VIEWING NOTE: As per my review of ‘Vampyros Lesbos’, the screenshots above originate not from the blu-ray edition mentioned in the text, but from the 2000 Second Sight DVD.

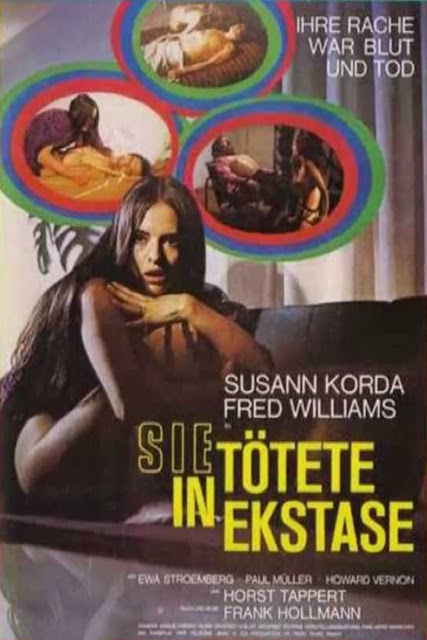

AKAs: Crimes dans l'extase [France & Belgium], Misdaad in Extase [‘Crime in Ecstasy’ / Belgium (Flemish title)], Lubriques dans l'extase [‘Lewd in Ecstasy’/ French poster title], Mrs. Hyde / Dr Jekyll & Miss Hyde [German working titles].

Like its companion piece Vampyros Lesbos, ‘She Killed in Ecstasy’ is a film that didn’t impress me much on first viewing. I chiefly recalled it as being sleazy, sloppy, ugly and implausible, but, revisiting it via Severin’s recent blu-ray edition, I found a lot more to enjoy here than I had anticipated.

Though still a poor sister in comparison to the simultaneously shot ‘Vampyros..’, with an under-cooked narrative and abrupt conclusion that betray the haste with which it was produced, SKIE (if you will) is nonetheless a fine slice of vintage Franco, incorporating a swathe of florid and unforgettable imagery, great performances from several of Franco’s best-loved cast members and – believe it or not – some quite good writing in its first half.

Basically a simplified rehash of The Diabolical Dr. Z (itself heavily indebted to Cornell Woolrich’s perennial ‘The Bride Wore Black’), ‘She Killed in Ecstasy’ begins with rugged young research scientist Dr Johnson (Fred Williams) receiving the academic equivalent of a right kicking, as the boorish and self-righteous members of the ‘medical council’ not only reject his requests for further funding, but proceed to lay into the methodology and morality of his work (which from what little we see of it comprises some Frankensteinian business involving pickled embryos and brightly-coloured test tubes) with a vengeance.

So virulent is the council’s hostility that Johnson (who seems just a *bit* thin-skinned, to be perfectly honest) is reduced to a state of catatonic depression. Seeing no way forward for his work – and apparently oblivious to the restorative charms of his beautiful island villa and devoted and no less beautiful wife (Soledad Miranda) – Johnson eventually takes his own life.

Devastated by her loss, Mrs Johnson (her character is never gifted with a first name at any point in the film, unbelievably) becomes a single-minded instrument of her dead husband’s vengeance. At you might well anticipate at this point, the life expectancy of the members of the aforementioned medical council (comprising a Franco dream-team of Howard Vernon, Paul Muller, the director himself and Ewa Stromberg from ‘Vampyros..’) just took a turn for the worse, and a synopsis of what happens during the remainder of the film is largely surplus to requirements.

From the perspective of a first world democracy, the manner in which Dr Johnson’s treatment by the medical council is played out in SKIE seems exaggerated to an almost comical extent, and indeed, that was certainly my impression when I first viewed the film. Rather than simply rejecting his request for funding on ethical grounds and calmly moving on to their next item of business, the learned gentlemen (and lady) of the council are apparently so outraged by Johnson that it is implied they break into his home, and, “raging like madmen” according to the English sub-titles, proceed to destroy his laboratory and rough up his wife, before calling a press conference specifically in order to denounce him as a monstrous charlatan.

And for Dr Johnson’s part meanwhile, rather than shrugging off this shabby treatment and making efforts to find support for his research elsewhere, he immediately seems to collapse into a state of complete despair, as if the possibility of his continuing his work through channels other than those overseen by this conclave of grumpy old naysayers is completely inconceivable.

Admittedly, a minor disagreement over professional ethics in medical research wouldn’t have provided much meat for a decent exploitation movie, but still, the hysterical over-reaction of both parties as we approach the tragedy that catapults Miranda’s character onto a path of obsessive vengeance initially seems absolutely ridiculous - until that is, we remember that Franco did *not* make this film in the context of a first world democracy.

Although it was financed internationally (as were just about all of his films from the mid ‘60s onwards), ‘She Killed in Ecstasy’ was still conceived and shot within a totalitarian state, in which the excessive treatment meted out to Dr Johnson by the medical council more than likely *did* reflect the attitude of the regime toward outbursts of progressive or controversial thought, whether in the fields of science, culture, or indeed cinema.

Viewed within this context, the portrayal of Johnson’s destruction by the establishment – though still painted with what might generously be termed ‘broad brushstrokes’ – actually becomes quite harrowing, and, if the circumstances that led to his suicide are still somewhat unconvincing (hey dude, it sucks that The Man’s put a nix on yr research, but you’re still living in a space-age bachelor pad with Soledad Miranda and some of grooviest shirts ever created – there’s a lot to live for), the anger that lies behind this tale of a man’s dreams being senselessly crushed by vindictive bureaucracy was no doubt still something that Franco and his fellow countrymen could feel very keenly whilst Spain was still under the thumb of his namesake’s corrupt and hateful regime.

Key to selling us on the more familiar revenge movie tropes of the movie’s second half meanwhile is a characteristically excellent performance from Miranda – surely the best of her tragically brief career, alongside ‘Vampyros Lesbos’. Whilst, as noted, the circumstances of her husband’s death still seem slightly contrived, her portrayal of the loss and desolation that consume his wife is entirely convincing, whilst her mental disintegration as she transforms herself into a single-minded instrument of vengeance is definitely one of the better realisations of this over-familiar motif in the annals of b-cinema.

Basically, the sheer force of Soledad’s presence in this role is quite a thing to behold. A brief scene in which she stands alone, staring out to sea after her husband’s death and reciting a strange litany of romantic desolation (“I am searching for you my love, even if it is only your dream caressing me..”), is extremely affecting, distantly recalling the breathtaking beachside excelsis of Francoise Pascal in Jean Rollin’s La Rose de Fer, whilst the sheer depths of burning contempt in her coal-black eyes as she subsequently contemplates her vengeance rivals that of the great Meiko Kaji in her numerous similar roles.

Also worthy of praise here is Howard Vernon, whose terrifically hateful characterisation renders him the most fleshed out and genuinely dislikeable of Soledad’s victims. Though still anchored firmly in comic book villain territory, it’s great to see Vernon taking the opportunity to essay a role with a little more nuance than the mad doctors and vampire overlords he more frequently provided for Franco.

A delightfully hypocritical and smarmy, yet still somehow charming, creation, your blood will fairly boil as Vernon’s Professor Walker sits at a hotel bar feeding a credulous young female journalist some fatuous rubbish about the morality of young people being warped by mind-bending drugs and sexual license, before he immediately sidles over to Soledad’s table following the journalist’s departure, his cocktail-boosted ego blinding him to both to the obvious hatred in her eyes, and to her identity as the widow of the man whose career he so recently ruined, as he sets in on what is obviously his favourite pre-scripted playboy seduction routine (“excuse me, but have we met somewhere before? Buenos Aires? Montevideo?”).

I bet the dusty old goat can’t believe his luck when his tired lines actually appear to work, and, presently, his self-deluding insistence upon saying his prayers before letting his casual pick-up get into bed with him adds the perfect crowning note to this most craven and despicable of characters. Played out by performers of the caliber of Miranda and Vernon, Walker’s subsequent bloody demise is both the most satisfying and most violent of Mrs Johnson’s assorted acts of vengeance. (1)

Though it doesn’t quite reach the same grisly heights, our heroine’s lesbian seduction of Ewa Stromberg’s Dr. Crawford is nonetheless a masterpiece of kitsch. Bonding over a copy of John LeCarre’s ‘A Small Town in Germany’, the pair’s feigned jetsetter ennui is almost comical, whilst their awkward slide into Sapphic groping within the stark, mod interior of the Bofill buildings reaches a climax of grotesque hilarity as Soledad (wearing an unflattering blonde wig for the occasion) suffocates Ewa with a transparent op-art plastic cushion. (2)

It’s difficult to imagine a more exquisite ‘euro-trash’ moment, and indeed Franco plays up the camp for all it’s worth. Nonetheless though, he still somehow manages to unexpectedly crow-bar in a curious exchange of dialogue between the two women that, whether consciously or otherwise, seems to function as a perfect vindication of the director’s particular approach to cinema; “What does it mean?” asks Stromberg, discussing one of the paintings that adorn the walls. “Whatever you see in it”, Miranda replies. “It’s just a composition, a play of colours, nothing more. But I love it.” (3)

Whilst I don’t want to go entirely against the spirit of the point being made here by over-thinking things, the placement of these statements is curious, thrown randomly into the middle of what is arguably one of Franco’s more thematically engaged works.(4) Likewise, it is interesting that, assuming Franco can actually claim responsibility for the dialogue that ended up in the most widely seen German language versions of the films, both ‘Vampyros Lesbos’ and ‘She Killed in Ecstasy’ contain brief passages of considerably more heart-felt and accomplished dialogue than is usually encountered in Jess Franco films (control of the precise words spoken by his characters being an element of filmmaking that was pretty much precluded by the sketchy and dilettante-ish working methods that the director began to embrace shortly after these films were completed).

In terms of additional attractions, Hübler and Schwab’s delirious psyche-rock lounge act is still in full effect on the soundtrack (the fact that its sunny disposition is entirely out of keeping with the maudlin storyline is outweighed for me personally by the fact that it’s just so damn fun to listen to), and I’m pretty sure there’s some distinctive Bruno Nicolai sitar twanging and choral melancholy creeping in here and there too.

Meanwhile, the astonishing La Manzanera buildings near Calpe in Southern Spain, designed by experimental architect Ricardo Bofill, are exploited to their full potential by Franco, beautifully framed in queasy, wide-angle compositions that lend much of the film a beautifully way-out, modernist vibe, similar to that provided by the La Grande-Motte complex in Lorna the Exorcist, whilst that big rock near Alicante (now finally identified thanks to Stephen Thrower’s Murderous Passions as the Penon de Ifach, also in Calpe) makes yet another prominent appearance too. (5)

With all this to play for, it is a shame that SKIE’s potential is to some extent squandered by the obvious haste with which it was produced. Even by Franco standards, the plotting here is wafer-thin, with all attempts to develop (or in some case even name) the characters left entirely to the cast, whilst the film’s ending – in which Mrs Johnson, her mission of revenge completed, apparently decides to immolate herself in a car crash – is so rushed that it gives the impression the movie simply ground to a halt when the final reel of film fell out of the camera; an unsatisfying conclusion to the personal journey that Miranda’s excellent performance has drawn us into over the preceding 70-something minutes, to say the least.

Additionally, viewers unaccustomed to Franco’s, shall we say, ‘emblematic’ approach to special effects may find themselves feeling cheated by the laughable shoddiness of the film’s ‘gore’ effects, in which a thin sliver of stage blood across Vernon’s neck is used to represent a sliced jugular, whilst other acts of violence conveniently take place off-screen. Filming mostly in hotel rooms and borrowed apartments, it’s easy to believe that Franco and his crew were simply worried about making too much of a mess if they started throwing blood around, but, regardless of how indulgent us fans may be of such shortcomings, it’s hard to deny that this approach does put a bit of a damper on the visceral pleasures of Soledad’s murderous rampage.

For all these reasons and more, ‘She Killed in Ecstasy’ is too slap-dash and under-developed to really make the grade as one of Franco’s best films, but I have to admit upon that upon re-visiting it for the first time in a while, nuggets of the director’s personality and unique vision nonetheless shine strongly through its ragged surface. Wedged in between the film’s more obvious failings are passages of meditative reflection, self-conscious pop art excelsis and primal catharsis that, like the more fully formed ‘Vampyros Lesbos’, make it absolutely essential viewing for Francophiles, and a curiously compelling item for anyone with an open-minded interest in marginal and, in its own way, challenging cinema.

------------------------

Kink: 4/5

Creepitude: 2/5

Pulp Thrills: 3/5

Altered States: 2/5

Sight Seeing: 4/5

-------------------------

(1) Vernon gains even more respect for the extent to which he was obviously willing to commit to the warped vision of his good pal Jess. Not only does the venerable actor briefly go full frontal here, he also subsequently appears as a corpse, stretched out naked with an unconvincing gore effect covering his ‘castrated’ genitals – not an indignity many middle-aged veterans of films by Melville and Truffaut would have consented to, one supposes. [Vernon’s admirer’s should note that whilst it appears on the Severin blu-ray edition, this grisly shot appears to have been trimmed from the older UK DVD from which I took my screen-grabs.]

(2) The appearance of the LeCarre book (in English, no less) is a good example of what I take to be Franco’s occasional habit of throwing whatever paperback he happened to be reading at the time into a movie; also see Barbed Wire Dolls and Mil Sexos Tiene La Noche.

(3)If the extent to which Mrs Johnson seems to have prepared for her seduction of Dr Crawford – renting a spacious apartment and developing an elaborate back story as a jet-setting itinerant artist – seems unlikely, well… it is, I suppose. Don’t look at me, I didn’t write the bloody thing.

(4) It addition to SKIE’s possible political dimension, it’s also worth noting in passing that it is the only Franco film I can think of to include a significant amount religious imagery. In addition to the black humor of Professor Walker’s pre-adultery prayers, Franco’s camera lingers extensively over ornate Catholic iconography, both in the flashback to the Johnsons’ wedding, and also during the scene in which she hooks up with Muller’s character during a service at the same church. Barbed commentary on the Church’s collusion with the Generalissimo’s regime, or just a way to make some potentially boring scenes is bit more visually interesting? Your call.

(5) One of the most distinctive locations used in Franco’s ‘70s films, the unmistakable La Manzanera went on to provide the primary location for ‘Countess Perverse’ (1973), along with fleeting appearances elsewhere through the early ‘70s and beyond. Interestingly, both ‘Countess Perverse’ and ‘She Killed in Ecstasy’ go to great lengths to create the illusion that the buildings are located on an island, rather than on the coast of the mainland. For fans out there who enjoying pondering the theory of different Franco films taking place within the same fictional universe, it is fun to speculate that perhaps the villainous Count and Countess Zaroff in the later film moved into the house previously occupied by the Johnsons…?