Saturday, 30 September 2017

October Horror Marathon:

Intro.

Intro.

As I have opined in these pages in past years, whenever October rolls around, as the nights draw in and we feel the chill in the air, I tend to find myself looking at other blogs and websites undertaking pre-Halloween marathons and “30 horror films in 30 days” challenges and suchlike, and feel a tinge of jealousy as a result of the fact that October is also a time of year in when I am usually really f-ing busy with a lot of tedious and draining, non-horror/Halloween-related things.

In all likelihood, this year will be no exception – indeed, obligations and flagged emails are already starting to pile up. But – this time, I’ve planned ahead. Despite the annoyances of sunshine and low-level frivolity, August and September actually proved pretty good months for mainlining horror movies, and thus I’ve managed to stockpile a stack of draft reviews to give myself a head start. So, whilst I’m not realistically going to be able to manage a post-per-day leading up to Halloween, I hope I will at least be able to average one horror movie review every two days through the coming month.

Given the time pressure under which they are being written, I can’t necessarily guarantee carefully polished prose, insightful observations and so on, but I will do my best. Expect about 75% first time viewings, leavened with reflections on a few old favourites, and perhaps even some documentaries, TV episodes, shorts and stuff thrown in for good measure. Mostly old/classic era stuff, but perhaps some newer bits and pieces too – we’ll see.

Well, whatever happens, I hope it will all help to get you in the mood for whatever depraved bacchanal festivities you have planned for All Hallows, and for an enjoyable winter of guttering candles, macabre tales and walks in the leaf-strewn cemetery more generally.

Posts beginning tomorrow, so stay tuned!

Nunhead Cemetery photograph credited to 'Martin Brewer', respectfully stolen from here.

Thursday, 21 September 2017

FRANCO FILES:

Los Blues de la Calle Pop

(1983)

Los Blues de la Calle Pop

(1983)

During my visit to Spain last year, prior to my pilgrimage to Calpe for the inaugural instalment in the (hopefully soon to be continued) Great Jess Franco Locations Tour, I was obliged to spend several days just down the coast in Benidorm – a town whose negative reputation couldn’t even begin to prepare me for the reality of its sheer, staggering awfulness.

A baking strip of wall-to-wall concrete and claustrophobic, decaying high rise hotels sucking the life out of a once idyllic beach front, Benidorm is populated largely by roving gangs of bloated, sun-burned British tourists, many of whom seem determined to live down to their nation’s very worst stereotypes by behaving in as thuggish and xenophobic a manner as they can get away with without attracting the attention of the town’s ever-present (and presumably long suffering) police patrols.

Along the front, bars seem to blast out Queen and Bryan Adams for about sixteen hours a day whilst serving microwaved pizzas and endless steins of watered down lager, whilst further back from the beach, the streets, distressingly, begin to resemble the dying centre of some economically deprived English town - full of familiar decaying chain stores, rubbish-strewn pavements and a vague sense of menace.

Deeper into what passes for Benidorm’s “pleasure quarter” meanwhile, in between Brit-owned faux-pubs proudly advertising the fact that no Spanish is spoken within, one can find beer-sodden strip joints, sex clubs and, I’m sure, vice-related enterprises of a less legal nature, all of an order so grimy and desperate that even Jess Franco himself might have thought twice before paying them a visit.

In view of these horrors, I have subsequently been delighted to discover ‘Los Blues de la Calle Pop’ (“The Blues of Pop Street”), an extremely strange little movie that Franco filmed in Benidorm in the midst of his early ‘80s Golden Films purple patch. (1) Herein, our hero rechristens the town “Shit City”, reimagining it in his own inimitable fashion as a kind of neo-noir dystopian wonderland of organised crime, rampaging punks and sweaty sexual violence.

Fitting roughly into the lineage of whimsical, ramshackle thrillers Franco had been occasionally banging out ever since La Muerte Silba un Blues in ’62, the inexplicably named ‘.. Calle Pop’ (wouldn’t “Shit City” have been a better title?) begins with a scene in which down at heel private eye Felipe Marlboro (Antonio Mayans) is hired by a sad-eyed young lady named “Mary Lucky” (played, with typical Franco weirdness, by a one-shot actress credited only as “Mary Sad”). She pleads poverty, but reluctantly agrees to pay Marlboro back with a bit of casual sex if he will travel to Shit City to locate her missing boyfriend, who goes by the name of “Macho Jim”.

Mary hands Mayans a picture of “Macho Jim”, and, in a rather bizarre visual gag, we see an insert shot of a Frank Frazetta-style barbarian illustration, prompting the observation that ol’ Jim certainly seems to live up to his name. Other shots of Frazetta artwork will proceed to pop up once or twice through the rest of the film, though whether they are intended as Godardian avant garde interjections or just weird attempts at humour, who knows.

Similarly, quite why the protagonist of this movie is named “Felipe Marlboro”, despite being essentially the same character as Franco’s frequently recurring private eye Al Periera, whom Mayans played on many occasions, is likely to remain a mystery for the ages.

In a further eccentric touch, stills of the Manhattan skyline are used to illustrate the opening credits sequence, over which the credits are scrawled in the form of blood-red children’s sprawl, accompanied by crude, stick-man illustrations, whilst a dusty old bossa-nova/fuzz-rock track blares in the background.

Arriving in ‘Shit City’, Marlboro of course has to stay at one of Benidorm’s very few actual cool-looking hotels (shot from high angle, its geometric outline briefly captures a touch of the sinister, futuristic vibe Franco brought to the ‘Grande-Motte’ complex in Lorna The Exorcist).

Whilst making himself at home, Felipe discovers that his neighbour in the hotel is some kind of loud-mouthed dominatrix type person who seems to have stepped straight out of Derek Jarman’s ‘Jubilee’, complete with hair like a poodle attacked with spray paint, studded leather jacket and a dog collar.

Though Marlboro declines her offer of casual sex, they still hang about together a bit, and as such, he subsequently finds himself in the hot seat when she is unceremoniously murdered by a gang of sadistic underworld heavies, catapulting our hero into a theoretically complex (but actually just boring and inconsequential) sub-‘Big Sleep’ style mystery with the elusive “Macho Jim” at its epicentre… or something.

(The movie’s primary antagonist, by the way, is an unhinged flamenco dancer who assaults his victims via aggressive dance moves, accompanied by snatches of canned music on the soundtrack and cries of “please, not the flamenco!”. Perhaps it’s a Spanish thing, I dunno, but speaking as a foreigner I must say I found this line of humour somewhat less than hysterical. Flamenco-guy’s main sidekick however is a moustached ‘70s long hair / aviator shades type dude, which I thought made for an amusing contrast.)

As I have stated in prior reviews, I feel that, to some extent, Jess Franco never really got the 1980s. Whilst he remained as prolific as ever through the first half of the decade, I just don’t think he was ever managed to exploit the aesthetic of the era as successfully as he had during the ‘60s and ‘70s - thus aligning himself with a long list of ‘60s veterans in all creative fields who hit the skids in a big way once 1980 rolled around.

But, this failure certainly wasn’t down to any lack of effort on Franco’s part, and, as my brief synopsis above implies, what we find ourselves looking at here is – brace yourselves – a Jess Franco movie full of punks.

Yes, the streets of Shit City are veritably overflowing with cockerel-haired, safety pin adorned, leather-clad miscreants, of whom the ill-fated dominatrix girl and “Macho Jim” (when he eventually makes an appearance) and but two, and indeed, Franco’s take on the punk sub-culture is just as off-beat as you might imagine.

Well, I say ‘off-beat’, but it’s really more just lazy, to be honest. The beliefs and tastes of the ‘punks’ are never addressed by the film, and basically it is easy to imagine that, when Franco found himself working on a story that featured a lot of ‘youth’ characters, he just asked “hey, uh, how are the kids dressing these days? It’s all this ‘punk’ thing, isn’t it?”, prompting whoever was responsible for the film’s make up and costumes gave him a big HELL YES and then go absolutely bananas with the idea.

Whoever was responsible, ‘Los Blues de la Calle Pop’s low rent urban warriors are certainly a sight to behold, verging on ‘Rollerblade’/‘Intrepidos Punks’ level ridiculousness at times. Much face paint is in evidence alongside the requisite overdose of hair-spray, whilst the female punks sport plastic-y looking chains and fragments of mismatched lingerie, whilst appearing to have taken a few lessons from the Betty Rubble school of DIY dress design.

My favourite male punk meanwhile is a guy who wears a black golf visor with “PUNK” written on it with correction fluid, combined with a homemade swastika patch, black leather driving gloves and a Phil Oakey-style face-covering forelock. I don’t know how much they paid him to walk around Benidorm dressed like this, but it wasn’t enough. (2)

Meanwhile however, there is not even the slightest hint of ‘new wave’ music to be found within ‘..Calle Pop’ – quite the contrary, in fact. Indeed, I’m sorry to report that most of the music used here is at best inappropriate, at worst singularly dreadful, consisting of a bunch of lumpen, cheesy big band jazz cues of the kind more traditionally used to enforce a ‘jaunty’ atmosphere in unspeakably Germanic sex comedies. (Hell, for all I know Franco might have picked up some tapes of this stuff whilst making an unspeakable German sex comedy.)

Wherever it originated from, this ‘wacky’ guff plays loudly and incessantly through much of the film, pretty much destroying any attempt to create a dystopian/neo-noir kind of ambience, and driving me to distraction in the process. (Seriously - it’s awful.)

We do at least get some brief respite from the trombone however when, in a delightful instance of only-in-a-Jess-Franco-film surrealism, it turns out that Shit City’s punk rockers like to congregate in a ‘piano bar’, where they listen intently as the director himself (playing a kind of loosely Film Noir inspired nightclub pianist/informer type character named “Jack Chesterfield”) lays down some gentle boogie-woogie and mellifluous lounge jazz for their delectation.

This being a Franco film of course, the ubiquitous punks are also dedicated strip club patrons, and it is here, needless to say, that we encounter Lina Romay – appearing in her ‘Candy Coster’ alter-ego – who essays the role of “Butterfly”, the latest in a long line of happy-go-lucky exotic dancers / sex workers portrayed by Romay in Franco’s films from the mid ‘70s through to the mid ‘80s.

Often, Lina’s nightclub scenes are highlights of the films in which they feature, with the couple’s unique voyeur/exhibitionist relationship firing on all cylinders (from my own reviews, Los Noche de los Sexos Abiertos, filmed the same year as this one, proves a pertinent example), but sadly, Franco’s mojo seems to have deserted him here, and the strip club routines are pretty dire.

Capturing Lina as she works her way through a listless, buttock-grinding routine that proves distinctly unflattering to her increasingly plump form, these typically lengthy digressions see her rolling around and gyrating rather clumsily on the grubby stage, basically resembling the kind of unedifying spectacle one might expect to see in an actual Benidorm strip club. Rendered even less enjoyable by the fact that she seems to be moving to a completely different beat from the mind-numbing easy listening cue heard in the finished film, I’m afraid this is definitely not a highlight of Ms Romay’s storied career in erotic cinema.

Actually, it is interesting to note that, for the most part, ‘Los Blues de la Calle Pop’ is entirely lacking in the kind of sexual content one would expect of an ‘80s Franco film. Though the storyline itself is full of unseemly business (prostitution, strip clubs, sexualised murders), someone involved in the production seems perhaps to have taken a last minute decision to pitch the film at a slightly different audience, and as such, nudity and on-screen sex is kept to a minimum (by Franco standards, at least). Despite being staggeringly sleazy in most other respects, the aforementioned nightclub scenes for instance don’t even see Lina taking her g-string off (which perhaps to some extent explains why both she and Jess seem so bored with the whole affair).

But then, late in the movie, Franco goes and blows the whole deal with a lengthy Mayans/Romay love scene, filmed as was often his want in this era entirely via near-abstract close-ups, including the sight of Mayans spending a great length of time sticking his chops into what I’m *fairly sure* must be an artificial bush (though with Lina, I wouldn’t count on it). Maybe they thought the censors wouldn’t mind if it was a fake one, or something? Who knows.

In light of this confused approach, it is difficult to figure out quite who this film was supposed to be aimed at, or indeed how it secured a release at all, given its DIY level production values and lack of any easily exploitable content. (3) As with most of Franco’s straight ‘thrillers’, casual viewers are liable to find ‘..Calle Pop’ an off-putting, meandering and generally infuriating experience, whilst its intentional comedy elements alternate between the hopelessly clumsy and the simply incomprehensible. The “youth movie” aspects that the film’s domestic VHS release gamely tried to play up meanwhile never really materialise, with the generally sleazy vibe further mitigating against this idea, so, without any real erotic material to fall back on, what does that leave us, beyond a barely releasable load of lackadaisical, in-jokey Franco hoo-hah?

Well, for dyed-in-the-wool Franco freaks such as myself of course, such barely releasable hoo-hah is very much our bread and butter, and in spite of everything, ‘Los Blues de la Calle Pop’ is actually a surprisingly engaging film on a purely visual level. As I discovered when returning to it to take some screenshots for this review, if you play it through with no sound or subtitles, it actually starts to look like pretty great in places.

Some scenes utilise rich, deliberate colour schemes (red walls and stained glass), picked out with what looks like it might have been quite decent cinematography before the ravages of VHS took hold. At various points in the film, different varieties of red filters are even used – sometimes to create an atmospheric ‘evening’ effect, and sometimes just for the sake of random weirdness (such as making a drab hotel lobby look like a photographic dark room).

In another characteristic Franco touch, ‘accidental’ camera blunders (over-saturated sunlight, lens flare, botched focus etc) are actively encouraged, and indeed exaggerated in the name of added visual interest. In particular, rainbow-coloured light halos, created by strong light sources shone directly into the camera, can be seen exploding all over the place like cost-free psychedelic effects.

At the other end of the technical spectrum meanwhile, a brief scene in Lina’s dressing room casually pulls off a nifty ‘infinite mirror’ effect, and a red-tinted final confrontation between the two leads is constructed with great skill and no small amount of style, paying effective tribute to the jagged framing and editing patterns of classic Film Noir. The film’s editing (credited to David Raposo) is actually very good throughout, meaning that, mystifyingly awful though it may be in many ways, ‘..Calle Pop’ at least never drags. (4)

Franco’s usual ADHD tendencies also see him splicing in static close-ups all kinds of posters and decorations adorning the bars and apartments in which the film is shot, some of which – including the Frazetta illustrations referenced above and a Victorian print of a train accident assigned the English caption “Oh Shit!” - seem to provide oblique commentary on the on-screen action. Between shots of Bogart, Marilyn, Led Zeppelin and Adam & The Ants, the cultural iconography of Benidorm circa 1983 is certainly well-explored here.

Locations are used reasonably well (I was particularly delighted to see an early ambush/fight sequence staged within the monolithic shopping mall that I ventured into to pick up some breakfast supplies during my stay), and the idea of reimagining Benidorm as a kind of floating, pulp fictional dystopia is an absolutely brilliant one, although sadly Franco doesn’t seem to have put a huge amount of effort into realising it on screen.

As usual in these Al Periera-type movies, he seems to have been more concerned with goofing on a few half-remembered scenes from whatever classic Hollywood crime movies were on his mind at the time, and, as usual, one suspects this was a lot more fun for the director than it is for his audience.

For first time in fact, we get a definite sense in ‘..Calle Pop’ of Franco getting old. Up to the mid-70s at least, his films felt at least somewhat in tune with the zeitgeist, comfortable in their own skin you might say, but here he demonstrates little interest in the contemporary characters and settings, instead subjecting his viewers to the squarest music imaginable whilst giving every indication of wishing to return to the glory days of his youth, taking in some black & white studio masterpiece in a darkened Madrid picture house.

One gets the feeling here that by this stage in his career Franco really just wanted to make his own ‘Kiss of Death’ or ‘The Big Combo’ or something… but, when you find yourself in Benidorm in 1983 with a few Pesetas in yr pocket and a cast & crew consisting mainly of local kids, you’ve got to adjust to your circumstances, and ‘..Calle Pop’ is the somewhat confused result – a massively self-indulgent work, complete with an overriding tone of camp self-awareness that would go on to shape the majority of the director’s dreaded post-1990 Shot-On-Video output.

For its sheer strangeness, for the chance to see Franco’s take on Benidorm, and for all the random, piano bar-frequenting punks, I confess I actually quite enjoyed ‘Le Blues de Calle Pop’ on its own terms, but at the same time, it is not a viewing experience I would necessarily recommend to many other human being. As should be abundantly clear by this point, we’re well into a “For Madmen Only” corner of Franco’s filmography here, so if you’re anything less than a tenth level adept of the great man’s canon, I’d advise approaching with caution.

…

(1) Despite being shot during the period in which Franco was primarily working for Golden Films, ‘..Calle Pop’ seems to have been shot without their intervention, with the credits assigning the production solely to Franco’s own Manacoa Films. Combine this with the lack of any credited producer and ‘..Calle Pop’s bottomless eccentricity, lack of easily exploitable genre elements and general obscurity all come into sharper focus.

(2)In tracking down and watching ‘Los Blues de la Calle Pop’, I have actually found myself fulfilling my long-standing ambition of discovering a film crawling with punks which was NOT included in Zack Carlson & Bryan Connolly’s otherwise encyclopaedic Destroy All Movies: The Complete Guide to Punks on Film. I wish I could take the opportunity to become probably about the 78th person to point out this oversight to the authors, but the book’s promotional website is long-dead by this stage, and it was out of print the last time I checked, so what can ya do?

(3)According to IMDB’s always eerily hyper-specific box office data, ‘Los Blues de la Calle Pop’ did actually enjoy a brief theatrical run in Spain, selling exactly 5,401 tickets and earning 1,291,425 Spanish Pesetas.

(4) An editorial assistant on a number of mainstream/arthouse films in Spain during the ‘70s (as well as the 1975 Exorcism knock-off “The Devil’s Exorcist” with Jack Taylor), Raposo seems to have moved toward (s)exploitation fare when he took on full ‘editor’ status in the early’80s, although I believe this film is his only credit for Franco.

Saturday, 16 September 2017

Deathblog:

Harry Dean Stanton

(1926-2017)

Harry Dean Stanton

(1926-2017)

Well, so long Harry Dean.

What can we say about the man that hasn’t exhaustively been said elsewhere, or that isn’t immediately made obvious through watching him on screen?

The cult bit-part actor who was so great at being a cult bit-part actor that he blew the whole deal and hit the mainstream, becoming a universally beloved icon of.. whatever it is the mainstream ain’t got; the taciturn barometer of realness in the black heart of Hollywood fakery; the inscrutable zen cowboy sensei; the living embodiment of that old chestnut about there being “no small parts, only small actors”; the kind of guy who could fill you with a dozen different mixed up feelings just by walking on-screen, looking straight to camera and saying a few words; the face of a man who could stare down to collective weight of all the world’s bullshit and tell it where to get off, before returning to whatever he was doing before it interrupted him… and probably did so on a regular basis for all we know.

At some time, to some people, he was all those things, but around here we’ll remember him above all for his immortal performance in ‘Repo Man’, providing the perfect ersatz father figure for the punk generation.

The last time I checked, there were something in the region of about 11,000 different things I like about ‘Repo Man’, but high on the list following my most recent viewings is the unspoken realisation that seems to overcome Otto when he falls under Bud’s tutelage: man, there’s nothing new about any of my shit AT ALL.

I could do all the quotes, but… you know ‘em, I’m sure. If you don’t, learn ‘em. For that role alone, he was one of the greats, but beyond that, I for one am sad that the potential total number of those “fuck yeah, it’s Harry Dean Stanton” moments discerning viewers of American films live for has now been capped forever.

R.I.P. H.D.S.

Sunday, 10 September 2017

Old New Worlds:

September 1965.

September 1965.

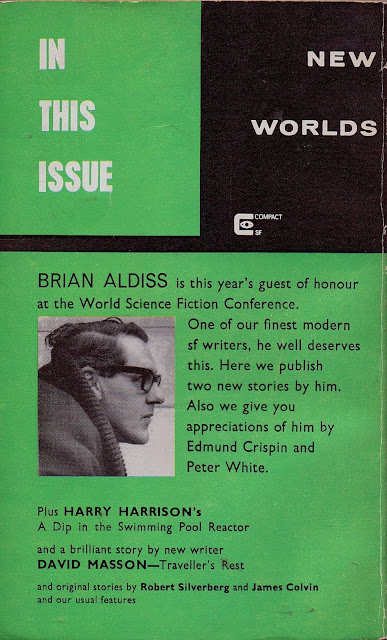

To further mark the recent passing of Brian Aldiss, I thought it might be a good idea to revive my long-neglected ‘Old New Worlds’ thread [click on the ‘New Worlds’ tag below to view earlier posts] to cover the issue that was once, long ago, lined up as the next instalment – an issue that, as luck would have it, is almost entirely dedicated to Aldiss and his work.

At this point in time, New Worlds had largely dispensed with interior illustrations, meaning that this issue contains relatively little scan-worthy material, but we do at least have the wonderfully bizarre, unaccredited cover illustration (is it a photo, some kind of collage..?), whose distorted, sensuous landscape seems a clear reflection of editor Michael Moorcock’s campaign to gradually move the magazine’s aesthetic reach beyond the confines of the stylised spaceships and meteorites that were gracing its covers just a few months earlier.

This seems to lead neatly into a short ‘appreciation’ of Aldiss by Edmund Crispin, which kicks off issue # 154.* Crispin here crowns Aldiss “The Image Maker”, drawing an interesting distinction between science-fiction (which “..can be good even when its visualisation – of a Martian, a metropolis, a mutant – is relatively sketchy and commonplace”) and science-fantasy (in which “..the quality of the visualisation is the all-important thing”), and crediting Aldiss as one the most gifted proponents of the latter strain, despite his embrace of the surface trappings of the former. “Aldiss has a painter’s eye”, Crispin concludes. “Compared with him, almost all other sf writers (take the ‘f’ whichever way you like) work in black and white.”

In his editorial meanwhile, Moorcock gets a little more personal in his praise;

“Apart from being admired for his talent, Brian Aldiss is also amongst the most well-liked of sf writers; charming, ebullient, fluent, not unhandsome, a gourmet and man of good taste and humour, he is as interesting to meet as he is to read. His criticism, in The Oxford Mail and SF Horizons, is intelligent and pithy, matched only by a few.”

If that weren’t enough, we even get a third, quite lengthy, appreciation of Aldiss’s work, from Peter White, who muses;

“However much he may attack the priggish inhumanity of bureaucrats, moralists, and politicians, and suggest that we should take life as it comes, he always deals with sadness more vividly than joy, and his very choice of subjects is mournful. Many of his heroes […] are intelligent plebeians; too repressed to be earthy, and without the well-bred grace to be aristocratic. Filled with a vague sense of loss, they search for a better life. Nearly every one of his major novels takes the form of a quest without any real conclusion. Perhaps it is this that makes his writing seem so valid to the world now, where the bright lights, dark and crowded dance halls, high-speed along the bypass, casual sex and beat music, all seem like drugs to keep us going until we can get hold of something real.”

White also sees fit to note that Aldiss was born in Norfolk “within a stones throw of F.L. Fanthrope” (no prizes for guessing in which direction he might have preferred the stones to be thrown).

For all these fine words though, perhaps the most pertinent summation of Aldiss’s approach to life in this issue comes from the man himself, who is quoted by White as follows;

“I wish to continue to write as I want, and to be published, and to earn a reasonable income, and perhaps in this way to make a contribution to the rich and wonderful culture into which I was born and which, despite all its horrors, never ceases to delight me day by day.”

Gifted as we now are with the knowledge that that is indeed what he continued to do for over fifty further years, I feel this is as good an epitaph as any for what I am certain was a life well spent. R.I.P. Brian.

Elsewhere in this issue’s non-fiction pages, ‘James Colvin’ (previously unmasked in these posts as a beard for editor Moorcock himself [note the initials]) waxes lyrical on the qualities of J.G. Ballard’s recently published ‘The Drought’:

“It is an intellectual and visionary novel of marvelously sustained power and conviction, […] reminding one constantly of the burning landscapes of the best surrealist painters. Its approach to Time and Space produces a sense of the ultimate merging of physics and metaphysics in that intensely individual way of Ballard’s, where grotesque, tormented characters inhabit and reflect a bright nightmare world that is at once unreal and yet real in the sense that it totally convinces on the level of the unconscious, cutting past the defenses of the outer mind and reaching the core of the inner mind, evoking responses that the reader did not know he had and, perhaps, does not understand even as he experiences them.”

Significantly, the talented Mr. Colvin pops up again elsewhere in #154 with what perhaps could be interpreted as one of his own humble attempts to evoke similar responses in his readers - a sixteen page story named ‘The Pleasure Garden of Felipe Sagittarius’.

Described in Moorcock’s editorial as “an experimental story of a kind [Colvin] believes hasn’t been tried before and which, he says, is ‘meant to be enjoyed, not studied’”, this story actually turned out to be an extremely important turning point in Moorcock’s writing.

Beginning with the image of ‘Minos Aquilinas’, “the top Metatemporal Investigator in Europe” clambering through the war-torn ruins of an alternate-world Berlin, the story posits that murder has been committed in the unnaturally verdant garden of the city’s police chief, Otto Van Bismarck, and that Bismarck’s personal assistant, one Adolf Hitler, is up to his neck in suspicion.

Also factoring in appearances by Kurt Weill, Albert Einstein and Eva Braun, and presenting the titular Felipe Sagittarius as a cultivator of lethally hallucinogenic, erotically scented greenery, this extremely strange first person detective story may be sketchy in the extreme, but it nonetheless introduces us – possibly for the first time – to the kind of temporally/spacially unmoored dystopian vignettes that would go on to define the style of the Jerry Cornelius mythos that Moorcock unleashed a few years later, as well as prefiguring the pungent aesthetic decadence that would characterise his experimental fiction as a whole, and even hinting at the kind of perverse alternative history scenarios that would increasingly predominate in his work through the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Clearly recognising the story as a bit of a ‘skeleton key’ work in this respect, Moorcock later revised it (under his own name, natch) when he came to compile his series of “Eternal Champion” compendiums in the early 1990s, re-christening the protagonist as a member of his Von Bek dynasty and placing it in the very first volume of the series, alongside several much later novels.

Confusingly, there was also a third iteration of the story at some point, this time with the narrator identified as “Simon Begg”, but, leaving such delving into the labyrinths of Moorcock’s literary revisionism aside for now, it is certainly a thrill to see ‘The Pleasure Garden..’ appearing for the first time here, hot off the presses and straight from the young editor’s fevered brain.

*A gentleman of of widely varied talents, Edmund Crispin is probably best-known for his series of ribald comedy-mystery novels, including ‘The Moving Toyshop’ and ‘Unholy Orders’, which I can highly recommend. Wikipedia also informs me that he wrote the score for The Brides of Fu Manchu, of all things, as part of an extensive composing career under his birth name Bruce Montgomery.

Monday, 4 September 2017

Deathblog:

Brian Aldiss

(1925 – 2017)

Brian Aldiss

(1925 – 2017)

This is a somewhat belated Deathblog I’m afraid, but I actually recently learned of the death of Brian Aldiss, who passed away last month, one day after his 92nd birthday.

Although I don’t currently know enough about Aldiss’s personality, private life or beliefs to discuss him on that level, or to really miss his presence on earth in an emotional sense, I have nonetheless been in the process of familiarising myself with his core science fiction novels over the past couple of years, and have been enjoying them immensely.

Of course, ‘Frankenstein Unbound’ (1973) was always one of my favourite time/reality-bending ‘headfuck’ novels from back in my teenage years, and I’ve always enjoyed Aldiss’s short stories here and there, but, more recently, I’ve caught up with ‘Non-Stop’ (1958), ‘Hothouse’ (1962) and ‘Greybeard’ (1964), and can recommend all three in the highest possible terms; in fact I think you’d be hard-pressed to find as excellent a trio of SF books completed by any author within a five year period. Needless to say, I have a small pile of other Aldiss’s lined up to read in the near future, beginning with 1969’s presumably somewhat psychedelically-inclined ‘Barefoot in the Head’.

Though Aldiss never really crossed over into mainstream success or cult legend in the manner of Dick, Ballard, Kneale or Moorcock, his combination of wildly unhinged imagination, rich aesthetic vision and genuine literary chops increasingly make me feel that he really deserved to.

Frankly, I can only assume it was only the highly varied and profligate nature of his output – combined perhaps with the square/low key nature of his public persona – that keeps him confined to the dusty hearts of the hardcore SF crowd, rather than filtering through to Penguin Classics lists, student bookshelves and conferences about what it means to be “Aldiss-esque”.

Seemingly a veritable writing machine throughout his life, Aldiss’s work also encompasses vast quantities of literary fiction, criticism, essays, auto-biography and miscellaneous non-fiction, not to mention his successful trilogy of saucy, quasi-autobiographical ‘Horatio Biggs’ novels – all of which I am, again, not currently well placed to comment upon, but I can at least point you in the direction of Christopher Priest’s excellent obituary for The Guardian to fill in the gaps.

For the lack of anything else to add, I’ll simply treat you to a quick gallery of various Aldiss paperbacks that I currently have scattered around my shelves. They’re not necessarily always the most attractive designs that graced his books (although I love the Four-Square ‘Earthworks’ cover), and they’re definitely not in the best condition for the most part, but I hope they might at least give newcomers a feel for the breadth of his SF writing and the challenges it posed to cover designers.

(Dates given below are for the edition pictured, not the dates of original publication. Cover artists are all unknown/unaccredited, sadly.)

(1967)

(1974)

(1976)

(1965)

(1968)

(1982)

Labels:

books,

Brian Aldiss,

British culture,

deathblog,

science fiction,

writers

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)