The Virgin of the Seven Daggers:

Excursions into Fantasy

by Vernon Lee

(Penguin Red Classics, 2008 /

collection originally compiled in 1962)

I think this was from the remaindered bookshop in East Dulwich? Price sticker on the back says £3.

Vernon Lee was the pen name of writer and art historian Violet Paget (1856-1935), and funnily enough, a very strange hardback compiling some of her work was one of the first books I ever scanned and posted on this weblog, way back in 2010. The best part of a decade later, I’ve finally found time to read some more of her work, courtesy of this recent Penguin edition, reprinting a ‘60s anthology of a set of stories originally published between about 1890 and 1910, I believe.

A remarkable personage by any yardstick, Paget/Lee may have been ostensibly English, but she was born in Boulogne and spent the vast majority of her adult life on the continent, eventually settling in Florence. In addition to her fiction, she wrote extensively on European travel, history and culture, and in her day she was considered a leading authority on the Italian Renaissance, as well as an enthusiastic advocate of the Aesthetics movement pioneered by Walter Pater in the late 19th century.

All of this comes across very strongly indeed in her ghost stories, which – in stark contrast to the Anglican parochialism favoured by her near-contemporary M.R. James – are all set in Southern Europe (Italy, and sometimes Spain or Greece), and are chiefly notable for their dense and intoxicating tapestry of esoteric historical detail, blending references to art, architecture, music, geography, aristocratic lineage, religious traditions, local legends and sundry other oddities into such a rich, brooding atmosphere of quasi-fantastical grandeur that it is difficult for an ignoramus such as myself to ascertain where her reportage of authentic period detail ends and her imagination begins.

The opening tale, ‘Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady’, concerns the illegitimate son of one Prince Balthasar Maria of the Red Palace at Luna, who, after incurring the Prince’s disfavour, finds himself exiled to a remote outpost of the kingdom, where he falls victim to the charms of the same predatory female snake spirit who did a number on one of his illustrious ancestors. (Mixing a decadent, fantastical atmosphere with a sardonic sense of humour, this miniature masterpiece was originally published in an 1895 issue of the notorious Yellow Book.)

‘Amour Dure’ meanwhile concerns a highly-strung young Austrian scholar who, whilst undertaking historical research in a mountainous Italian town, develops an unhealthy obsession with a notorious, Lucretia Borgia-like femme fatale who features prominently in the area’s folklore, and – in classic Jamesian fashion – pays dearly for his temporally unsound ardour.

‘A Wicked Voice’ – in which a similarly self-absorbed young composer working in Venice becomes haunted by the voice of an 18th century singer credited with uncannily abilities – has a disturbingly unglued, dream-like feel to it, culminating in a set-piece that feels as if it could have been shot by Dario Argento or Pupi Avati.

Most memorable of all though is probably this collection’s title story, a Spanish number in which the notorious sinner and womaniser Don Juan Gusman del Pulgar, Count of Mirador, uses fiendish necromancy to gain access to a secret subterranean world concealed beneath a tower of the Alhambra at Grenada, there to take possession of the ‘Moorish Infanta’, a Princess Bride who has lain there through the centuries in unholy, magical slumber. It’s quite something.

Needless to say, Vernon Lee’s fiction remains unfairly overlooked, and ripe for rediscovery. Although she began publishing these stories some years before James, they nonetheless represent a series of head-spinning twists on the same basic formula, so, if you’re in search of something a bit different for your Christmas ghost stories this year, look no further.

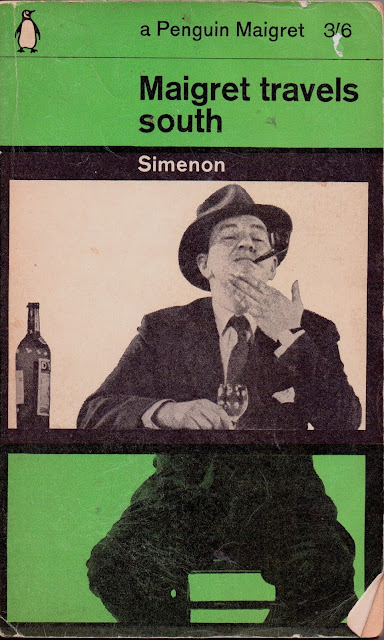

Maigret Travels South by Georges Simenon

(Penguin Crime, 1963 /

originally published 1940)

No idea where this one came from. All those Penguin crime purchases blur into one, especially the Maigrets. I’d buy ‘em by the kilogram if I could. (The cover shows Rupert Davies as Maigret, from the BBC TV series.)

For some reason, my favourite Maigrets always seem to be the ones that take him outside of Paris. With typical Simenon wit, this particular short novel sees the Chief Inspector “travelling south” in more ways than one as he arrives in Cannes to investigate the case of a dilettante Australian wool millionaire found stabbed to death on his own doorstep.

Routine sleuthing soon leads Maigret to the backroom of the ‘Liberty Bar’, a commercially redundant, essentially closed establishment where the food is good and the landlady accomodating, but where the air is also heavy, with a persistent atmosphere of fated, self-indulgent melancholy hanging over the handful of down at heel, demi-monde denizens who congregate there.

Like all of the best Simenon stories, this is one in which Maigret’s personal inclinations and human sympathies find themselves directly at odds with his obligations as a detective, and in which he thus finds himself weighed down by the guilt of knowing that his intrusion into the small, self-contained world of the story’s characters – so beautifully drawn by Simenon – has led, inevitably, to its destruction.

Though perhaps no great shakes as a mystery, these hundred-and-something pages pack a considerable emotional punch, knotting up some of the same bits of your insides as the best literary noir. Highly recommended.

MW by Osamu Tezuka

(Vertical Inc hardback, translated by Camillia Nieh, 2007 /

originally serialised in Biggu Komikku manga, 1976-78)

This was a birthday present – thank you Satori.

Osamu Tezuka (1928-89) exercised such a profound influence over the development of Japanese manga as we know it today that some subsequent fans and creators have gone so far as to treat him as an actual, literal God – a claim that begins to make a certain amount of sense when one considers both his staggeringly prolific work-rate and the consistently high quality of his precise, impactful artwork and conceptually innovative storytelling.

Although Tezuka remains best known in the West as the creator of the iconic Astro-Boy, and for his epic, multi-volume biography of the Buddha, his later years saw him expanding into darker, more adult-orientated territory, drawing somewhat on the Taisho-era Ero-Guro tradition of writers like Edogawa Rampo, but blending this influence with his own stark, modernist aesthetic, pushing the limits of his imagination in ever more extreme directions.

Sprawling across over 500 densely-packed pages, ‘MW’ arguably represents the culmination of this particular strain of Tezuka’s work, and describing its contents as “dark” feels woefully inadequate.

Though impossible to summarise in full, the story here centres on the intertwined fate of a grown man and a young boy who – for reasons too convoluted to go into here – find themselves spending the night in a cave on the coast of a remote island. Venturing out the following morning, they discover that the entire population of the island has been exterminated by what is later revealed to have been a deadly experimental nerve gas named MW, stored there by the American military.

Years later, the older man has become a Catholic priest, but he is still driven to tormented, soul-endangering distraction by his continued association with the young boy, who – after nearly dying from his exposure to MW on the island - has rather inconveniently grown up to become an androgynous, Fantomas-style super-criminal and master of disguise. Seemingly devoid of human empathy, as if his “soul” had been surgically removed, he commits all manner of terrible and perverse outrages, seemingly for no reason other than his own cruel enjoyment.

In the course of the story that follows, Tezuka pulls no punches in depicting a range of subject matter that takes in genocide, paedophilia, serial murder, rape, bestiality, torture and familial suicide, but does so with a sense of carefully honed, story-driven artistry that pushes the work way beyond the level of mere “transgressive” button-pushing.

Indeed, the obsessive precision of Tezuka’s artwork provides an unsettling contrast to the outrageous, frequently melodramatic, nature of the events he depicts, adding a genuinely psychopathic edge to proceedings that leaves the author’s actual intentions feeling strangely ambiguous.

Should we read ‘MW’ as a meditation on Catholic guilt and the essential nature of evil, or as a bitter commentary (both allegorical and literal) on the malign effects of America’s post-war dominance of Japan? Was Tezuka deliberately setting out to shock and appall his readers, perhaps using extreme imagery to detract attention from the tale’s uncomfortable political sub-text? Or was he simply concocting a vast ‘shaggy dog story’; a needlessly convoluted saga whose pleasures arise simply from the wickedly unlikely contrivances of its surface level story-telling..?

Somewhat inevitably, the best answer is probably “all of the above and much more besides”, but, whatever you end up taking from it, ‘MW’ remains a dangerous, multi-faceted hydra of words and pictures in which we see a master craftsman pushing the metaphorical envelope about as far as it can possibly go, making for an experience not easily forgotten.

UFO Drawings from the National Archives

by David Clarke

(Four Corners Irregulars hardback, 2017)

I bought this directly from Four Corners.

Between 1952 (when Winston Churchill demanded to know “..what all this flying saucer stuff amounts to”) and 2009 (when its operations were quietly shut down, having been deemed to have collected absolutely no useful intelligence whatsoever), The Ministry of Defense’s UFO Desk diligently collected and assessed untold thousands of reported UFO sightings across the British Isles.

Since 2007, when the desk’s files began to be declassified and incorporated into the National Archives, writer and academic David Clarke has been going through them with equal diligence, and as a result has compiled this attractive book, presenting a carefully curated selection of the drawings of alien spacecraft submitted to the MOD by members of the public during the years of the UFO desk’s operation.

As well as providing a wealth of rather splendid examples of quote-unquote ‘outsider art’, these drawings, accompanied by Clarke’s concise and non-judgemental summaries of circumstances surrounding their creation, provide an intriguing insight, not only into some very obscure corners of the 20th century British psyche, but also into what I have always considered to be the essential paradox underlying the UFO phenomenon.

Namely, the fact that, on the one hand, the vast majority of UFO reports are absolutely ludicrous - clearly beholden to the whims of popular culture and so completely lacking in plausibility, consistency or verifiable evidence that the possibility of their literal truth seems extremely unlikely.

But, on the other hand (and this in particular is highlighted by Clarke’s book), there is the fact that many of the people who make these reports do not seem to be the fantasists and attention-seekers that determined sceptics tend to assume, but quote-unquote ‘normal’, ‘sensible’ individuals with no prior interest in the subject, who in fact often seem embarrassed and upset by what they have witnessed, and beg the MOD not to publish their names or risk generating any publicity.

(Perhaps reflecting the demographic most likely to report their experiences directly to the government, a curious number of the witnesses featured in the book seem to have had a connection to the military or aerospace industries, and are apt to provide extremely detailed drawings of the craft they claim to have seen, complete with measurements and notes on construction materials, etc.)

Between these two impressions, something clearly doesn’t add up -- and it is this strange disjuncture which continues to fascinate, even as the fact that most first world citizens now essentially carry a HD video camera around in their pocket seems to have largely relegated UFOs to the status of a nostalgic, 20th century phenomenon.

Non-fiction-wise, I also read a great Pelican book about the history of Latin America this year, but I had to get rid of it because it had bookworm and was falling apart as I read it, so no review.