Friday, 29 May 2015

Krimi Casebook:

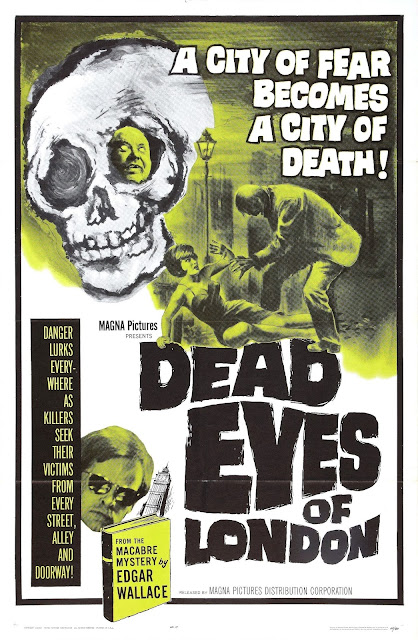

Die Toten Augen von London /

‘The Dead Eyes of London’

(Alfred Vohrer, 1961)

Die Toten Augen von London /

‘The Dead Eyes of London’

(Alfred Vohrer, 1961)

Amid the greasy cobbled streets of a “London” apparently stuck in some strange amalgam of the 1890s, 1920s and 1960s, a visiting Australian wool merchant loses his way in the obligitory peasouper smog. Accosted and beaten by parties unknown, we see him bundled into the back of a sinister white laundry van. “Accidents like this happen every time we have this fog”, remarks the coroner after the corpse is fished out of the Thames the next morning, having to all appearances died a natural death by drowning.

Dashing Inspector Larry Holt of Scotland Yard (Joachim Fuchsberger) is unconvinced by the coroner’s verdict however. “It looks like the blind killers of London are at work again!”, he announces after a torn piece of braille text found in the victim’s pocket is revealed to contain fragments of a threatening message, and the game is afoot in another rousing installment of Rialto Films’ Edgar Wallace ‘Krimi’ series.

Whilst ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ (released in West Germany in March 1961) may not be quite as action-packed as Harald Reinl’s Der Frosch mit der Maske, this first Wallace film by the series’ other key director Alfred Vohrer is nonetheless as an equally impressive achievement. Whilst Reinl’s film cruised by on a sense of pure, pulpy momentum, Reinl’s directorial style is slower and more static, but his trump card here is atmosphere, and, as its title rather demands, ‘The Dead Eyes of London’ (also known as ‘The Dark Eyes of London’) has it in spades.

Apparently owing less to Wallace’s 1924 source novel than to an earlier British movie adaptation from 1939 (with which I’m entirely unfamiliar), ‘Dead Eyes..’ seems, like many Krimis, to fall into that peculiar category of movies that seem to embrace all of the aesthetic trappings of horror film, whilst not actually being horror films.(1)

Certainly, great effort has been taken here to create a feeling of claustrophobic, Jack-the-Ripper-haunted London as rich and indigestible as that of any film ever made in a similar vein. Dark, overhanging streets, canes tapping on cobbled pavements, squalid slums that seem to hide every conceivable variation on grinding poverty and moral degradation, sinister, elongated shadows stretching across each soot-blackened brick wall as misshapen proletarians cringe in fear - you name it, this movie’s got it (well, minus the top hats and horse-drawn coaches at least), all swathed in enough dry ice to put your average Italian gothic moldering in the shade.

Apparently, this particular ‘London’ houses a notorious brethren of blind criminals, who emerge to commit their misdeeds upon foggy nights when, quoth Inspector Larry, “they can more easily take advantage of their victims”. The coldly oppressive atmosphere of the poverty-stricken religious mission from which at least some of these ne’erdowells operate could have come straight from one of Pete Walker’s unsettling ‘70s horrors, and it is within a vast Victorian drainage duct beneath this institution that we find the lair of the film’s chief representative of this loose ensemble of visually-impaired villainy – a hulking, white-eyed ogre named ‘Blind Jack’, as portrayed by an actor (Ady Berber) whom I can only assume was Germany’s equivalent of Tor Johnson or Milton Reid. (Oh, for the days when each national film industry had a gigantic, lumbering brute on call 24/7.)

Although ‘Blind Jack’ provides the closest thing this quasi-horror film has to a monster, handling stalking, stomping, strangling and gurning duties with admirable aplomb, the cynical nature of Krimi plotting of course demands that he and his sightless cohorts are merely pawns in a game beyond their control, as the net of guilt eventually spreads itself far more widely across the film’s more outwardly respectable characters.

It is this side of the story that allows Vohrer to deepen the film’s sense of seedy urban degradation even further, drawing on a well of comic book noir imagery that mix strangely with the quasi-Victoriana of the ‘London’ setting. This feeling hangs particularly heavily over the scenes that take place within the supremely down-market casino / nightclub where many of our gentlemen of ill-repute congregate – a joint where it perpetually seems to be closing time, and the occupants perpetually exhausted; you can almost smell the stale beer and cigar smoke hanging in the air.

It is here, predictably enough, that we’re introduced to the film’s obligatory ‘bad girl’ (Finnish actress Ann Savo), who once again is violently punished for her floozy-ish ways in cheerily misogynistic fashion, assailed by a faceless, black-gloved assassin amid the classic “neon sign outside bedroom window” ambience of her ‘Soho’ bed-sit, in a highly fetishised murder sequence that, whilst not explicitly gory, couldn’t have anticipated the MO of the Italian giallo any more clearly if it had cut to a shot of Mario Bava and Dario Argento crouching outside the window taking notes.(2)

On the side of law and order meanwhile, ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ sees the duo of Fuchsberger and Eddi Arent reunited, but sadly the good feeling that their partnership generated in ‘Fellowship of the Frog’ is rather squandered here. When left to his own devices, Fuchsberger is just fine of course, delivering a mixture of Roger Moore smarm and Stanley Baker-esque determination that makes him the perfect leading man for this kind of movie, but Arent proves more troublesome, having already settled into the persona that he would go on to embody through the majority of his appearances in the Rialto Krimis – namely, that of a comic relief goofball straight from the pits of movie fans’ very own hell.

Whilst ‘Der Frocsh..’ proved that Arent could be a somewhat charming screen presence when gifted with a moderately interesting character to flesh out, here, as Fuchsberger’s perpetually clowning partner, he’s simply a lead weight dragging against the film’s momentum. Veteran comic relief haters in the audience will already feel a shudder down their spines when his character is introduced as ‘Sunny’ (“a nickname that reflects his disposition”), and it’s all downhill from there I’m afraid, as Eddi does his level best to reinforce every unfair stereotype you might have heard about the German sense of humour.

Altogether more pleasing – if equally predictable - is the appearance of a young Klaus Kinski, here essaying the first of a multitude of highly suspicious characters he brought to life whilst on Rialto’s payroll. This time around, Klaus plays a neurotic secretary at a crooked life insurance company, and is just as much of a fidgety, tormented wreck as you might anticipate, sporting gleaming mirror shades in most of his scenes and – dur dur dur! – a pair of black leather driving gloves that his character likes to take on and off all day long, despite exhibiting no particular inclination toward driving.

Naturally, I will refrain from spoiling things by revealing the precise extent to which Kinski’s character is guilty or not guilty of the film’s assorted outrages, but needless to say, I think an aphorism much in the spirit of Chekhov’s gun could well be proposed, stating that if your murder mystery movie features Klaus Kinski skulking around in a pair of Ray-Bans, you probably won’t be needing that ID parade when it comes to fingering the killer, however elaborate his “obvious red herring” alibi may seem.

Inevitably, ‘The Dead Eyes of London’ features it’s fair share of procedural drag in between these assorted highlights, but, as in all the best entries in this series, touches of visual imagination and black humour often are used to liven up duller moments, as exemplified early in the film when a potentially tedious and exposition-heavy visit to the aforementioned life insurance company is livened up by a flick-knife welding blackmailer and some amusing business with a skull-shaped cigarette holder.

Also keeping things interesting meanwhile is an intermittently hair-raising score, as provided by the supremely named Heinz Funk. Though used only sparingly, Herr Funk’s compositions offer a mixture of beat-inflected suspense jazz and dissonant, primitive electronics that sounds somewhat like the result of John Barry and Pierre Boulez getting their demo reels mixed up in one of “London”s dark alleyways.

As a director, Vohrer’s camera tends to remain fairly static, but he does seem to display a love for odd stylistic twists that tend to make his compositions stand out, including a few fun process shots utilising complex arrangements of mirrors and reflections. In what is perhaps the film’s most bizarre moment, Vohrer utilises a truly odd “inside of mouth” shot, complete with giant cardboard teeth in the foreground, to dramatise the entirely unimportant detail of an old geezer spraying his gob with breath freshener prior to leaving the bathroom.

The time and effort taken to create such a weird shot, with no apparent narrative justification, seems entirely inexplicable within the normal working methods of low budget commercial cinema, but its presence does perhaps go some way toward demonstrating the kind of freedom that Rialto’s directors were allowed in this period – a freedom that possibly helps explain why the best of the Krimis stand out as so much more fun and inventive than most of their competitors in the early ‘60s Euro b-movie stakes.

And, insofar as I am qualified to pass judgment at this relatively early stage in my immersion in the genre, ‘Die Toten Augen von London’ would indeed appear to be a truly exemplary example of Krimi style – a creaky, meandering potboiler enlivened, and indeed even twisted into entirely new shapes, by an admirable combination of cinematic craftsmanship, grisly gallows humour and a rogue’s gallery of strikingly memorable character players; the result being an exquisitely sinister time-waster, enriched with enough weird visual fibre to make it a keeper over half a century after everyone should have stopped caring.

----------------------------------------------

(1) Other black & white era examples of the not-quite-horror-film that immediately spring to mind include ‘Tower of London’ (1939), Vincent Price’s break-out picture ‘Dragonwyck’ (1946) and the truly peculiar Charles Laughton vehicle ‘The Strange Door’ (1951), amongst many others.

(2) Whilst it is foolish of course to try to assign any direct chains of influence when dealing with vague and general notions such of these, the this scene in ‘Dead Eyes of London’ could be seen as anticipating Bava’s pivotal ‘Blood & Black Lace’ (1964) on several levels - not only via the aestheticised sadism of the murder and the anonymous, black gloved killer, but even the strobing effect provided by the flickering neon sign outside the window seems a precursor to that film’s antique shop sequence. (If you want to stretch the point even further, could even make the case that a memorable death-by-lift-shaft sequence elsewhere in the film could have provided the inspiration for the conclusion of Argento’s somewhat Krimi-informed ‘Cat O’ Nine Tails’ (1972) as well.)

Saturday, 16 May 2015

Japan Haul:

‘A Funeral For Maya’

by Ichijo Yukari

(1972)

‘A Funeral For Maya’

by Ichijo Yukari

(1972)

For one reason or another, I never really got around to scanning most of the junk shop treasures I brought back from my trips to Japan last year, or indeed sharing any of the photographs I took of astounding, pop culturally significant locales. With another visit now booked in September though, this summer seems a good time to start ‘clearing the decks’ in preparation for whatever random oddities I fill my suitcase with next time.

Within what I am now declaring to be a loosely connected series of posts here, we’ve already breathed in some Yokai Smoke, viddied a few movie brochures, and enjoyed the extraordinary tale of The Devil’s Harp. What better way to continue then than with another manga - this time, another standalone volume with a title that roughly translates as ‘A Funeral For Maya’. The enticing psychedelic cover artwork caught my eye as I was trying to navigate my way around one of the several gigantic manga emporiums in Tokyo’s Nakano Broadway, and 100Y (approx. 60p / 80c) later, a mass of crumbling low-grade paperstock and lavender inking was all mine.

Born in 1949, Ichijo Yukari remains a phenomenally successful creator of shōjo (‘girls’) manga, and it seems she was already a master of her craft at the age of 22, when this supplement to the popular Ribon shōjo magazine was published in July 1972.

Whilst I can’t give you a full plot synopsis, a rough translation of the introduction on the inside cover goes as follows:

“Maya, a girl who lives for hate and never smiles, meets Reina, a beautiful girl, who lights up her heart with love. The invisible thread of destiny connects them to each other…”

Judging by some of the artwork found within, raven-haired Maya would also seem to be somewhat, uh.. spectrally inclined.. apparently appearing out of nowhere as Reina rides her horse through the woods, and a full-on Sapphic kiss between the two mid-way through the story seems daring to say the least. Deliciously horror-tinged, gothic/romantic stuff, I’m sure you’ll agree. A few select scans can be enjoyed below.

(Thanks once again to Satori for translation assistance.)

Labels:

1970s,

comics,

gothic,

Ichijo Yukari,

Japan,

JH,

lesbianism,

manga,

romance

Friday, 8 May 2015

Weird Tales:

The Devil’s Bride

by Seabury Quinn

(Popular Library, 1976 /

originally published 1932)

The Devil’s Bride

by Seabury Quinn

(Popular Library, 1976 /

originally published 1932)

Whilst H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard have proved to be by far the most influential authors whose work found a home in ‘Weird Tales’ magazine during the 1920s and 30s, your chances of finding either of their names emblazoned upon the cover of a random issue from that era are actually fairly slim. Far more likely, the first name you’ll encounter if you’re lucky enough to stumble across a pile of old WTs in some dusty attic is that of the man who could probably have claimed the title of the magazine’s “star writer”, although his work is pretty much entirely forgotten these days – the lugubriously named Seabury Quinn.

So ubiquitous in fact is Quinn’s name within ‘Weird Tales’, and so vague and generic the apparent subjects of his stories, I have sometimes been given to wonder whether he might actually just be a house pseudonym – a suspicion furthered by the fact that he seems to have more or less disappeared into thin air following the magazine’s golden era, his work largely ignored by the cultish fan base who kept the fires burning for Lovecraft, Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch and the rest.(1)

But no – it turns out that Seabury Quinn (1889 - 1969) was indeed a real person, and was even writing under his real name. A Washington DC-born lawyer, journalist and veteran of the First World War whose professional publications included ‘A Syllabus of Mortuary Jurisprudence’ and ‘An Encyclopedic Law Glossary For Funeral Directors and Embalmers’, Quinn contributed a lifetime’s worth of writing and editorial guidance to a variety of journals and trade publications, in addition, needless to say, to voluminous quantities of pulp fiction.

Presumably the main reason Quinn was shunned by the Lovecraft cult is simply that his work belongs to a more prosaic and old fashioned idiom than the blood-curdling fantasies conjured up by his aforementioned contemporaries, but that didn’t stop him being briefly resurrected within soft covers alongside them in the ‘60s and ‘70s, with US publishers Popular Library putting out a series of collections featuring Quinn’s signature character, the irascible French polymath Jules de Grandin, that eventually ran to ten volumes.

Originally serialised in ‘Weird Tales’ between February and July 1932, the novel length ‘The Devil’s Bride’ was by far the most elaborate adventure undertaken by de Grandin and his Watson-esque chronicler Dr. Trowbridge, and, unsurprisingly, it finds our heroes arrayed against the full might of the powers of darkness, taking on a underground cult of international Satanists who, conveniently, are perpetrating many of their outrages from the somewhat unlikely locale of de Grandin’s adopted home town of Harrisonville, New Jersey.

The fictional town of Harrisonville seems to have been the principal venue for all of Jules de Grandin’s excursions into the occult, and I can only assume that this characteristically unnecessary map insert must have been printed in all of Popular Library’s Quinn paperbacks, as it is largely irrelevant to the story being told here, and sadly we don’t get to visit such intriguing locations as the ‘suicide chapel’ or the ‘lonesome swamp’ (every town should have one).

As a character, Jules de Grandin strikes me as a rather dislikable individual. A kind of amalgam of the more obnoxious elements of Hercule Poirot, Sherlock Holmes and Dennis Wheatley’s Duc de Richleau, his distinguishing features include a fondness for peppering his speech with ever more absurd French exclamations (“ah, par la barbe d’un poisson rouge!”, etc) and a tendency to tug at the ends of his moustache with such fury that “he seemed in danger of tearing the skin from his face” (Quinn uses a variation on that description in almost every chapter). He also enjoys speaking of himself in the third person (usually whilst loudly asserting his correctness on some matter or other), and angrily and repeatedly demanding that everyone within earshot stop what they’re doing and listen to him.

Quite why any of the other characters bother to give him the time of day I’m not sure, beyond the fact that, via that singular magic of omniscience granted to heroes of popular fiction, he is indeed always right about everything.

Illustrations by Steve Fabian.

The first thing to get out of the way regarding ‘The Devil’s Bride’ is it’s obvious similarity to a certain other novel in which a rude, aristocratic Frenchman and his friends battle the powers of darkness, published two years after Quinn’s epic saw print. Indeed, the similarities between ‘The Devil’s Bride’ and ‘The Devil Rides Out’ are considerable, and certainly extend far beyond the fact that Hammer’s film of the latter was retitled as ‘The Devil’s Bride’ for its American release.

Of course, we would never resort to crude accusations of plagiarism in these pages, and the fact is, Quinn and Wheatley share a similar authorial voice, and take a similar approach to the production of smoothly-rendered, formally conservative Victorian-via-Edwardian populist melodrama. Admittedly, Quinn’s prose is faster paced, pulpier and more gruesome than Wheatley, but other than that they seem very much ‘on the same page’ aesthetically speaking, and, when faced with knocking out a gripping tale of nefarious Satanist plotting, it is easy to believe that their respective narratives naturally fell along broadly similar lines, with no conscious borrowing in either direction.

As if to hammer home the point vis-a-vis Quinn’s place within the lineage of hoary old romantic adventure fiction represented by Wheatley, ‘The Devil’s Bride’ begins with a visit to the house of Twelvetrees, ancestral seat of Harrisonville’s much-storied Hume family;

“Old David Hume, who dug Twelvetrees’ foundations three centuries ago had planned the room as shrine and temple to his lars familiaris, and to it each succeeding generation of the house had added some memento of itself. The wide bay window at the east was fashioned from the carved poop of a Spanish galleon captured by a buccaneering member of the family. The tiles about the fireplace, which told the story of the fall of man in blue-and-black Dutch delft, were a record of successful trading by another long dead Hume who flourished in the days when Nieuw Amsterdam claimed all the land between the Hudson and the Delaware, and held it from the Swedes till Britain with her lust for empire took it her herself. The carpets on the floor, the books and bric-a-brac on the shelves, each object of virtue within the glass-doored cabinet, had something to relate of Hume adventures on sea or land whether as pirates, patriots, traders or explorers, sworn enemies of law or duly constituted bailiffs of authority.

Adventure ran like ichor in the Hume veins, from David, founder of the family, who came none knew whence with his strange, dark bride and settled on the rising ground beside the Jersey meadows to Roland, last male of the line, who went down in flames and glory when his plane was cut out from its squadron and fell blazing like a meteor to the shell-scarred earth at Neuve Chapelle.”

de Grandin & Trowbridge, we learn shortly thereafter, are visting Twelvetrees to attend the marriage of the Hume family’s sole heiress, Alice. But, midway through the ceremony, attendees are sent into a temporary stupor when a quantity of what de Grandin later identifies as the dread African bulala-gwai powder is blown through the church windows. When they awake, the young bride has vanished!

Who in heaven’s name could be responsible? Well, tipped off by an ancient family heirloom that tradition demanded the bride wear for her nuptials, de Grandin has an immediate answer – SATANISTS! In his usual easy, unassuming manner, he opens the floodgates and lets the exposition flow:

“‘The work of pacifying subject people is one requiring all the white man’s ingenuity, my friend, as your countrymen who have seen service in the Philippines will tell you. In 1922 when French authority was flouted in Arabia, I was dispatched there on a secret mission. Eventually my work took me to Deir-er-Zor, Anah, finally to Bagdad and across British Irak to the Kurdish border. There – no matter in what guise – I penetrated Mount Lalesh and the holy city of the Yezidees.’

‘These Yezidees are a mysterious sect scattered throughout the Orient from Manchuria to the Near East, but strongest on North Arabia, and feared and loathed alike by Christian, Jew, Buddhist, Taoist and Moslem, for they are worshippers of Satan.’

‘Their sacred mountain, Lalesh, stands north of Bagdad on the Kurdish border near Mosul, and on it is their holy and forbidden city which no stranger is allowed to enter, and there they have a temple, raised on terraces hewn from the living rock, in which they pay homage to the image of a serpent as the beguiler of man from pristine innocence. Beneath the temple are gloomy caverns, and there, at dead of night, they perform strange and bloody rites before an idol fashioned like a peacock, whom they call Malek Taos, the viceroy of Shaitan – the Devil – upon earth.’

‘According to the dictates of the Khitab Asward, or Black Scripture, their Mir, or Pope, has brought to him as often as he may desire the fairest daughters of the sect, and these are his to do with as he chooses. When the young virgin is prepared for the sacrifice she dons a silver girdle, like the one we saw on Mademoiselle Alice tonight. I saw one on Mount Lalesh. Its front is hammered silver, set with semi-precious stones of red and yellow – never blue, for blue is heaven’s color, and therefore is cursed among the Yezidees who worship the Arch-Demon. The belt’s back is of leather, sometimes from the skin of a lamb taken untimely from its mother, sometimes of a kid’s skin, but in exceptional cases, when the woman to be offered is of noble birth and notable lineage, it is made of tanned and carefully prepared human skin – a murdered babe’s by preference. Such was the leather of Mademoiselle Alice’s girdle. I recognized it instantly. When one has examined a human hide tanned into leather he cannot forget its feel and texture, my friend.’”

Any questions?

As the opening paragraph of the above extract will no doubt have tipped you off, one thing that Quinn definitely shares with Dennis Wheatley (and, to be fair, with the vast majority of pre-WWII pulp fiction writers) is an attitude of thinly veiled racism and a not even remotely veiled celebration of 19th century colonialism.

Throughout the novel, a band of steadfast, Anglo-Saxon heroes (aided by the occasional decent but dim-witted Italian or Irishman) confront villains of a universally ‘swarthy’ or vaguely ‘Eastern’ character, as the reach of the Satanic conspiracy spreads to incorporate representatives of just about every culture that exists beyond the comforting bulwark of Anglo-American authority. In addition to these dastardly Arabian Yezidees, we’ve got wild African cannibal cults, blood-crazed Hindoo ‘Thags’ (as Quinn terms the Thuggee cult famously eradicated during the British occupation), and even some non-specific Chinamen for good measure.

So, the usual suspects really. But as if that wasn’t bad enough, guess who’s actually pulling the strings? Yes, it’s those godless Russians! Quoth de Grandin’s camrade Inspector Renouard of the French secret service:

“‘Bien non. I did investigate some more, and I found much. I discovered, by example, that the society to which these most unhappy girls belonged was regularly organized, having grand and subordinate lodgers, like Freemasons, with a central body in control of all. Moreover, I did find that at all times and at all places where this strange sect met, there was a Russian in command, or very near the head. Does that mean anything to you? No?

‘Very well then, consider this: last year the Union of the Militant Godless, financed by the Soviet Government, closed four thousand churches in Russia by direct action. Furthermore, still well supplied with funds, they succeeded in doing much missionary work abroad. They promoted all kinds of atheistic societies, principally among young people.’”

[…]

“‘In England only half a year ago a clergyman was unfrocked for having baptized a dog, saying he would make it a good member of the Established Church. We looked this man’s antecedents up and found that he was friendly with some Russians who pose of émigrés – refugees from the Bolshevik repression. Now this man, who has no fortune and no visible means of support, is active every day in preaching radical atheism. He lives, and lives well. Who provides for him? One wonders.’

‘Defections in the clergy of all churches have been numerous of late, and in every instance one or more Russians are found on friendly terms with the apostate man of God.’

‘Non, hear me further,’ we went on as de Grandin was about to speak. ‘The forces of disorder, and of downright evil, are dressing their ranks and massing their shock troops for attack. Far in the East there is the mutter of a distant drum, and from the fastness of other lands the war-drum’s beat is answered.’”

[…]

“‘Our secret agents have been powerless to penetrate the mystery. We only know that many Russians have been sent to enter the forbidden city of the Yezidees: that the Yezidees, who were once poor, are now supplied with large amounts of ready cash; and that their bearing toward their neighbors has suddenly become arrogant.’”

Good grief - covert representatives of an authoritarian Russian state attempting to undermine Western power by sponsoring fanatical religious movements based in remote areas of Iraq and Kurdistan? Who'd have thought it. Kind of depressing when what must have seemed like the wildest of conspiracy theorising in 1932 takes on a rather more pointed emphasis in the 21st century, isn't it?

Interestingly, we also get a hint that a source of subversive anarchy closer to home may have been on Quinn’s mind when he dreamed up his multitudinous Satanic threat:

“‘In Berlin, Paris, London and New York there is a sect which preaches for its gospel ‘Do What Thou Wilt; This Shall Be the Whole of the Law.’ And as the little boy who eats too many bon-bons inevitably achieves a belly-ache, so do the followers of this unbridled license reap destruction ultimately.’”

At this stage of his life, Aleister Crowley had just returned to London after a period allegedly spent infiltrating the left wing intelligentsia in Berlin on behalf of the British government, and, bankrupt as usual, had begun attempting to generate revenue by bringing a series of baseless libel cases against writers and public figures, including a doomed attempt to prosecute the artist Nina Hamnett for accusing him of practicing black magic in her bohemian memoir ‘The Laughing Torso’.(2)

Though one suspects The Great Beast would privately have been absolutely delighted to know his antics were ploughing a certain amount of discord even in minds of stuffy American magazine writers, perhaps the publishers of ‘Weird Tales’ should be grateful they weren’t on the receiving end of a similarly tenuous lawsuit?

‘Weird Tales’, February 1932 - cover painting by C. C. Senf.

Anyway - once the exact nature of the Satanic threat facing our stout-hearted band of heroes in ‘The Devils Bride’ is fully and laboriously established, the novel unfortunately slides into a rather repetitive ‘chase / confront / regroup / repeat’ formula that presumably functioned a lot more effectively in the story’s original serial publication. Despite a series of increasingly far-fetched action set-pieces that include a police raid on a Black Mass, a machine gun battle with a pack of hypnotically controlled white wolves and hand grenades being dropped from cult-piloted aeroplanes, Quinn’s writing remains too staid and clunky to really generate much excitement, even as an appropriately grand finale sees our heroes traveling all the way to Sierra Leone, where they join forces with the British and French colonial forces to intercept the wedding of Alice Hume to the Dark Lord, which is scheduled to take place in a recently excavated roman ampitheatre located deep in the African interior, and guarded, of course, by veritable legions of Satanically affiliated cannibal ‘Leopard Men’.

Ye gods – a bunch of Soviet-sponsored Arab Satanists kicking up a stink in an ancient pagan temple in the heart of darkest Africa! Talk about a WASP’s worst nightmare. Just as well our cadre of stout Anglo-Saxon heroes are on hand with their lewis guns and sabers to teach ‘em a lesson, eh?

Distasteful imperialist rhetoric aside though, this should at least, you’d hope, be a splendid opportunity for some hair-raising pulp adventuring, but again, the story is sadly crippled by a complete lack of threat or suspense, as the good guys succeed in infiltrating the Satanic congress with a minimum of fuss, then just stand around gaping at the naked ladies and sundry other beastliness on display for longer than seems strictly necessary, before calling in the cavalry and, well, killing everyone basically – as they inevitably would, with the combined might of two great European powers at their beck and call, arrayed against villains who are characterised throughout as a mixture of cringing cowards and brain-washed primitives.

‘Weird Tales’ interior illustration for ‘The Devil’s Bride’

by Stephen Fabian – exact issue unknown.

Speaking of naked ladies, another thing worth mentioning about ‘The Devil’s Bride’ is the element of pure, exploitative luridness that often sits rather uncomfortably alongside the straight-laced “for god & country” tone of Quinn’s prose. Of course if there’s one thing fictional Satanists always enjoy, it’s a good floor show, and the “by the way, she was NAKED” clause popular with later paperback horror writers is frequently invoked, but the frequent descriptions of dreadful atrocities being carried out against lily-white female flesh are dwelled upon to an extent that is surprising for the era, described with a painstaking level of detail that can’t help but make the appalled condemnations voiced by our heroes ring a little hollow.

Presumably it was these titillating descriptions of Satanic ceremonies, rather than the stern sermonising about the moral decay and abject evil they represent, that formed the main selling point of Quinn’s story to the ‘Weird Tales’ readership, and indeed, it is only during these segments that his writing really begins to achieve some of the breathless energy found in the best pulp prose;

“A single quick glance told us she was crazed with Aphrodisiacs and the never-pausing rhythm of the drums. With a wild, abandoned gesture she threw back her mop of yellow hair, tossed her arms above her head and, bending nearly double, raced across the sands until she paused a moment by the drummers, her body stretched as though upon a rack as she rose on tiptoe and reached her hands up to the moonless sky.

Then the dance. As thin as nearly fleshless bones could make her, her figure still was slight, rather than emaciated, and as she bent and twisted, writhed and whirled, then stood stock still and rolled her narrow hips and straight, flat abdomen, I felt the hot blood mounting in my cheeks and the pulses beating in my temples in time with the insistent throbbing of the drums. Pose after pose instinct with lecherous promise melted into still more lustful postures as patterns changed their forms upon the lens of a kaleidoscope.”

[…]

“‘B – but –’ I faltered, only to have the words die upon my tongue, for the red priest stepped forward, unsheathing the simitar from the jeweled scabbard at his waist. He tendered it to her, blade foremost, and I winced involuntarily as I saw her take the steel in her bare hand and saw the blood spurt like a ruby dye between her fingers as the razor edge bit through the soft flesh to the bone.

But in her wild delirium she was insensible to pain. The curved sword whirled like darting lightning around her head, circling and flashing in the burning palm-trees’ light. Then -

It all occurred so quickly that I scarcely knew what happened until the act was done. The wildly whirling blade reversed its course, struck inward suddenly and passed across her slender throat, its superfine edge propelled so fiercely by her maddened hand that she was virtually decapitated.

The rhythm of the drums increased, the flying fingers of the drummers increased, the flying fingers of the drummers beating a continuous roar which filled the sultry night like thunder, and the red-robed congregation rose like one individual, bellowing wild approval at the suicide. The dancer tripped and stumbled in her corybantic measure, a spate of ruby lifeblood cataracting down her snow bosom; wheeled round upon her toes a turn or two, then toppled to the sand, her hands and feet and body twitching with a tremor like a jerking victim of St Vitus’ dance.”

And so forth. There’s quite a lot of this sort of thing.

I hope it doesn’t sound as if I’m being too hard on ‘The Devil’s Bride’ in the paragraphs above. Tedious, contrived and morally reprehensible though it may be, it’s nonetheless a good bit of daft, antiquated fun, and taken on its own terms I enjoyed it a great deal.

What still interests me most about it though is the extent to which it manages to tick all the boxes required of what would later be considered an entirely generic contemporary Satanic cult story, despite hitting stands two years prior to the book I’d always assumed set the original blueprint for that particular formula.

Whilst I don’t currently have the depth of knowledge necessary to offer a full overview of this idea’s development within popular culture, I hope that someone out there does, because I’d be genuinely fascinated to learn how it more or less came almost out of nowhere (perhaps influenced by a kneejerk conservative reaction to the emergence of Crowley, The Golden Dawn, Theosophy and so on in the early 20th century?) and went on to carve out such a place for itself in the public imagination that by the time of the regrettable “satanic panic” of the 1980s, there were a lot of people apparently ready to take the real world existence of covert Satanic cults at face value.

Precisely where ‘The Devil’s Bride’ fits in on this timeline I’m not sure, but I suspect it could be a significant milestone. Perhaps the lower reaches of magazine fiction already abounded with red-robed cultists, black candles and civilised suburban covens prior to 1932, but if they did, I can’t come up with any concrete examples right now. Certainly, Quinn not only beats Wheatley to the punch, but also the bizarro cult overseen by Boris Karloff in ‘The Black Cat’ (1933) – my ground zero for non-historical movie devil worshippers unless anyone can tell me otherwise – and of course, he trumps the slightly more sophisticated take on the theme ushered in by Val Lewton’s ‘The Seventh Victim’ by nearly a decade.

At the very least, Quinn can surely claim some credit for establishing the palette of clichés and images that dominate the field of fictional Satanism to this day. Speaking purely to the horror fans out there (and if you’ve read this far and you’re not, god help you), perhaps just pause to consider the sheer amount of enjoyment we’ve taken over the years in watching hooded extras stomping through day-for-night undergrowth with flaming torches, chanting weird faux-Latin mantras, and offer a pagan blessing to ol’ Seabury for his role in laying down the law for such shenanigans.

Portrait of Seabury Quinn by David Prosser,

from the collection 'Is The Devil a Gentleman?'

(Mirage, 1970), scan via Vault of Evil.

-----------------------------------------

(1) To be fair, August Derleth’s Arkham House did put out several volumes of Quinn stories, but we can assume that they didn’t generate anywhere near the same level of enthusiasm accorded to the various other writers whose reputation the publishing house helped maintain.

(2) As was presumably pointed out at the time, Crowley taking umbrage at being accused of practicing black magic seems akin to Adolf Hitler strenuously denying his fascist sympathies, so god only knows what that was all about. Nina Hamnett incidentally was an absolutely fascinating figure in her own right, and it makes me happy to learn, via my usual exacting wiki-research, that she was born and raised very near my own ancestral home, in Tenby, South-West Wales.

Friday, 1 May 2015

Nikkatsu Trailer Theatre # 3:

A DRAGON SYMBOL

ADORNS THEIR HELMETS!

A DRAGON SYMBOL

ADORNS THEIR HELMETS!

Well I don’t know about you readers, but I’m already heading to my local picture house to demand a ticket for Yasuharu Hasebe’s third and final instalment in the Stray Cat Rock franchise, and the fact this is neither 1970 nor Tokyo be damned.

Labels:

1970s,

bikers,

drugs,

Eiji Go,

film,

Japan,

Meiko Kaji,

Nikkatsu,

Tatsuya Fuji,

teens on the rampage,

trailers,

Yasuharu Hasebe

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)