Though the fatalism and alienation which subsequently became recognised as signifiers of the ‘noir’ worldview remained intact, the work-a-day, proletarian outlook of these post-war crime flicks in some sense harked back to the Warner Bros gangster epics of the early ‘30s, albeit with an aspiration toward ‘documentary realism’ supplanting the snarling, comic book mayhem proffered by Cagney and Robinson.

With its ground-breaking use of authentic urban location shooting, Jules Dassin’s ‘The Naked City’ (1948) is often held up as the ‘trigger film’ for this wave of ‘realist’ noir, but by that point the trend already seems to have been well underway around the margins of the industry by the time Anthony Mann laid down the preceding year’s ‘T-Men’ for freelance producer Edward Small.

Released outside of the studio system by distributor Eagle-Lion, this remorselessly glum tale of two undercover U.S. Treasury agents infiltrating a Detroit crime syndicate in order to help take down a Los Angeles counterfeiting operation is about as ‘procedural’ as a crime film can possibly get whilst still retaining the essence of noir.

So entirely unencumbered by movie-world glamour is its utilitarian world of men in hats taking care of business in fact, it could easily have been mistaken for a crudely staged re-enactment of factual events, or an instructional film for trainee federal agents, were it not for the presence of a few ‘larger than life’ character types, and, more importantly, of John Alton’s extraordinary, expressionistic photography.

Perhaps a direct result of its quasi-realist aesthetic, ‘T-Men’ is unfortunately also a deeply schizophrenic motion picture, and not in a good way.

Let me put it to you this way: most fans of Production Code era Hollywood will be familiar with the phenomenon of the ‘tagged on ending’, a device particularly common to crime films and thrillers, wherein some comfortingly square authority figure tends to pop up after the story’s hair-raising drama has concluded, reassuring us that all evil-doers were inevitably brought to justice by the benign powers of the law and judiciary, and that we can all return to their homes for a sound night’s sleep, unmolested by the black-hearted rogues they’ve just seen tearin’ it up on screen for the past eighty minutes (and by extension, unconcerned about the social pressures and inequalities which created them in the first place).

Meanwhile of course, we can practically see the film’s director and writer just off screen, laughing into their sleeves and making “nothin’ to do with me buddy” gestures, confident that any halfway intelligent viewer will grok that the REAL movie ended a few minutes beforehand, with the tragic antihero expiring in a gutter with police lead in his back.

Variations on this theme include the ‘glib happy ending’, the scene-setting, ‘story-you’re-about-to-see..’ prologue and the thunderous, explanatory voiceover, and they’re basically all just a part of the accepted toing and froing which allowed filmmakers to get their visions somewhere near the screen during the first half of the 20th century. Usually this stuff doesn’t do a great deal of damage to the movie itself – it remains fairly self-contained, and can be tuned out without too much difficulty… but boy, is ‘T-Men’ ever an exception.

Let me say straight-up that if Mann had been able to make the film as a tight, sixty-minute programmer about a couple of double-agent hoods taking down a counterfeiting racket, it would have been pretty great picture – a full strength draught of hard-boiled badassery, and a pretty much perfect exemplar of the post-war b-noir form.

Padded out to eighty-six minutes though, filled with blandly-shot visits to the hard-working back office boys in Washington and ham-fisted testimonials praising the moral righteousness and ruthless efficiency of the U.S. Treasury (“there are six fingers of the Treasury Department fist, and that fist hits fair, but hard,” some functionary behind a mahogany desk absurdly informs us at one point), together with voice-of-god narration constantly crashing in to reiterate plot points and remind us of our undercover protagonists’ patriotic, crime-fighting duty and…. well, let's just say the film’s impact is somewhat compromised, to put it mildly.

Imagine watching a version of ‘Psycho’ in which Simon Oakland’s psychiatrist character kept popping up in the middle of the story to calmly talk us through Norman Bates’ thought processes and to reassure us that everything will turn out ok, and you’ll get an idea of what a frustrating viewing experience ‘T-Men’ can be.

Nonetheless though, the good stuff here is well worth sticking around for. As our ostensible lead, Dennis O’Keefe (who went on to headline in Mann’s classic ‘Raw Deal’ a year later) is such a sneering, heavy-lidded bruiser that it’s hardly surprising the producers (or whoever) felt the need to cram in narration every five minutes reminding us that he’s actually on the side of the tax-collecting angels. (He puts me in mind of a somewhat younger version of Eddie Constantine in the Lemmy Caution movies, if that helps give you a bead on where he’s coming from.)

In fact, it’s easy to imagine a version of this movie – almost certasinly a superior one, from my POV - in which O’Keefe and his associate Alfred Ryder actually are just a pair of freelance crooks trying to muscle their way into an inter-state counterfeiting operation, rather than glorified tax inspectors, but I suppose that Eagle-Lion and/or Edward Small simply weren’t brave enough to foist that kind of cynical, amoral grue upon the Code era American public – assuming that the Treasury Dept weren’t actually covertly financing this picture as a propaganda piece (which seems entirely possible, given how heavy-handed their input seems to have been).

Ryder incidentally is by far the more low-key and reserved of our two undercover men, largely remaining in the shadow of the more charismatic O’Keefe, whilst the knowledge that he has a wife and family back home pretty much puts him on the chopping block from the outset vis-à-vis providing us with the necessary emotional clout to raise the stakes for an inevitable blood-soaked finale.

The film’s earlier, Detroit-set section is pretty straight-down-the-line gangland business stuff, as grim men convene in airless brick basements and back offices to pack crates, smoke cheroots and exchange briefcases, but Mann and Alton bring a dour, smog-choked atmosphere to proceedings which hints at dark deeds and snuffed out lives lurking just around the corner.

Things really get going though once O’Keefe is reassigned to L.A., charged with using a series of unfeasibly vague clues to track down the gang’s West Coast connection, a “shover” of counterfeit notes known only as ‘The Schemer’. (He frequents Turkish steam baths, has a scar from a knife wound on his left shoulder and imbibes a certain brand of Chinese medicinal herbs.)

Once O’Keefe dutifully enters the orbit of the weaselly, eccentric Schemer (broadly but rather brilliantly played by Wallace Ford), things take a somewhat more fanciful turn, as he follows his mark to the Club Trinidad in Ocean Park, wherein he cracks wise with an underworld-savvy hostess/photographer (Mary Meade) whose ostensible job involves her selling snaps of punters back to them, whilst meanwhile acting an all-purpose message centre for the counterfeiting gang.

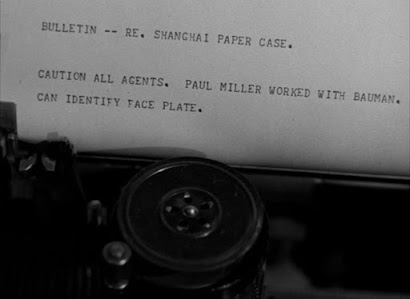

“Tell me, you make a good take shooting mugs like me?,” O’Keefe asks her, before leaving her a message in the form of one of his own tailor-made phony bills, folded just so. This of course brings him to the attention of Mead’s higher-ups in the biz, represented in the first instance by an even more shady technician operating out of the back of a Hollywood photography lab.

Though beautifully rendered by Alton, the assorted scenes of back-stabbing and thuggery which follow, including much procedural details concerning the origins of printing plates and the grading of paper etc, prove less than scintillating, as O’Keefe and Ryder gradually work their way through the ranks toward the head honchos of the counterfeiting racket, one of whom, to our considerable surprise, turns out to be… a dame!Played by Jane Randolph (whom you may recognise as the “Alice” character in both ‘Cat People’ (1942) and its sequel), ‘Miss Simpson’ is admittedly only ‘secretary’ to the actual Big Boss (who keeps a low profile behind a locked door), but she still seems to be largely in charge of day-to-day operations, and finding a woman in a position of authority in a film as unrepentantly masculine as this one is such an unexpected development it feels almost deliberately perverse.

In fact, it’s curious to note that whilst the two female characters in ‘T-Men’ are only on screen for probably about five minutes in total, they are both interesting, unconventional figures, playing important roles in the movie’s criminal infrastructure whilst failing to conform to the expected demands of either ‘love interest’ or ‘femme fatale’ archetypes.

It’s possible that the inclusion of these characters was simply the result of a compromise between the film’s producer(s) and writer / director, allowing ‘T-Men’ to include at least some kind of female interest without diluting the film’s procedural / quasi-documentary framework by resorting to rote romantic/domestic interludes - but whatever the case, they certainly make for an interesting addition to the drama, and allow the movie to play a lot better for modern audiences than it might have done as a 100% male affair.

Once the stentorian voiceovers and Treasury Dept bullshit is all out of the way meanwhile, the legit parts of John C. Higgins’ script (‘suggested from a story by’ ubiquitous Hollywood ideas-woman Virginia Kellogg) may not exactly sparkle with verbal wit, but they do at least include enough blunt, hardboiled shop-talk to keep me entertained. (“What’s the matter, ya gettin’ the whim-whams?”, a fellow hood asks O’Keefe when he seems reluctant to embark on a murder assignment.)

Brilliantly, the character played by Jack Overman (a distinctive actor with somewhat Asian features who also appeared in both ‘Brute Force’ and ‘Force of Evil’) answers to the name of “Horizontal”, whilst other rough coves on our identity parade of a cast list include “Moxie”, “Chops” and “Shiv Triano”. If you’re a fan of good ol’ Hollywood tough guy shtick in fact, you can count ‘T-Men’ as pretty essential viewing.

The real star of the show though is of course mid-century America’s foremost poet of men in dark hats walking down shabby hotel corridors, John Alton, whose distinctive work on ‘T-Men’ single-handedly elevates the film from a fairly routine caper to a true masterwork of noir visual style.

Working a few years later on ‘The Big Combo’ (which I reviewed here), Alton famously managed to create both an airport and an opera house out of little more than a few strategically placed spotlights, some smoke and a few bit of wood and corrugated iron. Here though, he and art director Edward C. Jewell seem to have had slightly more at their disposal (including the use of real locations), and the results are often little short of extraordinary.

Few of the era’s DPs were able to add a sense of routine tough guy business quite as well as Alton does here. Throughout the film, underlit faces loom out of the shadows like horror movies ghouls, framed by beams of rusted steel or rotten wood, whilst tormented victims of beatings sprawl gigantically in the foreground of low angled shots, as groups of sweaty, behatted goons artfully cram themselves within the 4:3 frame as if they were stuck in a lift with a single flashlight.

Meanwhile, authentic downtown alleyways, gas towers and waterfront loading zones are all picked out exquisitely by Alton’s minimal, high contrast lighting, allowing his trademark looming silhouettes and distorted shadows to lend perhaps an even greater degree of expressionistic angst to the film’s visuals than he managed to conjure up back on the sound stages.

In an inspired touch, the film’s conclusion takes place aboard what appears to be a decommissioned cargo ship from whence the bad guys handle the manufacture of their counterfeit dough, and the lighting Alton manages to apply to this vessel is, as you might imagine, pretty remarkable.

Transforming the deck into a chaotic cat’s cradle of light and shadow within which harried, hunched figures dart, weave and fall through the final few minutes of climatic action, Alton seems to directly mirror the overlapping layers of urban disorder seen earlier in the film, in a number of daytime shots taken through reflection-clogged shop windows. Perhaps T-Men’s most distinctive visual motif, this sense of unfathomable chaos presents a disturbing contrast to the resolutely linear tale offered up by the film’s script.

Though it would be a stretch to call it a superior, or even particularly inspired, example of the form, ‘T-Men’s best passages nonetheless capture the absolute essence of the proletarian gangster-noir aesthetic that would define many of the most powerful examples of Film Noir to emerge from Hollywood through the late ‘40s and early ‘50s.Certainly, the level of visual imagination on display in the film remains pretty astonishing. Both in purely technical terms and as a seamless fusion of the realist and fantastical strains of crime movie aesthetics, Alton’s work cements it as a key exemplar of the genre’s trademark atmospherics, irrespective of it’s sadly all-too-obvious drawbacks as a narrative movie entertainment.

---