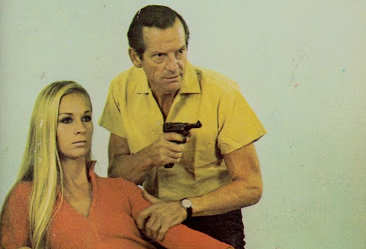

James Fox, Joseph Losey and Harold Pinter on the set of 'The Servant' (1963)

Prior to watching The Damned a couple of months ago, I was entirely unfamiliar with director Joseph Losey (1909 - 1984), and the brief web research I did whilst writing that review mistakenly led me to believe that Losey was a fairly marginal and idiosyncratic figure in mid-century cinema, someone whose wider work was of only passing interest.

It took a pleasantly unexpected email from an employee of the Library of Congress to alert me to the fact that, actually, this is far from the case. Whilst Losey may lack the ‘household name’ status afforded to many of his contemporaries in the auteur business, he actually left behind a prolific body of work, some of it the subject of great critical and public acclaim, some of it derided and mocked by all concerned, and some of it simply too inexplicably strange for the world ever to have passed a coherent judgment. Nonetheless though, most of his films manage to include landmark performances from some of the finest actors of their era, and all of them are stamped with a distinct set of themes and ideas and a recognisable visual style that mark Losey out as a unique and fascinating filmmaker.

My correspondent suggested that I might benefit from investigating a season of Losey’s films being screened by the BFI through June and July, and, embarrassed by my ignorance of the man’s work, I have proceeded to do just that.

As it turns out, the BFI season seems to have been devised as a comprehensive attempt to raise Losey’s standing amongst film fans, and to encourage those of us who might have accidentally caught one or two of his movies here and there to start to view his films as a cohesive body of work. As such, they are/were screening a total of about twenty Losey films, each of them boasting a fascinating plot synopsis, along with incredible cast lists and collaborations with / adaptations from the likes of Harold Pinter, Berthold Brecht, L.P. Hartley and Fritz Lang.

Although I’ve never been a big ‘movie star’ guy and am rarely drawn to a film primarily by the iconic/recognizable faces within, Losey nonetheless seems to have exercised an incredible knack for getting big names (or in many cases, soon-to-be-big names) signed up to his projects, with exciting and sometimes mind-boggling results. If you thought the idea of Oliver Reed as an umbrella-wielding seaside hooligan was pretty cool, wait ‘til you get a load of Robert Shaw and Malcolm McDowell on the run from a fascistic military dictatorship, Stanley Baker seducing Jeanne Morreau in wintertime Venice, Mia Farrow trapped in an incestuous psychodrama with Robert Mitchum, Elizabeth Taylor in a Tennessee Williams adaptation set on a Greek island or Richard Burton essaying the role of Leon Trotsky – all this and much more was promised by the BFI’s programme.

As was set out in brief in my Damned review, Losey began his career in America in the 1940s, gathering a certain amount of praise/notoriety through to the mid-1950s for a series of carefully wrought b-movies such as “The Boy With Green Hair” (1948) and “The Big Night” (1951). The defining event in the establishment of his cinematic style though came via the unwelcome intervention of Joe McCarthy’s HUAC, and the ensuing Hollywood witchhunts. As a man with very real Marxist sympathies that it doesn’t seem he ever tried to hide, Losey naturally found himself blacklisted pretty sharpish. Rather than quietly withdrawing from the movie business or seeking lower ranking work under a pseudonym though, Losey instead made the bold decision to relocate to Europe, his Hollywood track-record presumably helping him gain a foothold within the British film industry, where, he clearly hoped, he would be able to make films without having to compromise his social/political agenda.

Although it took him a few years to find his feet in the UK, Losey seems to have carved a unique niche for himself as a filmmaker from the circumstances he found himself in, establishing an aesthetic that lies somewhere between America and Europe and somewhere between commercial and art cinema, often fusing the best elements of both to great effect. The brooding architecture and opulent furnishings of Old Europe are transformed by Losey’s lens into cavernous textures and claustrophobic framing devices straight out of the playbook of Californian noir, whilst at the same time the tough, b-movie logic of crime thrillers and relationship dramas are used to mercilessly expose the hypocrisy of the British class system and post-imperial capitalism.

And conversely, even in his most commercial and genre-bound work, Losey always manages (or at worst, attempts) to crack open the stereotypes rendered ubiquitous by American film, imbuing his characters with the sort of psychological depths and ambiguous motivations beloved of Truffaut and the Nouvelle Vague, and subsequently the whole of the ‘60s European New Wave, to which Losey clearly felt closer than he did to American film, both geographically and politically. Nonetheless though, his early grounding in the Hollywood studio system means that, unlike many European directors of the ‘60s, entertainment value almost always remains paramount in films, and, furious, unconventional and overtly political though they may be, they rarely cross the line into outright polemic.

Due to time and budgetary constraints, the films I’ve managed to see as part of the Losey season have been a fairly random and scattered selection from his voluminous filmography, but nonetheless, they still represent the most rewarding and varied spate of sustained cinema-going I’ve undertaken in recent years, and I’m looking forward to telling you all about them over the course of the next few posts.

No comments:

Post a Comment