ in the preceding years. Mercurial as ever, Martino even gives us an outburst of full on ‘exploding hut’-style war movie craziness in the final act, which is… unexpected, but fits in surprisingly well.

Released in the midst of the craze for ‘Dirty Harry’/‘Death Wish’-inspired vigilante fantasies, ‘Silent Action’ is also interesting as an example of a poliziottescho which comes down firmly on the left wing side of the political spectrum, with Luc Merenda’s rule-breaking, two-fisted cop finding himself essentially fighting against corporate/state collusion and the spectre of resurgent fascism - issues which must have hit close to home for many viewers during Italy’s turbulent 1970s.

I picked this aptly named motion picture up as a blind buy last year, after watching the trailer Vinegar Syndrome put together for it, and I’m very glad I did, for it brought great joy unto my household.

A one-shot independent production, ‘Action U.S.A.’ was convened in the unlikely environs of Waco, Texas by a group of professional stuntmen who had seemingly grown tired of working within the stifling confines of Hollywood (and, one suspects, its equally stifling health and safety protocols). The film’s plotline involves a pair of mismatched FBI agents and the super-hot girlfriend of a deceased drug dealer teaming up to undertake a state-wide boondongle in search of a cache of stolen diamonds, and it is goofy to the nth degree, in a hugely likeable way. As to the titular action meanwhile, well - much as you’d hope, it is relentless, impeccably shot and choreographed and totally out to lunch.

Beginning with an extended helicopter dangle which makes Jackie’s one in ‘Supercop’ (see above) look like a fucking joke, the film proceeds to wreak more havoc upon Texas’s highways, urban intersections, abandoned buildings and second hand cars than an entire century’s worth of tornados, alongside all the secondary damage you’d expect to see inflicted upon crotches, jaws, footwear and so forth. Also featuring country n’ western (live), hair metal (on tape), footage of Cameron Mitchell yelling into a brick-size mobile phone whilst sweating on a treadmill, and a gravel-gargling, machine gun-toting William Smith (R.I.P. big man) as the Chief Bad Guy.

What more, I ask you, could you possibly ask of a movie named ‘Action U.S.A.’?

Being a relative newcomer to the ways of kung fu, I’d never previously seen this epochal Shaw Bros production, which, as ‘Five Fingers of Death’, became the first martial arts movie (indeed, quite possibly the first Asian movie, period) to make a significant impact at the U.S. box office.

The reasons for the film’s ground-breaking success are clear to see, even today. Due perhaps to the fact that director Cheng Chang Ho was both Korean and also not a Shaw company man, ‘King Boxer’ feels more straight-forward and universal in its appeal than many of the Shaolin sagas which followed in its wake through the ‘70s. As well as ditching much of the convoluted plotting and culturally specific esoterica which can make Shaw Bros pictures a hard sell for Western audiences, Ho also seems to have encouraged his cast to perform in an emotive, conventionally melodramatic manner which immediately sets the film apart from the stiff / formal approach favoured by directors like Chang Cheh.

Though the film’s fight choreography remains convincingly bad-ass, Ho also seems less concerned with the extended demonstration of traditional techniques than his fellow Shaw directors, breaking up the moves with jump cuts and close-ups, and employing the vocabulary of spaghetti westerns (crash zooms, extreme close-ups and long, tension-building camera moves) to bring a delirious sense of operatic / pop art intensity to proceedings.

Excitement is further heightened by the addition of some gloriously crimson, proto-‘Street Fighter’ gore, and of course, the fantastical elements which lend the film it’s most indelible imagery, as Lo Lieh’s strangely beautiful hands glow red with diabolical power, accompanied by an unforgettable, fuzz-drenched electronic musical sting (purloined from, of all things, the intro to Quincy Jones’ theme from ‘Ironside’!)

The seasoning on the chow mein (if you will) though is the film’s cinematography and production design, which is absolutely splendid, mixing dense, detailed sets with extensive use of deep focus and that very particular kind of rich, vivid colour found in only the very finest ‘60s genre films (you know, deep inky blacks and searing, carefully picked out blasts of red/blue/green - think Mario Bava basically). Combined with the other virtues outlined above, ‘King Boxer’ stands as an example of unpretentious, grindhouse-era action cinema reaching dizzy heights of iconic pop artistry.

The directorial debut of Luigi Bazzoni (who went on to make the equally compelling ‘The Fifth Cord’ (1971) and ‘Le Orme’/’Footprints’ (1975)) and Franco ‘nephew of Roberto’ Rossellini (who didn’t), this is another under-appreciated Italian oddity which seems to have fallen through the cracks separating that nation’s arthouse and popular cinemas.

In terms of the latter, the film does boast a somewhat giallo-ish plotline about a troubled young novelist (Peter Baldwin) travelling to an off-season lakeside resort to investigate the death of a hotel maid with whom he had previously had an affair…. but beyond that, it heads straight out into uncharted stylistic waters and never really returns.

Essentially a mood piece, ‘La Donna Del Lago’ is defined by an intangible sense of wrongness which pervades the very air of its remote, wintry location. A mood of weird, almost supernatural, dread seems to hang over the spaces Baldwin explores and the people he encounters, diverting his rather lacklustre investigation into dreamlike, symbolic terrain from which his lonely soul seems unlikely to emerge intact. Or, to put it more simply: ‘Twin Peaks’ vibes to the max.

Though the resolution to the mystery is ultimately fairly prosaic, it is Bazzoni & Rossellini’s decision to concentrate not on the events themselves, but on the psychic detritus and unreliable memories which surround them, which really sets the film apart. Beautifully crepuscular monochrome photography from Leonida Barboni, erotically-charged avant garde daydream sequences and suitably oblique, troubling performances from an extraordinary supporting cast (Valentina Cortese, Salvo Randone, Virna Lisi, Philippe Leroy) all very much help in this regard too, helping ‘La Donna Del Lago’ stand out as one of the most haunting, off-beat and weirdly harrowing thrillers to have emerged from Italy during the ‘60s.

To be (eventually) concluded…