Sunday, 30 July 2017

Ritual # 1.

Segueing neatly from last week’s post into a bit of shameless self-promotion, this seems a fitting moment to alert you to the fact that I actually utilised the previously quoted passage from ‘Satan’s Slaves’ as part of the text accompanying a new musical [or, perhaps I should just say, “sound”] venture that I threw online a couple of months ago.

In essence, Count Dracula’s Great Love aims to combine sounds from the past with some recorded in the present, mixing and manipulating the two in an attempt to conjure and explore the mysteries, aesthetics and atmospheric resonances of particular times and places long gone. Realised at least partially via the means of a trusty VHS player, assorted boxes with knobs on and a digital four-track, the project’s initial instalment mines the darker side of the American South-West in the early 1970s, and can be sampled either via the link above or through the embedded box below. If you dig it, or get something out of it, please spread the word.

Tuesday, 25 July 2017

Bloody NEL:

Satan's Slaves and the Bizarre

Underground Cults of California

by James Taylor

(1970)

Satan's Slaves and the Bizarre

Underground Cults of California

by James Taylor

(1970)

"It happens. It has happened. It will happen again. The West has its spaces -- wide-open spaces. The fuzz can't be everywhere. The nearest police station could be a hundred miles away. A fire only shows for a few miles. Sound only travels a short distance before erasing itself in the atmosphere. […] Across the canyon, in the other hills, another group played out the last rites of a witchcraft ceremony -- and the orgy prepared to cut loose."

- p. 126

Following on from the Manson-ite speculations contained in my review of The Dunwich Horror earlier this month, not to mention the recent announcement that Quentin Tarantino intends to make a new Charles Manson movie (reaching cinemas in time for that all important 50th anniversary, no doubt), this feels like as good a moment as any to pull this one off the shelf and give it a quick once over.

New English Library hold a well-deserved reputation as the sleaziest of UK paperback imprints, but even so, they really outdid themselves here with an example of pulp non-fiction at it’s most crassly exploitative, complete with an unaccredited publicity shot of the recently murdered Sharon Tate gracing the back cover.

Predictably enough, searching online for info pertaining to one ‘James Taylor’ who “tried to found his own religion” in “the ‘golden land’ of California” yields little, but regardless, we can assume that the whole ‘religion’ thing didn’t work out too well for the mysterious Mr Taylor, as the early months of 1970 seem to have found him taking a deep breath and banging out no less than 127 pages of prose for NEL, armed with nothing more than a few newspaper articles, a passable command of contemporary hipster patter and a vague memory of watching some horror movies.

As a result, I think we can safely claim that ‘Satan’s Slaves’ was one of the first (if not THE first) “Manson books” to hit shelves anywhere in the world – an achievement only slightly undermined by the fact that it is utter bollocks.

That’s not to say of course that it is anything less than a wholly enjoyable read for those of us inclined to read such a thing in the first place. Writing in a free-flowing, gonzo style that allows him to leave narrative strands hanging whenever he feels like it and switch subjects on a dime, Taylor initially sets out his stall with a bunch of vague “L.A. – city of evil” / Hollywood Babylon type think-piece blather, before giving a general “overview for the squares” of the expansion of California’s 1960s counter-culture from it’s Beat Generation origins through to the glory days of Haight/Sunset decadence.

Taylor then moves on to a few case histories of earlier L.A.-based religious hucksters (Father Riker, L. Ron Hubbard, Sister Aimee McPherson), all related with the “insider gossip” curled lip sneer of a mid-century tabloid expose. Adding to the general tabloid vibe, the author also throws in some great, entirely arbitrary, chapter headings like ‘NO HALO FOR SATAN’ and ‘INTERCULTIC BATTLEGROUND’, which I enjoyed. He also goes into great detail concerning the careers of certain cult leaders and religious organisations (eg, the ‘Bakar Ifna Temple’, ‘Charles Irish’) whose activities remain so thoroughly underground that a google search turns up nothing except references to this book.

More parochially, the supposedly California-dwelling Taylor also finds time to criticise the ‘blundering’ attitude of Britain’s Labour government in reforming the trade unions, and complains that the MBEs awarded to The Beatles are “little short of bribery”, for some reason.

Charles Manson himself fades in and out of the book’s digressive flow, with the paucity of concrete info available to Taylor at the time of writing sometimes becoming painfully clear. [Although the month of this book’s publication in 1970 is unknown to me, the author mentions several times that a date for the Family’s forthcoming trial – which began in June of that year – had not been set whilst he was writing.]

Interestingly, Taylor does reference the alleged connection between Manson and The Process Church of the Final Judgement, demonstrating that this idea (now a ubiquitous part of the mythos surrounding Manson) was already common currency even this early in the game. He also speculates, apropos of nothing, that Manson might have picked up some of his mystical hoo-doo by “meeting a Scientologist in prison”, so… there ya go.

Happily, when rehashing the available press cuttings starts to run thin, Taylor wisely decides to take off into the realms of pure fantasy, penning a number of lengthy, entirely fictional fantasias of Death Valley orgies and Satanic invocations whose blood-curdling content could have fitted right into some post-Manson hippie horror movie of the ‘Werewolves on Wheels’ / ‘I Drink Your Blood’ variety. At some point in proceedings, the author even seems to drift into an assumption that Manson and his followers were actual, card-carrying Satanists (see caption on the photo above), and he also alleges that Manson personally ordered the slayings of at least twenty five people in the Los Angeles area.

Needless to say, if you dig the particular aesthetic of this cultural moment, and if the extreme bad taste of the whole venture doesn’t put you off, ‘Satan’s Slave’ proves an absolute hoot, best enjoyed as a piece of somewhat factually-influenced pulp fiction.

[UPDATE: according to this paragraph in Tony Allen’s ‘Brit Pulp! The Fast and Furious Stories from the Literary Underground’ (Sceptre / 1999), ‘Satan’s Slaves’ was actually the work of frequently pseudonymous NEL scribe James Moffat, best-known for writing the ‘Skinhead’ series and various other young adult books under the name ‘Richard Allen’.]

Labels:

1970s,

books,

California,

Charles Manson,

cults,

hippies,

James Moffat,

L.A.,

New English Library,

non-fiction,

Satan,

strange goings on,

true crime

Monday, 17 July 2017

Deathblog:

George A. Romero

(1940 – 2017)

George A. Romero

(1940 – 2017)

Like most people reading this I’m sure, I was saddened to wake up this Monday morning to the news that George Romero has passed away.

Turning on the radio whilst I made my breakfast, I was slightly taken aback to hear, of all things, Ed Harris enthusiastically reminiscing about working with Romero on ‘Knightriders’ in 1981 – and, a few seconds later, the penny dropped. Receiving the news via the gracious and heart-felt recollections of Mr. Harris was surely a hell of a lot better than catching Radio 4’s presenters delivering some sardonic, and-in-other-news bit about “the man who invented zombies” or somesuch, so – thanks for that Ed, I appreciate it, and thanks too to whoever at the BBC decided to give him a call.

A death like this represents a lot of stuff to unpack, not only for horror fans, but – I would like to stress – for anyone who gives a hoot about independently minded American cinema in general. I don’t have anything like the time or means to embark on a full scale obit today (hopefully we can return for some follow ups later), but let’s start out on a personal level and see where this goes.

I was a pretty late comer to horror movies – through my teenage years I was far more devoted to science fiction and quote-unquote “serious cinema” – but when I did begin to become fascinated by the genre, Romero was my way in. Probably this was because, whilst the majority of his films are IN the genre, they rarely seemed OF the genre, if you get what I mean.

His voice, his sensibility, his ideas, all seemed to come from somewhere else - Pittsburgh, specifically, although I didn’t really have a grasp of this at the time. He was clearly coming from somewhere outside of the ‘industry’ anyway, somewhere outside of the cultural and market trends that, though he may have helped shape them from time to time, he never followed if he could help it.

‘Night of the Living Dead’ (recorded off the TV) was one of a very small handful of movies I would obsessively watch over and over again through the years on either side of my twentieth birthday. There’s probably not much I can say about it that hasn’t been (exhaustively) said before, but something about it (the sheer, uncompromising, punk-spirited grimness of the whole venture and it’s refusal to collapse into camp despite the cheap/pulpy context, I suspect) kept me coming back for another dose, and, though I perhaps would no longer deem it The Best Horror Movie Ever as I did in 2011, to this day it remains one of those films I could watch pretty much every day without getting tired of it.

Inevitably, ‘Dawn..’ and ‘Day..’ (both also recorded off TV) followed, then ‘Martin’ and ‘The Crazies’ (bought second hand on Redemption VHS). All of these were – and are – fucking brilliant, and by this stage in my descent into cinema fandom, Romero was The Man as far as I was concerned.

In my mind, I built him up as a truly heroic figure, and never tired of telling people how great I thought he was. Conspicuously ignoring some of the more errant entries in his filmography, I saw him as the guy who never put a foot wrong – this bad-ass auteur who systematically rejected Hollywood bullshit, but wasn’t some pretentious arthouse type either. An underappreciated genius who had to fight to make his films, and who only ever rolled camera when he was sure he could do so on his own terms, with his own people – that’s how I saw it. Mighty George Romero, shakin’ the world once or twice a decade with works that were intelligent, imaginative, exciting, fast moving, socially conscious, harrowing, anti-authoritarian and authentically (though not gratuitously) violent. He made movies that treated their audience with respect, and didn’t let them down. A filmmaker of the people! A Cassevetes of the grindhouse!

And, as far as the selected canon of films I’ve referenced above is concerned, I think such hyperbole is still entirely justified, to be honest. But, had I dug deeper and come up with some of the maestro’s, uh, let’s say, slightly more questionable projects (‘There’s Always Vanilla’, ‘Two Evil Eyes’, ‘The Dark Half’, etc.), my enthusiasm might have been more sensibly tempered for his 21st century comeback.

As it was though, my anticipation when ‘Land of The Dead’ was announced was into the stratosphere. I had faith. And so, needless to say, I was pretty devastated when finally I saw the damn thing.

I know ‘Land..’ has gained some degree of retrospective appreciation within horror circles since its release, but at the time I hated every single thing about it, and have never had the stomach to revisit it. That The Great George A. Romero could take probably one of the biggest budgets he’d ever been accorded and return with a bunch of crap that resembled one of the dumb direct-to-video flicks I’d rent to kill time in the late ‘90s was a disappointment I just couldn’t even comprehend.

Today of all days though, we should probably draw a veil over the past few decades of creative frustration and disappointment, and just reflect that, hey, how many great independent/genre filmmakers *didn’t* hit similar brick walls after the year 2000? (I’m no industry insider, but suffice to say, I don’t think it was mere personal failings that similtaneously stopped the wheels rolling for Carpenter, for Argento, for Lynch, Franco, Hooper, Don Coscerelli, Ken Russell… and so the list goes on.)

Nowadays, I hope I have managed to attain a somewhat more nuanced take on Romero’s legacy, and am happier to embrace the strange and sometimes misguided places that his idiosyncratic approach to filmmaking took him in-between his aforementioned ‘hits’.

Looking over Romero’s filmography today, by my count he directed seventeen films, of which *seven* could conceivably be termed masterpieces – a hit rate not many Hollywood directors could compete with, and an especially remarkable achievement given the marginal/cash-strapped circumstances under which he usually worked.

Thus far unmentioned amongst those golden seven, I have of course come to love 1982’s ‘Creepshow’ as a wonderful Friday night horror flick, a total 180 from the stark realism of his other horror films and one of the best ever attempts to transfer a comic book aesthetic to film, but the one I keep coming back to, and that I immediately wanted to watch again upon hearing the news today, is ‘Knightriders’ – one of the most ambitious, and undoubtedly the most personal, project on Romero’s CV, and arguably his defining statement as a director, from a purely auteurist standpoint.

It is, admittedly, a hugely indulgent, over-long, melodramatic, shamelessly self-mythologising piece of work – but when it comes to a director like Romero, I’m willing to indulge. As a two hour plus tribute to the kind of independent creative spirit in which he believed, and to the extended filmmaking family in Pittsburgh who helped him realise his vision, ‘Knightriders’ is a uniquely moving film. The celluloid equivalent of a ragged victory banner waving in the breeze, it was doomed to commercial failure from its very inception, and is all the better for it.

In fact, I would go as far as to say that, if you’re thinking of paying tribute to Romero by watching some of his films this week, perhaps put the zombies to one side for five minutes and instead cue up‘Knightriders’ for a broader appreciation of the man whose voice and vision American cinema has lost this week. (And when ol’ Ed Harris returns to claim his crown at the end, there won’t be a dry eye in the house, I’m telling you.)

R.I.P.

Turning on the radio whilst I made my breakfast, I was slightly taken aback to hear, of all things, Ed Harris enthusiastically reminiscing about working with Romero on ‘Knightriders’ in 1981 – and, a few seconds later, the penny dropped. Receiving the news via the gracious and heart-felt recollections of Mr. Harris was surely a hell of a lot better than catching Radio 4’s presenters delivering some sardonic, and-in-other-news bit about “the man who invented zombies” or somesuch, so – thanks for that Ed, I appreciate it, and thanks too to whoever at the BBC decided to give him a call.

A death like this represents a lot of stuff to unpack, not only for horror fans, but – I would like to stress – for anyone who gives a hoot about independently minded American cinema in general. I don’t have anything like the time or means to embark on a full scale obit today (hopefully we can return for some follow ups later), but let’s start out on a personal level and see where this goes.

I was a pretty late comer to horror movies – through my teenage years I was far more devoted to science fiction and quote-unquote “serious cinema” – but when I did begin to become fascinated by the genre, Romero was my way in. Probably this was because, whilst the majority of his films are IN the genre, they rarely seemed OF the genre, if you get what I mean.

His voice, his sensibility, his ideas, all seemed to come from somewhere else - Pittsburgh, specifically, although I didn’t really have a grasp of this at the time. He was clearly coming from somewhere outside of the ‘industry’ anyway, somewhere outside of the cultural and market trends that, though he may have helped shape them from time to time, he never followed if he could help it.

‘Night of the Living Dead’ (recorded off the TV) was one of a very small handful of movies I would obsessively watch over and over again through the years on either side of my twentieth birthday. There’s probably not much I can say about it that hasn’t been (exhaustively) said before, but something about it (the sheer, uncompromising, punk-spirited grimness of the whole venture and it’s refusal to collapse into camp despite the cheap/pulpy context, I suspect) kept me coming back for another dose, and, though I perhaps would no longer deem it The Best Horror Movie Ever as I did in 2011, to this day it remains one of those films I could watch pretty much every day without getting tired of it.

Inevitably, ‘Dawn..’ and ‘Day..’ (both also recorded off TV) followed, then ‘Martin’ and ‘The Crazies’ (bought second hand on Redemption VHS). All of these were – and are – fucking brilliant, and by this stage in my descent into cinema fandom, Romero was The Man as far as I was concerned.

In my mind, I built him up as a truly heroic figure, and never tired of telling people how great I thought he was. Conspicuously ignoring some of the more errant entries in his filmography, I saw him as the guy who never put a foot wrong – this bad-ass auteur who systematically rejected Hollywood bullshit, but wasn’t some pretentious arthouse type either. An underappreciated genius who had to fight to make his films, and who only ever rolled camera when he was sure he could do so on his own terms, with his own people – that’s how I saw it. Mighty George Romero, shakin’ the world once or twice a decade with works that were intelligent, imaginative, exciting, fast moving, socially conscious, harrowing, anti-authoritarian and authentically (though not gratuitously) violent. He made movies that treated their audience with respect, and didn’t let them down. A filmmaker of the people! A Cassevetes of the grindhouse!

And, as far as the selected canon of films I’ve referenced above is concerned, I think such hyperbole is still entirely justified, to be honest. But, had I dug deeper and come up with some of the maestro’s, uh, let’s say, slightly more questionable projects (‘There’s Always Vanilla’, ‘Two Evil Eyes’, ‘The Dark Half’, etc.), my enthusiasm might have been more sensibly tempered for his 21st century comeback.

As it was though, my anticipation when ‘Land of The Dead’ was announced was into the stratosphere. I had faith. And so, needless to say, I was pretty devastated when finally I saw the damn thing.

I know ‘Land..’ has gained some degree of retrospective appreciation within horror circles since its release, but at the time I hated every single thing about it, and have never had the stomach to revisit it. That The Great George A. Romero could take probably one of the biggest budgets he’d ever been accorded and return with a bunch of crap that resembled one of the dumb direct-to-video flicks I’d rent to kill time in the late ‘90s was a disappointment I just couldn’t even comprehend.

Today of all days though, we should probably draw a veil over the past few decades of creative frustration and disappointment, and just reflect that, hey, how many great independent/genre filmmakers *didn’t* hit similar brick walls after the year 2000? (I’m no industry insider, but suffice to say, I don’t think it was mere personal failings that similtaneously stopped the wheels rolling for Carpenter, for Argento, for Lynch, Franco, Hooper, Don Coscerelli, Ken Russell… and so the list goes on.)

Nowadays, I hope I have managed to attain a somewhat more nuanced take on Romero’s legacy, and am happier to embrace the strange and sometimes misguided places that his idiosyncratic approach to filmmaking took him in-between his aforementioned ‘hits’.

Looking over Romero’s filmography today, by my count he directed seventeen films, of which *seven* could conceivably be termed masterpieces – a hit rate not many Hollywood directors could compete with, and an especially remarkable achievement given the marginal/cash-strapped circumstances under which he usually worked.

Thus far unmentioned amongst those golden seven, I have of course come to love 1982’s ‘Creepshow’ as a wonderful Friday night horror flick, a total 180 from the stark realism of his other horror films and one of the best ever attempts to transfer a comic book aesthetic to film, but the one I keep coming back to, and that I immediately wanted to watch again upon hearing the news today, is ‘Knightriders’ – one of the most ambitious, and undoubtedly the most personal, project on Romero’s CV, and arguably his defining statement as a director, from a purely auteurist standpoint.

It is, admittedly, a hugely indulgent, over-long, melodramatic, shamelessly self-mythologising piece of work – but when it comes to a director like Romero, I’m willing to indulge. As a two hour plus tribute to the kind of independent creative spirit in which he believed, and to the extended filmmaking family in Pittsburgh who helped him realise his vision, ‘Knightriders’ is a uniquely moving film. The celluloid equivalent of a ragged victory banner waving in the breeze, it was doomed to commercial failure from its very inception, and is all the better for it.

In fact, I would go as far as to say that, if you’re thinking of paying tribute to Romero by watching some of his films this week, perhaps put the zombies to one side for five minutes and instead cue up‘Knightriders’ for a broader appreciation of the man whose voice and vision American cinema has lost this week. (And when ol’ Ed Harris returns to claim his crown at the end, there won’t be a dry eye in the house, I’m telling you.)

R.I.P.

Wednesday, 12 July 2017

Toei Trailer Theatre # 1:

I AM THE WOLF MAN –

PROUD AND GENTLE-HEARTED.

I AM THE WOLF MAN –

PROUD AND GENTLE-HEARTED.

We jump here from Nikkatsu’s trailer department to that of their ‘60s rivals/’70s successors for the title of “Japan’s coolest movie studio”, Toei – basically just in order to give me an excuse to write a few words about ‘Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope’ (Kazuhiko Yamaguchi, 1975).

I was contemplating a full length review of this remarkable motion picture, but, having revisited it this weekend, I honestly don’t think there is much I can say about the film that will not be made immediately apparent by the act of watching it. (If ever a work of art spoke for itself, etc.)

Essentially I think, ‘Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope’ represents a kind of platonic ideal of everything a “cult movie” can and should be – all the more-so given that, as with most of Toei’s admirably unpretentious output, it was more than likely knocked out in a couple of weeks for a hypothetical audience of adolescent manga fans and boozed up salarymen, without the slightest notion that it would still be attracting attention over four decades later.

When I first encountered ‘Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope’ last year, via a slightly iffy fan-subbed download of a Japanese TV broadcast, it blew me away to such an extent that I could barely even take it all in. Returning to it for a second time, I decided to take a slightly more methodical approach and test my initial hypothesis that this is a film in which every single moment of screen time has something awesome happening in it.

Did it pass the test? Well, let's put it like this - there’s a brief scene early in the film, shortly after Sonny Chiba’s character Inugami-san witnesses a member of defunct rock band The Mobs being torn to pieces by an invisible tiger on the streets of Tokyo, when he is taken in for questioning by the police. This scene, which lasts about two minutes, is not especially awesome, although it does attain the level of ‘mildly awesome’ in the fan-subbed version, whose translation has one of the police officers declaring, “A spectral slasher? Seems to be the only explanation!”.

Aside from that, everything else that happens in ‘Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope’ is categorically, unreservedly awesome. It puts the pedal to the floor right from the outset, and barely lets up for a second.

By the grace of the international film copyright gods, it is also now available in the US and UK as a blu-ray/DVD combo pack from Arrow, so you have NO EXCUSE for failing to verify these findings for yourself.

‘Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope’ – watch it, live it, love it.

(Ok, perhaps don’t “live it”.)

Labels:

1970s,

action movies,

film,

gore,

horror,

invisible tigers,

Japan,

Kazuhiko Yamaguchi,

Sonny Chiba,

Toei,

trailers,

Werewolves

Monday, 3 July 2017

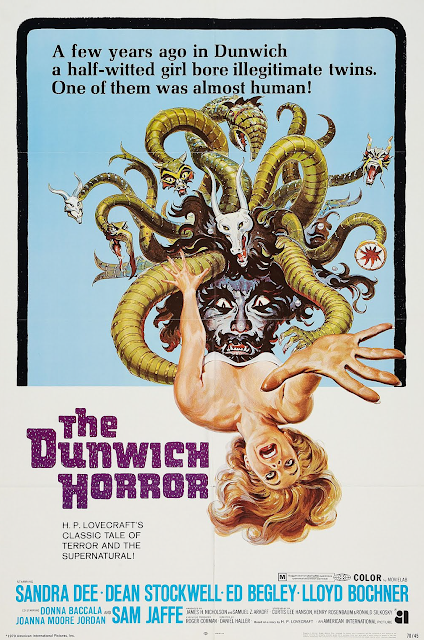

Lovecraft on Film:

The Dunwich Horror

(Daniel Haller, 1970)

The Dunwich Horror

(Daniel Haller, 1970)

“They walk unseen and foul in lonely places where the Words have been spoken and the Rites howled through at their Seasons. The wind gibbers with Their voices, and the earth mutters with Their consciousness. Kadath in the cold waste hath known Them, and what man knows Kadath? The ice desert of the South and the sunken isles of Ocean hold stones whereupon Their seal is engraven, but who hath seen the deep frozen city or the sealed tower long garlanded with seaweed and barnacles? Great Cthulhu is their cousin, yet he can spy Them only dimly. Ia! Shub-Niggurath! As a foulness shall ye know Them. Their hand is at your throats, yet ye see Them not; and Their habitation is ever one with your guarded threshold.”

- Adbul Alhazred

DR CORY: And you really think young Whateley might believe all of this..?

DR ARMITAGE: The book… the girl… I don’t know what to think!

¬ The Dunwich Horror (1970)

I.

Whilst I don’t get the impression that Daniel Haller exactly set the box office aflame with his H.P. Lovecraft-derived directorial debut Die Monster Die! in 1965, the top brass at American International Pictures nonetheless saw fit to award him another, somewhat higher profile, shot at the prize a few years later.

This decision perhaps reflects the fact that the boom in paperback editions of the Lovecraft’s work had succeeded in making him a far more saleable name by the end of the decade than had been the case when the studio insisted on rebranding The Haunted Palace as a Poe picture back in ’63, but nonetheless, the process that eventually led to ‘The Dunwich Horror’ reaching screens in 1970 was long and convoluted indeed, with numerous cultural currents eventually coalescing into one of the most compellingly weird films AIP ever made.

The movie as it finally emerged is certainly a far cry from what was envisioned when the idea of the adapting ‘The Dunwich Horror’ was first mooted back to the early/mid ‘60s, when a draft script outline – unfeasibly titled ‘Crimson Friday’ – was apparently passed to none other than Mario Bava, with the intention that he would direct, with Christopher Lee and Boris Karloff both signed up to star, in a loose continuation of the success the Italian maestro had already brought to AIP via their U.S. releases of his ‘Black Sunday’ (1960) and ‘Black Sabbath’ (1962).

What happened next is a matter of rumour and conjecture, but we can only assume that the souring of relations between AIP and Bava following the fiasco surrounding the disastrous ‘Dr. Goldfoot & The Girl Bombs’ (1966), combined with Bava’s disinclination to make films outside of Italy and AIP’s simultaneous decision to distance themselves from Italian ventures in order to shift resources to their British operation under Louis M. Heywood, led to this tantalising prospect quietly disappearing over the horizon into oblivion.

(Interviewed shortly after the fact, Lee reported that he had actually seen the provisional script for the ‘Crimson Friday’ project, stating that, whilst he liked the idea, it still needed a great deal of work. He also claimed that “Boris didn’t like it”, which can’t have helped matters.)(1)

Needless to say, the evaporation of this dream project remains one of the great ‘what if’s of horror movie history. Both of Bava’s biographers (Tim Lucas and Troy Howarth) seem to have independently verified that the director was indeed a Lovecraft fan (presumably encountering his work in translation via his life-long readership of pulp SF magazines) and, given the incredible alien vistas he had recently conjured out of thin air on 1965’s ‘Planet of the Vampires’, it is frustrating in the extreme to imagine what Bava might have achieved on a full-blooded, respectably-budgeted Chtulhu Mythos movie, if only he had been given the opportunity – but sadly it was not to be.

After this initial idea fizzled out, the impetus to adapt ‘The Dunwich Horror’ seems, like some appropriately tentacled monstrosity, to have split in two, mutating into separate AIP-affiliated projects on either side of the Atlantic. Lee and Karloff were both retained on the British end, and were eventually joined by Barbara Steele and Michael Gough for a co-production between AIP’s UK wing under Heywood and Tony Tensor’s Tigon Productions.

Along with its top-billed stars, the exultant title of the resulting movie retained at least one word from the treatment for the earlier Bava project, as ‘The Curse of the Crimson Altar’ (shortened to ‘The Crimson Cult’ for US release) limped into cinemas in December 1968 to conspicuously little adulation.

The script for ‘..Crimson Altar’ - presumably an entirely different affair from the one referenced by Lee - is alleged to have started life as an attempt to adapt Lovecraft’s ‘Dreams in the Witch House’, but, by the time it reached the screen, so little of that story remained that this source was no longer even acknowledged in the film’s credits. Which, thankfully, spares me the necessity of derailing this review strand to cover a film that carries a justified reputation as one of the most heinous examples of wasted potential in the entire genre.

By handing what was once mooted as a Mario Bava project to British b-movie workhorse Montgomery Tully, Heywood and Tenser achieved the horror movie equivalent of getting George Formby in to record some vocals because Scott Walker can’t make it to the studio, and – barring perhaps the extraordinary sight of Barbara Steele as a green-painted demon princess being attended to by some sort of horned blacksmith in leather fetish gear in an early dream sequence – ‘..Crimson Altar’ has remained a crushing bore on each of the several occasions I have troubled to watch it over the years.

II.

Back in the states meanwhile, the idea of launching a proper ‘Dunwich Horror’ adaptation was still lurking in the long-term memories of AIP head honchos Sam Arkoff and James Nicholson, and, when a certain other movie about a mother forced to give birth to a demonic child started doing gangbusters at the box office in the summer of ’68, it’s easy to speculate that they suddenly remembered they had a similar property of their own knocking about in a dusty filing cabinet somewhere.

And indeed, the version of ‘The Dunwich Horror’ that made it to the screen in 1970 does play up the ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ angle to a significant extent, expanding on scenes merely implied by Lovecraft to give us a fuller picture of the sorry fate of Lavinia Wheatley, mother of Wilbur and his nameless brother.

One of the few women to play any role whatsoever in a Lovecraft story, in print poor old Lavinia rather bears the brunt of the author’s apparently bottomless disgust at the idea of rural working class ‘degeneracy’, which, combined with what we might well diagnose as a somewhat conflicted attitude toward the fairer sex in general, leads him to variously describe her as “somewhat deformed”, “unattractive”, “sickly”, “twisted”, “feeble-minded”, “misproportioned” and “slatternly”, all within the space of a few pages.

Though her role in Haller’s film is scarcely much larger, Lavinia (played by Cassevetes regular Joanne Moore Jordan) is at least somewhat more sympathetically portrayed. Much in the Rosemary mould, she is an unwitting victim of her deranged father’s sorcerous schemings, consigned to an asylum following the trauma of her twins’ unholy birth (a scene at least partially dramatised in the opening scene and animated title sequence), and left to rot as young Wilbur is raised under the tuition of his grandfather, until Dunwich’s ever-present whippoorwills eventually return to claim her soul.

These scenes are amongst the most effective in the film, adding a touch of genuine gothic poignancy to what is otherwise a fairly way-out concoction of craziness, but, thankfully, there was a hell of a lot more being fed into Haller’s adaptation than a mere desire to emulate of Polanski’s hit, even if that was the impetus that secured its place on the production slate.

Most crucially, if we assume that the Lovecraft name had indeed become a potentially saleable asset during the latter part of the ‘60s, I believe the “light bulb moment” that led to ‘The Dunwich Horror’ becoming such an unusual proposition must have resulted from the film’s producers giving some thought to the question of who exactly was buying it.

Their answer, to not put too fine a point on it, seems to have been HIPPIES.

Whether or not this assumption was a fair one is a discussion liable to take us somewhat beyond the remit of this post, but, let’s just say that the general feeling at the time seems to have been that the Lovecraft paperbacks whose frequently mind-bending artwork was infiltrating shelves across USA and beyond were being embraced by the same turned out (or at least, wishing-to-be-turned-on) readers who were busy propelling Pauwels & Bergier’s ‘The Morning of the Magicians’, J.R.R. Tolkien, Carlos Castaneda and Robert Heinlein’s ‘Stranger in a Strange Land’ up the sales charts, as part of the first wave of the ‘new age’ publishing boom that would reverberate through the 1970s and beyond.

With this clearly in mind, AIP seem to have seen an opportunity to cross-breed two of their more successful production strands, and ‘The Dunwich Horror’ thus became the first – and indeed, the only - real attempt to merge the studio’s line of gothic horror films with the parallel strain of counter-culture informed youth movies that Roger Corman had kicked off for them with ‘The Wild Angels’ in ‘66, retooling their now thoroughly outmoded hot-rod/beach party teen flicks for the psychedelic era with envelope-pushing titles like ‘The Trip’ (1967) and ‘Psych-Out’ (1968).

If the combination of the Cthulhu Mythos, drive-in exploitation and LSD-fuelled pseudo-spirituality sounds like a heady brew, well, so it proved to be, and, for all its missteps and wild tonal uncertainty, historical uniqueness alone ensures that, for viewers attracted by this kind of potent, pop-cultural cross-fertilising hullaballoo, Daniel Haller’s movie does not disappoint.

III.

Whilst Howard Philips Lovecraft was certainly no one’s idea of a psychedelic guru, the sheer strangeness of many of the ideas and images he packed into his stories could actually be seen to jibe quite well with the drug-damaged, day-glo concerns of late ‘60s California, and, though ‘The Dunwich Horror’ is pure-bred American pulp fiction, devoid of the decadent/symbolist influences that informed earlier stories like ‘The Festival’ and ‘The Hound’, it was nonetheless a surprisingly good choice in this respect.

Though it is often pegged as one of the more accessible and eventful of Lovecraft’s core mythos tales, I’ve always felt that ‘The Dunwich Horror’ is also one of his most genuinely unhinged things HPL ever wrote – a furtive, uncouth, heavy-handed and frequently absurd piece of prose that comes about as close as his work ever did to reading like the outpourings of a deranged mind (those interminable ‘Dreamland’ novellas notwithstanding).

Certainly, by the time readers have made it through fifty-odd pages of fevered, random adjective-splattered authorial invective, ranting hillbilly dialect, descriptions of half-yeti, half pineapple miscreants who somehow pass for human beneath oversized clothes and covens of elderly academics yelling alien exorcism catechisms at invisible clouds of gas…. well, they’d be forgiven for feeling as if they’ve been slipped a dose of acid at the best of times, to be honest.

Despite the shift to a present day setting, and despite an ensuing injection of sexuality, easy-living and above all WOMEN into proceedings that would no doubt have horrified Lovecraft beyond words (as indeed it horrified the more humourless segments of his literary fanbase for years to come), much of the strangeness of the original story - in terms of both tone and content - is actually retained by the film adaptation.

To their credit, Haller and his collaborators seem to have realised that horror movies (and audience expectations thereof) were experiencing just as much of a period of flux as every other aspect of American culture at the dawn of the 1970s, and as such, no sop whatsoever is offered to viewers anticipating the familiar, dusty paraphernalia of the Poe/Price pictures.

Whilst ‘The Haunted Palace’ and ‘Die Monster Die!’ were both hesitant to fully embrace the weirder aspects of their subject matter (and The Shuttered Room jettisoned it altogether), ‘The Dunwich Horror’ has no such qualms, sidestepping the cob-webbed gothic hangovers we might have expected of a late ‘60s AIP horror and instead standing proudly as something that at the time was entirely new - the first (and for several decades thereafter, ONLY) full-blooded Cthulhu Mythos movie to reach cinema screens anywhere in the world.

Christian cosmology remains absent throughout, and traditional gothic trapping are never given much of a look-in either, as the quasi-science fictional nature of the Great Old Ones and the lore that surrounds them is vigorously and repeatedly outlined by the film’s characters, with at least some of the pungent dialogue assigned to Dean Stockwell’s Wilbur Whateley and Sam Jaffe’s Old Man Whateley taken directly from the more hair-raising passages of Lovecraft’s story.

A few throw-away details (Wilbur's use of tarot cards, the horned demon figure that appears in Sandy Dvore’s animated credits sequence, the Whateley family sigil that looks like some kind of kitschy Native American design) suggest that not everyone working on the film necessarily understood what they were supposed to be going for, but, when the time comes for some no-holds-barred Lovecraftian horror bits, they certainly go for broke.

With the possible exception of Cry of the Banshee (released the same year), ‘The Dunwich Horror’ is the only one of the ‘60s AIP horror films I can think of which features multiple killings, complete with extraneous characters wondering around to act as victims (another sign of the changing times).

Thus, when Sandra Dee’s character’s ill-fated best friend (played by Donna Baccala) makes the regrettable decision to open the much-ballyhooed locked room in the Whateley house, she is met, not with the moth-eaten werewolf claw or iffy ‘mutant’ make-up we might have expected, but with a veritable riot of flashing, solarised colour, deranged, unearthly synthesizer shrieking and loopy lo-fi monster effects, all cut too fast for us to get any clear picture of what’s actually going on.

Replaying the sequence frame by frame reveals that flailing scraps of carpet, rubber snakes and imitation chicken feet were all potentially in play, and, crude though such inclusions may seem when examined in any detail, it is safe to assume that contemporary cinema audiences would have had no such time to make sense of what they were seeing, and the overall effect is quite startling - as good an attempt to “film the unfilmable” as could be wished of a 1969 film working under obvious budgetary limitations.

In fact, it is difficult to imagine just how bizarre ‘The Dunwich Horror’ must have seemed to an audience coming to the film with no knowledge of Lovecraft’s writing. Many years after I watched it for the first time, it still thrills me more than I should really admit to to hear (sort of) famous actors in a (sort of) Hollywood movie throwing about the dread names of Yog-Sothoth, The Necronomicon and so on, their delivery balanced on a knife edge between baffled camp and deadly seriousness, whilst at the same time a surprisingly effective gigantic, invisible, tentacled creature rampages through the night-haunted New England hills, with Dr Henry Armitage of the Miskatonic and his cohorts in hot pursuit.

IV.

One of the major problems in adapting ‘The Dunwich Horror’ for the screen is the fact that the story essentially has no central character or audience surrogate figure. Like many Lovecraft stories, events are recounted from a distance, as if recounted as part of some cracked, deeply subjective chronicle of local history.

Dr Armitage, who represents the nearest thing the tale offers to a ‘hero’, doesn’t even turn up until the tale’s final act, and even then, the elderly Miskatonic University librarian is closer to a human deus ex machina than a relatable character. Meanwhile, Wilbur Whateley, whose short and tempestuous earthly life is recounted in the opening half of the tale, is an eight foot tall monstrosity dedicated to the downfall of mankind, who grows to full maturity within ten years of his birth and barely retains the illusion of humanity by means of voluminous, tightly-buttoned clothing and croaking English utterances forced from his alien vocal cords.

Described on about twelve separate occasions by Lovecraft as “goatish”, something tells me Wilbur wouldn’t exactly have been cat-nip to Hollywood’s aspirant young actors when they checked out the story prior to deciding whether or not to accept the offer of a top-billed role from AIP – and indeed, rumour has it that the list of stars who turned down the part, from first choice Peter Fonda on down, was long indeed.

Of course, the choice of Fonda goes some way toward indicating the direction that the film’s writers (including future director Curtis Hanson) wisely took in order to make their adaptation both more commercially viable, and more relevant to its intended audience.

Rather than reluctantly accepting Armitage as the protagonist, casting whichever one of the big horror stars had a few spare months to fill and scripting an hour’s worth of wood-panelled studies and brandy glasses (as would inevitably have been the case a few years earlier), the writers instead took the braver option of going with the younger, more oppositional figure of Wilbur, humanising him to the extent that the bestial, shambling terror described by Lovecraft eventually evolved into the somewhat more presentable form of… Dean Stockwell.

A former child actor (memorably playing the title role in Joseph Losey’s ‘The Boy With Green Hair’ in 1948), Stockwell was still far from a household name in 1970, having worked in film and TV only sporadically during the ‘60s, whilst he meanwhile pursued his primary gig as a visual artist and participant in Hollywood’s thriving counter-culture/rock scene. It was this latter connection that likely won him the role of a rooftop-dwelling Haight Ashbury mystic in Corman’s ‘Psych-Out’, and it was presumably his memorably enigmatic performance there (arguably stealing the movie from Jack Nicholson and Bruce Dern) that brought him in turn to ‘The Dunwich Horror’.

Although Stockwell was reportedly pretty far down AIP’s list of potential leading men, his oddball charisma made him perfect for the kind of callous ‘anti-hero’ protagonist the film needed, and I would go as far as to say that, whether by accident or design, his casting was nothing less than a stroke of genius.

Given what seems to have been a pretty free hand in developing his own character for the film, and with nothing much to go on from the source text (beyond “goatish”), Stockwell completely succeeds in transforming a scheming, inhuman disciple of the Great Old Ones into a compelling central figure, delivering what, in my view, stands as one of most extraordinary performances in any ‘60s horror film. Had the film been more of a success, it should by rights have launched Stockwell immediately into the big leagues - at the very least as a natural successor to the era’s aging ‘horror-men’.

Aside from anything else, character Stockwell builds around Wilbur is just so *funny* – a self-made, self-aware warlock of sophisticated tastes and aspirations, ready to rise above his humble redneck origins and attain a touch of aristocratic grandeur… if only his wretched old grandpa didn’t keep bumbling about, getting in the way; Lovecraftian horror’s answer to Harold Steptoe, no less!

There is a bit of a ‘precocious school-boy’ vibe about him; his supreme self-confidence and powers of persuasion feel entirely ‘book learned’ and, when Sandra Dee’s character falls under his spell, there is a sense that he can’t quite believe his carefully-honed occult pick up techniques have actually worked and snagged him a real life pretty lady.

Though it was probably more accidental than deliberate [see further discussion in part VII below], I love the way that disparity between the shambolic hillbilly frontage of the Whateley house and its grand, stately interiors creates the impression that Wilbur must have redecorated the place single-handedly to aid his ‘hot young warlock’ self-image.

In fact, one of my favourite moments in the whole movie comes when, having seated Sandra in his impressively upholstered fire-side reception area and offered her some tea, Wilbur (who clearly wishes he could summon his loyal servant, Vincent Price style) nips off into a shabby, tract home kitchen complete with lace curtains and match-lit gas stove, emerging a few minutes later with her beverage (drugged, of course) presented upon a magnificent silver serving platter.

As this last point reminds us, discussion of the more comedic aspects of Stockwell’s characterisation should not distract us from the fact that he is also an exceptionally sinister presence. Never remotely sympathetic, he maintains that difficult balance between being purely villainous and inexplicably likeable, suggesting that all those hours Wilbur no doubt spent practicing his chops in front of the mirror before heading off to Arkham in search of the Necronomicon and a handy virgin or two have clearly paid off.

As far as evil sorcerers go, his hypnotic gaze is second to none, and his hand gestures and sacrificial dagger twirling technique should rightly be the stuff of legend. I realise that lengthy ‘cult ritual’ scenes can be a bore for many viewers, but I promise you – when Stockwell is workin’ the altar here, you’ll be willing to watch him for hours.

(In my dreams, I imagine a cross-over sequel in which Stockwell’s Wilbur is pitched against Andrew Prine’s Simon, King of the Witches in the ultimate hippie warlock showdown, but sadly it was not to be.)

VI.

Following the pattern established by all three of the Lovecraft adaptations that preceded it, it was deemed necessary to add a blonde heroine/damsel-in-distress figure to ‘The Dunwich Horror’, and, as mentioned above, this vacancy was filled by Sandra Dee – a former teen star who had attained a certain amount of fame playing the titular character in the hit beach comedy ‘Gidget’ (1959), followed by ‘A Summer Place’ (also ’59) and numerous pictures of a similarly breezy nature. Sadly for any lovers of early ‘60s kitsch in the audience, Dee did not return for ‘Gidget Goes Hawaiian’ in 1961, and by the time she accepted her role in ‘The Dunwich Horror’, several years had elapsed since her last screen appearance (in ‘Doctor, You've Got to Be Kidding!’ (1967)), suggesting that her career might already have been in choppy waters. (2)

As we might well have anticipated, Dee’s thankless role as Wilbur’s victim/lover Nancy didn’t seem to do much to calm the raging waves of career oblivion, especially given that, in an example of hippie-era creepo coercion that exactly mirrors the methodology of Stockwell’s character, she is expected to do *quite a lot* of rather undignified stuff in ‘The Dunwich Horror’, carrying the weight of an uncomfortable swerve toward softcore eroticism that somehow manages to leave the film feeling far sleazier than many of the more explicit horror pictures that followed in the 1970s. (3)

Wilbur’s extended ‘seduction’ of Nancy certainly represents a classic skeevy hippie creep operation, as he takes the lead in the pair’s lengthy, soul-searching philosophical chats, nattering on about sex and repression and psychoanalysis, making much of his ‘open’ and ‘modern’ attitudes whilst simultaneously steering things in his own, crudely manipulative, direction.

Wilbur’s veneer of urbane, soft-spoken erudition and faint air of dignified self-pity is immediately betrayed by the covetous look in his mad, staring, perma-glazed eyes, meaning that he is fooling no one, basically – except Nancy that is, for whose benefit the script-writers throw in suggestions of drugs and hypnosis to cover up for the fact that her attraction to a suitor as obviously malign as Wilbur otherwise feels utterly implausible.

What grates here however is a suspicion that Wilbur’s unsavoury approach to lovin’ is shared to some extent by the film itself. A ludicrous dream sequence, in which Nancy is interminably chased around by a bunch of body-painted slathered cavemen/nightmare hippies, seems like a laborious way to establish the fact that SHE’S REPRESSED - and, as is set out in Hippie Misogyny 101 (Professors Miller & Kerouac consulting), the best way to straighten out an uptight chick is obviously to fuck her.

This Wilbur accomplishes via a second, somewhat more convincing, dream/hallucination sequence, wherein faceless, black-cowled cultists appear alongside him as he presides over Nancy’s robed body on the altar slab of the cliff-top ‘Devil’s Hop Yard’ set. Here, ‘The Dunwich Horror’ becomes the first horror film I can think of to extend the symbolic rape of the ‘sacrificial victim’ scene beloved of all Satanic cult stories into an actual rape, incorporating not only a furtive bit of cloth-covered boob-fondling, but also what by any measure is far too much footage of Dee’s writhing, naked thighs (and I’m speaking here as a Jess Franco fan, so, believe me – this one ‘writhing thighs’ shot really is used a lot).

Complementing the tone of leering unwholesomeness established by this sequence is the later ‘tentacled evil twin attack’ [described in part III, above], which concludes with a strong suggestion that the monster also rapes its victim – an utterly gratuitous addition that, as with the similarly sleazy ‘Cry of the Banshee’, serves only to handily signpost the retreat of censorship at the dawn of the ‘70s whilst also cementing my suspicion that, like its central character, ‘The Dunwich Horror’s thin veneer of enlightened sexual freedom hides an approach to gender that is just as fearful and sophomoric as that of Lovecraft.

VII.

Before we move on (and lord knows, it is definitely time to move on), we should probably take a few minutes to talk about the film’s curious supporting cast. By this stage, it was an established tradition for these AIP horror films to offer roles to ailing Old Hollywood character players (not only Peter Lorre and Lon Chaney, but Elisha Cook Jr, Joe E. Brown and beyond), and, as the producers of ‘The Dunwich Horror’ reached further afield, the players they acquired in this bracket scarcely helped make the film any more normal, let’s put it that way.

At the age of 79, Sam Jaffe – a truly legendary New York stage actor and a veteran of ‘The Asphalt Jungle’, ‘Gunga Din’ and ‘Ben Hur’ amongst many others – proves a particularly odd presence as Old Man Whateley. Whilst he certainly gives it his all, the poor chap just never seems to ‘fit’, shuffling about, hoarsely shouting his dialogue straight to camera, and generally giving every indication of having absolutely no idea what he’s doing in this movie. As a result, his character is far too scatter-brained and sympathetic to ring even remotely true as the callous sorcerer patriarch whose cracked inter-dimensional breeding experiments caused this whole mess in the first place.

Meanwhile, Ed Begley (yes, father of the ‘80s/’90s comic actor and TV star) takes an unscheduled break from his long CV of police chiefs, corrupt politicians and sweaty industrialists to essay the role of Dr Henry Armitage, looking just as out of place as Jaffe as the story’s retiring librarian turned incantation-wielding exorcist. Though he never gets anywhere near to embodying the soft-spoken academic envisioned by Lovecraft, his characteristically belligerent, two-fisted approach to the role is nonetheless quite enjoyable, especially his stone-faced, sheriff-like determination that that damned Wilbur Whateley ain’t going nowhere with his precious Necronomicon.

(Given that Jaffe was reportedly a gentle, humanitarian mathematician off-screen, whereas Begley gives every impression of being a raging bad-ass, I’d be tempted to suggest that ‘The Dunwich Horror’ might have been benefited from swapping their roles, but frankly this review is long enough already without me offering 50-years-late advice to possibly-deceased casting directors, so we’ll let it slide.)

VIII.

A few years on from ‘Die Monster Die!’, Daniel Haller still doesn’t come across as quite what you’d call a ‘stand-out’ director here, and, conventionally speaking, ‘The Dunwich Horror’ is uneven, slackly paced and generally all over the place. But, he certainly does his best, clearly working hard to try to make each scene memorable and interesting to look at, and that counts for a lot.

As befits the film’s counter-cultural vibe, there is a lot of casually ‘weird’, quasi-experimental camerawork, with deliberately blurred shots, Jess Franco-style drifting, handheld close-ups and some great extreme low angles on Stockwell’s character, whilst every trick in the book is meanwhile employed to make things feel a bit ‘psychedelic’, with hap-hazard super-impositions of crashing waves and sun-light shining through tree-tops, random subliminal jump cuts and masses of filtering and solarisation. (The aforementioned cult rape nightmare/hallucination sequence even seems be shot through a thick cotton gauze, which is… interesting.)

(Whilst we’re on the subject, no explanation is ever given for the weird, glowing, translucent glass objects that Wilbur Whateley keeps on his coffee table. They seem to hold some kind of alien/occult significance – like space-age scrying orbs or something? – but this is never expanded upon. An odd visual non-sequitur whose very inclusion in the finished film tells its own story, they definitely feel a bit “hey man, look what the props guy found in town – far-out!” if you ask me.)

This feeling of psychedelic saturation is aided immeasurably by Les Baxter’s suffocatingly baroque, incessantly repetitive score, which is just off the goddamn hook, quite frankly – an insanely bombastic confection of end-times orchestral exotica and wailing, otherworldly vibrato that does much to anchor the film’s fetid, over-ripe atmosphere, even in its more earth-bound moments.

Elsewhere, signs of Haller’s formidable expertise as an art director are frequently in evidence. The interiors of Whateley house seem to re-use bits of the famously recycled sets Haller accumulated whilst working on the Poe movies (if I’m not mistaken, both the opening birth scene and Nancy’s troubled dreams take place in an extravagently redecorated version of Roderick Usher’s bedroom), and the elaborate matte painting used for the establishing shots of the ‘Devil’s Hop Yard’ (the aforementioned inexplicable cliff top pagan altar upon which Wilbur has his wicked way with Nancy) is absolutely stunning – one of my favourite such efforts in all of ‘60s horror in fact.

Though only seen briefly, the full exterior of the Wheatley house also looks very convincing when freeze-framed – I’m not even sure if it was a real location or a matte job, but either way it’s a shame it wasn’t used more extensively – and the house’s entrance hall, complete with giant sigil in the centre of the floor and shelves of mouldering old blasphemous tomes, is rather nifty too.

In contract to the essentially stage-bound / self-contained nature of Corman’s gothics however, ‘The Dunwich Horror’s plotting necessitates that the film must ramble around all over the place, taking the action considerably beyond the boundaries of these well-turned-out environments, utilising a variety of ad-hoc sets and random locations that never really fit together with one another, making it difficult for Haller to establish the kind of consistent visual ‘world’ upon which the atmosphere of a good Lovecraftian tale so heavily relies. (Even the aforementioned strengths of the production design are undermined when we switch to poorly matched close-ups.)

Furthermore, whilst some of the film’s earlier scenes achieve a respectable level of groovy, Bava-esque mood lighting, much of the rest is over-lit in that particularly flat, artless, ‘60s Hollywood kinda style that reveals pokey sets for exactly what they are and kills any hint of atmosphere stone dead, evincing either a lack of time for proper set-ups, or a lack of imagination on the part of credited DP Richard C. Glouner.

Likewise, the fall-back on ‘trippy’ visual effects does often cross the line into outright goofiness, even for a viewer such as myself, who normally lives for this kind of stuff. (Yes, I’m particularly thinking here of THAT dream sequence with the painted hippies - a weak travesty of the by-now-traditional Poe/Corman dream sequences whose ham-fisted borrowings from ‘60s ‘underground’ cinema ironically render it far less disorientating and psychologically potent than it’s more subtle predecessors.)

Generally speaking though, ‘subtlety’ is not something any sane viewer should expect to find on the menu here. In fact, ‘The Dunwich Horror’ is so gloriously over the top in every respect that it is difficult to even take account of its many flaws upon first viewing, let alone dwell upon them.

Regardless of any discussion re: what does and does not work herein, ‘Dunwich..’, like so many films of its era, feels very much like a project in which both the intent of the filmmakers and the nature of the subject matter found themselves completely subsumed by the cultural currents raging around the time and place in which it was made.

IX.

Location filming for ‘The Dunwich Horror’ took place in Mendocino, California, at the height of that town’s rebirth as a veritable rural retreat for counter-culturally inclined refugees from L.A. and San Francisco (check out Doug Sahm’s 1969 hymn to the joys of life in Mendocino here), and it seems likely that many in the cast and crew, evolving from the always somewhat bohemian Corman circle, considered themselves to be coming from an authentically ‘turned on’ headspace. (4)

Nonetheless though, the cheesy, opportunistic manner in which the film’s hippie vibes manifest themselves aligns it more with the kind of “turned on Hollywood” madness that allowed atrocities like Otto Preminger’s Skidoo to become a reality (funnily enough, it was in that film that Corman reportedly first saw the work of Sandy Dvore, who provided the animated credits sequence for ‘Dunwich..’).

In fact, it could well be argued that, by comparing to the slyly transgressive counter-cultural elements that sneaked into earlier Corman/AIP productions to the more explicitly “way-out” agenda of ‘The Dunwich Horror’, we can see in microcosm how the explosion of the “hippie” aesthetic into the mainstream of American culture in the late ‘60s quickly dulled the edge of its message to the point of blunt self-parody.

Whereas the beatnik satire of ‘A Bucket of Blood’ (1959) and the edgy psycho-analytical subtexts and proto-psychedelic touches of the early Poe films still feel vital to this day, the “anything goes” mentality that prevailed by the time ‘Dunwich..’ went before the cameras resulted in a movie that simply feels bloated, decadent and zoned out.

Any hint of social or spiritual relevance that the filmmakers may or may not have had a yen to convey is rendered vague in the extreme, lost amid the script’s decidedly mixed messages, and further confused by the instant-kitsch barrage of ‘weirdy’ visual effects, faux-hip dialogue and awkward, opportunistic sexual content.

At same time though, the movie still retains a darker edge, largely as a result of Stockwell’s spectacularly sinister performance, and the unsavoury historical resonances that, in retrospect, it can’t help but conjure for us.

If you’ll forgive me some pretty morbid fact-checking: ‘The Dunwich Horror’ premiered in January 1970, having presumably been shot during the preceding spring/summer. The Tate-LaBianca murders took place in August 1969. Charles Manson was arrested, on unrelated charges, in October. From December 1969 onwards, the LAPD began piecing together evidence linking him to the killings, and Life Magazine’s famous cover story – which first gained Manson widespread notoriety – appeared in the same month.

With his Rasputin-like hypnotic gaze, his hipster guru patter and his drug-aided brain-washing and sexual exploitation of vulnerable women, Dean Stockwell’s portrayal of Wilbur Whateley is a clear exemplar of the “evil hippie cult leader” archetype that would soon proliferate through popular culture in the wake of the publicity surrounding Manson’s arrest and trial – but, as the dates above make clear, Stockwell and ‘The Dunwich Horror’s other principal creators were trying this get-up on for size before Manson and his activities become public knowledge, and possibly before his principle crimes were even carried out.

We’re moving into the realm of pure speculation here of course, but it occurs to me that, as turned on, creative cats on the Hollywood scene, this film’s star, writers and director were all potentially in the right time and place to have run into, or at least been aware of, Manson’s “family” and their antics at an earlier stage than most.

Just drawing from my own knowledge for instance, I’m aware that Stockwell was a close friend of Neil Young at around this time [he is credited on Young’s 1970 ‘After The Goldrush’ album with writing the unproduced screenplay that inspired the title song]. Young has subsequently confessed that he remembers ‘partying’ with the Manson girls whilst the “family” were still ensconced at Dennis Wilson’s house, so…. that leaves us just one step removed, for a start..?

Again, I need to stress that, without undertaking closer scrutiny or in-depth research on the subject, we have *nothing definite to go on* when it comes to trying to nail down this extremely tenuous connection, but regardless – you get where I’m heading with this, I’m sure.

And, as obsessive mappers of pop cultural fault lines will no doubt already have noted, this loops us straight back around to the influence that ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ exerted upon the production of ‘The Dunwich Horror’, with the legacy of the former film often haunted by the perception that it in some way constitutes a psychic precursor to the tragic events that befell its director a year or so later.

Between these two films in fact, can we see enacted on screen both the premonitios and after-shocks of the terrible black vortex of Hollywood, August 1969, whose fringes they both skirt..? Or, am I just going way too far with this stuff..? You tell me.

Either way though, the realisation that the makers ‘The Dunwich Horror’ were positing a clearly Manson-esque figure as a horror movie anti-hero whilst, not a million miles away, the genuine article was simultaneously carrying out his most infamous deeds lends the film a more deeply disturbing aura than anything Lovecraft could have envisioned.

X.

As ‘The Dunwich Horror’ rolls on toward its pleasantly rollicking finale – wherein the invisible beast solarises its way through several gun-toting rednecks and Wilbur’s ghastly sex-magick conjurations are interrupted by Dr Armitage, prompting an incantation-slinging showdown so daft it must be seen to be believed – we are liable to find ourselves reflecting on the fact that, though ‘Dunwich..’ constitutes a bit of a one-off, evolutionary dead end within the wider horror canon, it nonetheless exhibits a number of similarities with the small number of other Lovecraft movies that trickled out through the 1960s.

Like ‘The Haunted Palace’, ‘Dunwich..’ ends with the heroine about to sacrificed on an elaborate altar to a shapeless, glowing evil god of some kind (a scenario that Lovecraft never actually used in any of his stories, as far as I can recall), and, as seen in both ‘The Haunted Palace’ and ‘The Shuttered Room’, the old “mutant sibling behind the locked door” trope gets another outing too. (Far from being contained behind the traditional padlocked door, the evil twin in Lovecraft’s story grows to such monstrous proportions that Wilbur eventually converts his entire house into a kind of ‘holding chamber’ for it – an idea which was presumably deemed a touch too ambitious for the movie.)

As we have already noted, all four of the Lovecraft films made to this date chose to override the author’s frequent refusal to even aknowledge the existence of women by parachuting a pretty heroine into the middle of their respective stories. With the exception of Debra Paget in ‘The Haunted Palace’, the other three actresses in question (Susan Farmer, Carol Lynley and Sandra Dee) were all blondes, and all possess a strange, vacant, somewhat doll-like quality that makes them seem almost like variations on the same character.

As a ‘type’, they perhaps tell us more about the role of women in ‘60s horror films in general than anything specifically related to Lovecraft adaptations, but, along with the other recurring tropes outlined above, I believe their repetition through these films nonetheless went on to exert a significant influence upon not just the shape of future Lovecraft adaptations, but the popular perception of what constitutes a “Lovecraft type story” in general – a theme that we will perhaps be able to pick up again in future instalments of this series.

XI.

‘The Dunwich Horror’ was not the final entry in AIP’s loose string of marginally Poe/Lovecraft-affiliated gothic horrors - ‘Cry of the Banshee’ followed in July 1970 and Gordon Hessler’s subsequent ‘Murders in the Rue Morgue’ didn’t arrive until September ‘71. But, this was the last one to be shot in America, and, thematically speaking, it certainly feels like the strange culmination of everything that AIP’s different productions strands had been inadvertently making their way towards since the start of the ‘60s. As such, the symbolic weight of the film’s January 1970 release date seems almost too perfect.

Not only AIP’s horror films, but their ‘beach party’ teen movies, their drug/bikesploitation flicks – all seem somehow to meet, and to collapse in upon themselves within the fabric of ‘The Dunwich Horror’. And, thanks to the intervention of way heavier counter-culture vibes than those that had prevailed when Roger Corman first began filtering hints of beatnik jive into his pictures back in the late ‘50s, they do this in a wilder, weirder and more hair-raising fashion than anyone might have anticipated.

Certainly, as the studio’s leading lights found themselves in the screening room watching a former icon of teen beach comedies writhing in ecstasy with a copy Lovecraft’s Necronomicon between her legs, whilst a bohemian drop-out former child star portrayed a knife-wielding, quasi-Mansonite madman, ranting ceaselessly about extra-dimensional gods as the cloying psychedelic excess of Les Baxter’s maddening score melted minds left, right and centre…. well, is it any wonder that both AIP and executive producer Roger Corman decided enough was enough, and that the time had come to pull the plug on this mutated ‘60s netherzone before things got out of hand?

Within a few years, the U.S. exploitation/drive-in business as a whole had hit the breaks hard on all this hippie horror shit. By ’72, AIP’s production slate was filled with gangsters, kung-fu killers and shotgun-packin’ mamas, whilst Corman, now flying solo with New World Pictures, had his Candy Stripe Nurses and Big Doll House to bring home the bacon. In other words, things were back down to earth with a bump.

And so, where did this leave our hopes for further expeditions into the worlds of H.P. Lovecraft reaching commercial movie screens…? Well, pretty damn high and dry to be honest, but that’s a story for another day when (god help us all) ‘Lovecraft on Film’ next returns. For now, I simply thank you for making it to the end of what is by far the longest of the many over-long posts I’ve written for this blog over the years, and until the next time, Ia! Ia! Yog-Sothoth! Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn!

--------

There’s not a great deal of alternative poster artwork for ‘The Dunwich Horror’ to display here (just about all markets went with a variation on the post at the top of this post, as far as I can tell), but the Black Hole Reviews weblog did dig up this neat bit of pre-production publicity (from Films and Filming, 1969), with Peter Fonda apparently attached to star…

…and then there's this startling publicity still, featuring a topless Sandra Dee being menaced by somebody in an owl mask?! (Nothing of the kind is included in the finished film, needless to say.) I’d love to know the story behind this.

---------

(1) For more info on the ‘Crimson Friday’ project, see Steve Haberman’s highly informative commentary track on the 2016 Shout Factory two-fer blu-ray of ‘The Dunwich Horror’ and ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1971). For info, various others bits of otherwise unsourced production info and speculation included in this review also originate from Haberman’s commentary, so all credit to him for putting in the leg-work re: filling in the background on these otherwise rather overlooked movies.

(2) In her own way in fact, Dee stands as just as much of a Hollywood cult figure as Stockwell, if not more-so. She was immortalised in the song “Look at Me, I’m Sandra Dee” from ‘Grease’ (1978), and her tempestuous marriage to singer Bobby Darin and subsequent fall from grace has been explored in a number of books and films over the years.

(3) Apropos of nothing, it is interesting to note that Dee’s ‘Gidget’ co-star James Darren was treading similarly weird terrain at around this time, as the ill-fated male lead in Jess Franco’s Venus in Furs. Strange times indeed.

(4) Fans of especially eerie period synchronicity may wish to note that the Sir Douglas Quintet video I’ve linked to features some of the last known footage of Sharon Tate, appearing less than a month before her murder.

Labels:

1960s,

AIP,

California,

casual misogyny,

cosmic horror,

cults,

Daniel Haller,

Dean Stockwell,

Ed Begley,

evil twins,

film,

hippies,

horror,

HP Lovecraft,

LOF,

magic,

movie reviews,

psychedelia,

Sam Jaffe,

Sandra Dee

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)